Government responses to Covid-19 will reshape the U.S. economy for the next decade. But why did America’s economy deliver such slow growth during the previous decade, as well as before the 2008 global financial crisis? Why has the U.S. economy consistently generated rising income inequality and sluggish investment for so long? Answering these questions helps establish the baseline for understanding how the Covid shock might change economic structures and outcomes.

Most explanations for slow growth, both before and after the financial crisis, focus on singular causes—like aggregate income inequality, or the rise of a shareholder value model for corporate governance, or increased trade competition (globalization), or the financial sector’s disproportionate power and profitability (financialization). These explanations are important, and in many respects correct. Yet they are also largely incomplete because they ignore the sources of profit, even when they discuss the rising share of profits relative to wages, or of “financial sector” profits relative to “manufacturing sector” profits.

In understanding American capitalism, the origin of—and distributional conflict over—profits matters as much as the distributional conflict between profits and wages. Looking at firms’ profit strategies, and the organizational structures they construct to pursue profit, explains the dynamics and malaise of the U.S. economy.

Put simply, changes in corporate strategy and structure from the postwar era to the current era changed the distribution of profits among and within firms and led directly to our present problems. While the distribution of profits across firms was highly unequal in both eras, changes in corporate strategy and structure have concentrated profits in firms with small labor head counts, a low marginal propensity to invest, and relatively easy tax avoidance. Reduced investment and worsening income inequality in turn slow GDP growth and aggravate social and regional tensions. While these changes are generic to the rich countries, they have gone furthest in the United States. As William Gibson has put it, “The future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed.”

From Fordism to the Information Economy

Broadly speaking, firms in the mass-production era (or as academics like to call it, “Fordism”) sought oligopoly profits by controlling asset-specific physical capital—that is, machinery that could not easily or profitably be redeployed to other uses. This specialized equipment was extraordinarily productive relative to more generic machinery, enabling huge economies of scale. High productivity deterred potential competitors from entering the market, because incumbent firms could easily ramp up production and lower prices, starving potential rivals of profits. Yet with asset-specific physical capital, profitability, to say nothing of profit maximization, required uninterrupted production at near full capacity. Otherwise a firm would have expensive equipment sitting idle and suffer diseconomies of scale. This imperative of uninterrupted production had three important consequences.

First, firms vertically integrated—or brought production of components going into final products in house—to assure a continuous and timely flow of the parts they needed. Even something as simple as a can of soup requires a wide range of inputs. More sophisticated products like the automobiles eponymous of Fordism typically require ten thousand discrete parts. Missing any single part could halt production. After the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, for example, shortages of plastic speedometer needles, among other things, caused car assembly factories worldwide to halt production. As late as the 1970s, GM was making 70 percent of the value of its cars inside its own factories.

Second, as a consequence, these large, vertically integrated firms necessarily had many direct employees. But in-house production of components, and even more so the need to run assembly lines continuously, gave workers a credible threat to firms’ profitability: strikes that interrupted production. Sit-down strikes in the 1930s, legislation legalizing collective bargaining, and a second wave of strikes immediately after World War II produced a temporarily stable bargain. Basically, firms agreed to share oligopoly profits with direct employees if workers ceded control over production to management. The 1950 “Treaty of Detroit” between the UAW and GM exchanged a five-year, no-strike contract for wage hikes in line with average productivity growth and inflation.

Third, big capital investments and big unionized workforces had positive macroeconomic consequences. Gross domestic product is conventionally divided into consumption (including government transfer payments, like Social Security), government spending net of transfers, and investment. GDP growth is thus the growth of any or all of these components. Firms’ high labor head counts combined with unionization to flatten the income distribution, boosting aggregate demand as workers consumed more each year. Firms’ strategic use of large fixed investments in physical capital, which served as a barrier to entry, generated continuous investment. This had strong multiplier effects, again bolstering aggregate demand. Finally, as John Kenneth Galbraith argued in 1967, firms’ desire for stable inputs and demand in largely national markets oriented their political behavior towards seeking macroeconomic stability and predictability.1

Capitalism has winners and losers, though; not all firms succeeded in creating an oligopoly or inserting themselves into the public or corporate planning routines that Galbraith charted. Fordist-era firms thus tended to polarize into two groups: larger, more profitable firms with stable markets, and smaller, less profitable firms in unstable or marginal markets. In a complementary fashion, markets and employers also sorted workers into two groups: largely male, white workers with stable, higher-wage employment in large firms, and largely minority, immigrant, and female workers with unstable, lower-wage employment in smaller, less profitable firms.

Planning, rent sharing, and a dual labor market generated tensions that undid the mass-production era. To be sure, advances in automation and communication technologies enabled some of the changes described below, but the major drivers of change were social and political conflicts in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Compliance with corporate routines and the status quo broke down in a wave of strikes and social movements. Put simply, young workers entering factories rejected mindless production routines and constant assembly line speedup; women rejected confinement to marginal labor markets and marriage; African Americans rejected exclusion from normal American civil and economic life; and newly independent oil producers rejected subservience to giant U.S. and British oil firms.

Strikes and resource price shocks in food and energy disrupted corporate planning, highlighting the vulnerabilities of production strategies that relied on large volumes of fixed, product-specific equipment. Of the two, the strikes were more important in motivating firms to change strategies, and companies began looking for ways to shift labor risks away from themselves and onto to other firms.

From 1964 to 1974, the wage share of value-added per U.S. manufacturing employee rose by 5.9 percentage points.2 Firms responded with public and private strategies to reduce the wage share and regain control over the factory floor. U.S. firms became more politically active in promoting business interests, following a strategy outlined in the 1971 Powell Memo, and in supporting the economic policy agenda embraced by the Republican Party over subsequent decades.3 Privately, firms began to disperse concentrated production and shed legal responsibility for their workers by de-merging, moving production offshore, contracting out (both on- and offshore), dispersing production geographically, and adopting variants of the franchise format.

IBM, for example, shed 40 percent of its workforce between 1990 and 1994, abandoning most manufacturing in favor of R&D, software, and patent licensing.4 Similarly, both GM and Ford spun out their parts production as the independent firms Delphi and Visteon in 1999 and 2000. By 2008, both Delphi and Visteon had more Mexican than American employees.5 Where the old GM had generated 70 percent of final value in house, and Ford 50 percent, almost all automobile firms were down to 20 percent by the 2000s. Contracting out created smaller firms and smaller factories, both of which are harder to unionize. Furthermore, the franchise format removed the legal responsibility to provide benefits and protected an emergent group of highly profitable firms from liability for abuses.

Firms’ new profit strategy sought monopoly profit via control over intellectual property (IP) via intellectual property rights (IPRs), like patent, brand, copyright, and trademark, while ejecting workers and physical capital. IPRs convey an exclusive right to extract value from a given production chain. For example, Qualcomm’s patents on the technologies linking cellphones to cell towers and Wi-Fi enable it to levy a 2 to 5 percent royalty on the average selling price of almost all cellphones.

Unfortunately, to steal a phrase, the more IPRs we come across, the more problems we see. These corporate and political responses transformed the two-tier Fordist economy into a new three-tier economy. Since not all firms can succeed in capturing oligopoly or monopoly profits via IPRs, competition produced three different generic firm types: (1) human-capital-intensive, low-head-count firms whose high profitability stems from robust IPRs; (2) physical-capital-intensive firms whose moderate profitability stems from investment barriers to entry or tacit production knowledge; and (3) labor-intensive, high-head-count firms producing undifferentiated services and commodities with low volumes of profit.

Naturally, some firms blend characteristics of each level. Intel, for example, blends the top two levels of IP ownership and a massive physical capital footprint in its semiconductor fabs.

“Tech” is the obvious epicenter of the new, IPR-based economy. But two caveats matter here. First, IPRs are nothing new. Formal IP was also present in the Fordist era and, indeed, before that. Critically, IP was embedded in large organizations, and generated by the dedicated internal research labs that former RCA Labs engineer Henry Kressel has described.6 Second, many firms outside of tech have pursued an IPR-based strategy. Franchised restaurant chains are the most obvious “low-tech” example, with a high-profit brand owner licensing the use of its brand and production methods to smaller, lower-profit owner-operators in the bottom tier. In both high-tech and low-tech industries, the general pattern is vertical disintegration and the segregation of IP ownership into a small number of legally distinct and highly profitable firms. This largely involves a rearrangement of legal boundaries, not production as such.

The best way to see this is to imagine two different automobile factory tours, one in 1965 and one in 2015. During the 1965 factory tour you would see many different people doing direct and indirect production tasks. The iconic semiskilled workers on the assembly line would loom large. But surrounding them were specialist toolmakers, engineers, designers, janitorial staff, and logistics workers. Farther out—caterers, guards, groundskeepers, accountants, white-collar management, and a second set of logistics workers unloading parts coming from components factories. All these workers were typically legally inside the firm as employees and, white-collar workers aside, union members.

The 2015 tour reveals many of the same kinds of workers—with more racial and gender diversity—doing similar jobs. Automation would have replaced many semiskilled workers, but the logistics personnel, caterers, security, accountants, designers, engineers, and so on remain. The critical differences are largely legal and organizational: where everyone used to be an employee of the core firm, workers doing logistics now might be employees of XPO Logistics, DHL, or UPS; security guards might be employees of Securitas or G4S; caterers might be employees of Aramark or perhaps small local firms. Astoundingly, between 20 and 30 percent of line workers are now typically contracted-in or temporary employees who are technically not employees of the automobile firm, and certainly not unionized. Where firms once did much of the component production in house, they now buy in many parts, some design work, and a considerable volume of the software and electronics (which now constitute about 20 percent of a vehicle’s total cost) from external suppliers. From a production point of view, these essentially legal changes have not impeded increases in productivity. But from a macroeconomic point of view, or with an eye towards income inequality, the shift in the legal boundaries around workers is enormously consequential.

Franchise-based industries provide an even clearer example. Consider the very low-tech world of hotels (online booking is hardly high‑tech, even with web analytics). The major hotel brands neither own physical buildings nor directly employ most of the workers inside. Hilton Worldwide Holdings, for example, is a firm whose major asset is its intellectual property: 5,900 registered trademarks and 15 carefully gradated and curated hotel brands as of December 2018.7 Hilton directly owned or leased only 71 of the 5,685 properties labeled with those brands. The hotel buildings themselves—the middle layer in the new industrial structure—are a large physical asset, variously owned by private equity firms, family trusts, and real estate investment trusts (REITs). For example, a different “Apple”—Apple Hospitality Real Estate Investment Trust—owns 242 hotels in the United States, operating under the nominally competing Hilton and Marriott brands. Apple REIT’s buildings are managed by hotel management firms operating under contract. These management firms either directly employ or contract in labor from third-tier firms like Hospitality Services Group. These jobs can be “gig”-like but are more often standard employment relations. Thus even a low-tech sector like hotels has a tripartite division combining legally separate but functionally integrated firms specializing in IP production, firms holding physical capital, and firms supplying low-skill labor power. Functional integration comes from the tight control that the firms at the top exercise over their franchisees and subcontractors.

This three-tier structure has made firms at the top astoundingly profitable. But it damages the U.S. economy in multiple ways, even before considering the supply chain risks that Covid-19 revealed: First, it skews the distribution of income upward, reducing demand and weakening the state’s fiscal base. Second, and most important, the three-tier structure creates firms with lots of profit but a low marginal propensity to invest, and firms with a high marginal propensity to invest but profits too weak to enable robust productive investment.

Income and Inequality

Income distribution first: U.S. labor law unintentionally combined with rent-seeking in the health care industry to motivate firms to expel as much low-skill, low-value-added labor as possible. The 1974 Employee Retirement Income Security Act (erisa) mandated equivalent benefits for all full-time workers in a firm, and forced firms to account for pensions as explicit liabilities. Health insurance is a flat fixed cost per employee. As health insurance costs rose to the current average level of $20,000 for a family policy, or $7,200 for individuals, they constituted an ever-larger share of the total cost of employment. Health insurance for professional employees might amount to 10 percent of their total cost of employment, but for a $9-per-hour janitor they doubled the total cost to the employer. Far better, in profit terms, to fire the janitor and pay a cleaning service $10 per hour to bring her back in at the same $9 per hour but without health insurance coverage. Generally, the higher a firm’s average wage, the more likely it is that activities like cleaning and catering are outsourced. Gig work for firms like Uber or Instacart is only the most extreme version of pushing workers outside a firm’s legal boundary, removing any obligation to provide benefits.

Second, for a variety of sociological and practical reasons, firms tend to redistribute some of their excess profits inside the firm as wages. Fine-grained studies using anonymized IRS W-2 data have shown that more profitable firms within the same industry tend to pay higher wages for the same job description.8 In other words, it’s not what you do but who you work for that determines your wages—inter-firm rather than intra-firm disparities largely drive wage inequality. Therefore, as profits are concentrated into a small number of firms with low head counts, more and more workers pile up in low‑profit, bottom-tier firms that deliver commodity services or simple manufacturing tasks.

It could be argued that higher-profit firms are more productive because their employees are more productive, and thus that wage differentials reflect differences in workers’ abilities. This is plausibly true for markets like canned soup, where competing products of different qualities are available and easily compared. But the disproportionate profits flowing to finance and to IPR-rich firms reflect various forms of legalized monopoly power. Patents and copyrights are by definition legal monopolies. Likewise, markets in which competition involves a meaningless choice between oligopolistic firms—think cellphone or internet service—also reward firms without regard to underlying productivity. Oligopoly and monopoly (think AT&T) in the Fordist era also concentrated profits, but they were shared over a broader employment base.

The changing relationship between profit shares and employee head count can be seen by looking at the top one hundred publicly listed U.S. firms by cumulative profit in 1961–65 as compared to 2013–17. From 1961 to 1965, sixty-one of the biggest U.S. employers were also among the top hundred firms by cumulative profit, accounting for 41.1 percent of total profits and 38 percent of total employment.9 From 2013 to 2017, only fifty-three of the biggest employers were also among the top one hundred firms by cumulative profit, accounting for 32.6 percent of total profits but only 27.6 percent of total employment. Put differently, in the first era the top hundred firms by profit accounted for 49.8 percent of profits and 42.1 percent of employment, a ratio of 1.18, but in the second they accounted for 49.4 percent of profits and at most 32.1 percent of employment, a ratio of 1.54. More narrowly, IPR-rich firms and finance accounted for 29.8 percent of total profits but only 11.9 percent of all employees, a ratio of 2.50, in 2013–17.

People with more money obviously have more money to spend, but the concentration of income into the top 10 percent of households (by income)—who capture 48 percent of total income—actually hinders the growth of consumption and thus of GDP. Why? As income rises, people typically save a greater and greater proportion of that income, or, as economists would put it, higher-income households have a lower marginal propensity to spend. Because consumption spending accounts for about 70 percent of GDP, rising income concentration slows GDP growth. Buying one South Carolina–built BMW SUV generates fewer jobs and less subsequent consumption than buying three Ohio-built Honda Accords.

A Declining Propensity to Invest

The depression of investment resulting from the concentration of profits into IPR-rich firms and the top financial firms is even more consequential. As with personal income, profits are increasingly concentrated because fewer firms face competition, especially IPR-rich firms. As with high-income households, their marginal propensity to invest is relatively low.

Profits were unequally distributed across publicly listed American firms in both the Fordist and the present eras. The top one hundred listed firms by cumulative profit in the period from 1950 to 1980 captured nearly 45 percent of profits, leaving 55 percent for the remaining 7,759 publicly listed U.S. firms during those years; the top two hundred captured 57 percent. The top hundred firms by cumulative gross profits in the period from 1992 to 2017 captured almost the same 44 percent, leaving 56 percent for the other 16,940 publicly listed firms; the top 200 captured 55 percent of profits. For context, the top 1 percent of U.S. households captured about 22 percent of pretax income from 2013 to 2017; the top 1 percent of listed firms (or 71 companies) captured 44 percent of cumulative gross profit in those years.

Thomas Philippon has charted growing concentration of individual U.S. markets, summarizing and synthesizing considerable other research on the increase in markup power by U.S. firms.10 Jan De Loecker and Jan Eeckhout estimate that the average markup rose from 18 percent to 67 percent for publicly listed firms from 1980 to 2014, with the top 10 percent of firms increasing to a 160 percent markup by 2014. This skewed increase in markup power points directly towards the IPR-rich sectors. According to Goldman Sachs, nine IPR-rich firms accounted for 47 percent of the expansion in margins among the S&P 500 firms through 2018, with Apple alone accounting for 14 percent.11

The shift in profits from the employee- and physical-capital-intensive firms characteristic of Fordism towards top-tier firms characterized by IPRs depresses investment, slowing growth. IPR-rich firms face limited competition, by definition. And while their “investment” does include things like massive server farms and sometimes even production equipment, most of their capital formation is simply paying salaries to people. Brand management is not particularly physical-capital intensive, nor, relatively speaking, is software development. In either case, virtually no capital investment is needed to expand production; the marginal cost of an extra copy of Word or iOS is essentially zero. Like high-income households, high-profit, IPR‑rich firms thus have a low marginal propensity to invest in new productive capacity. (Note that buying existing stocks, bonds, and dwellings is not “new” investment—it simply transfers the money to someone else, who faces the same choice about whether to create growth via new productive investment.)

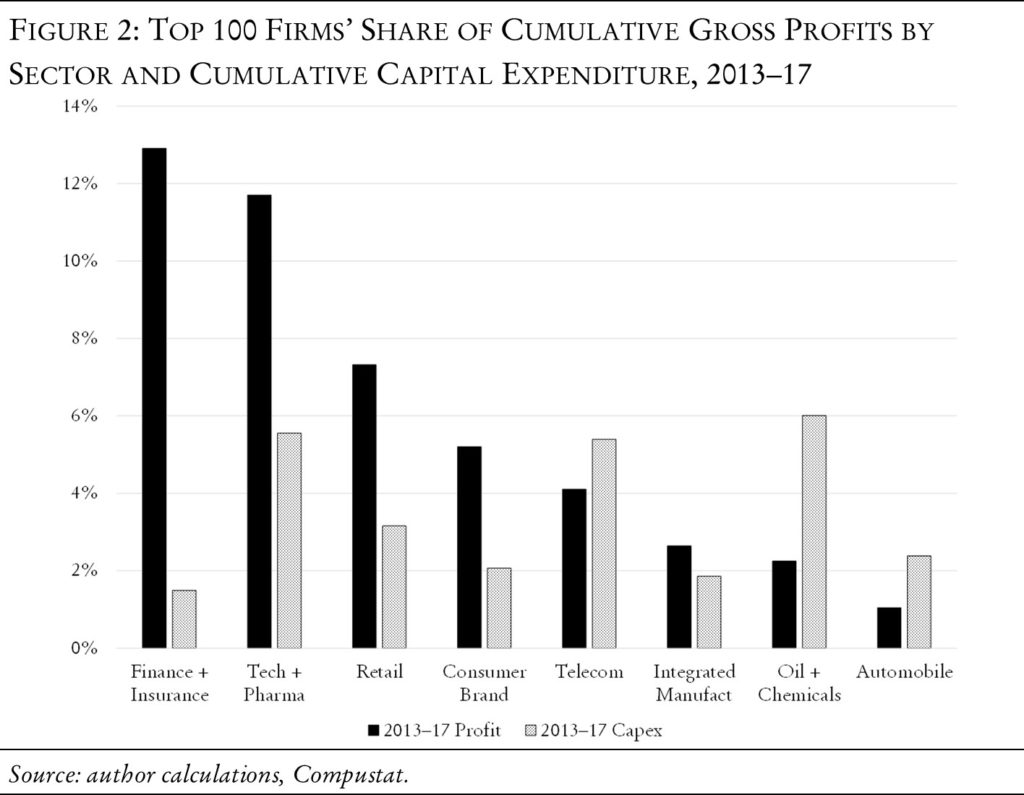

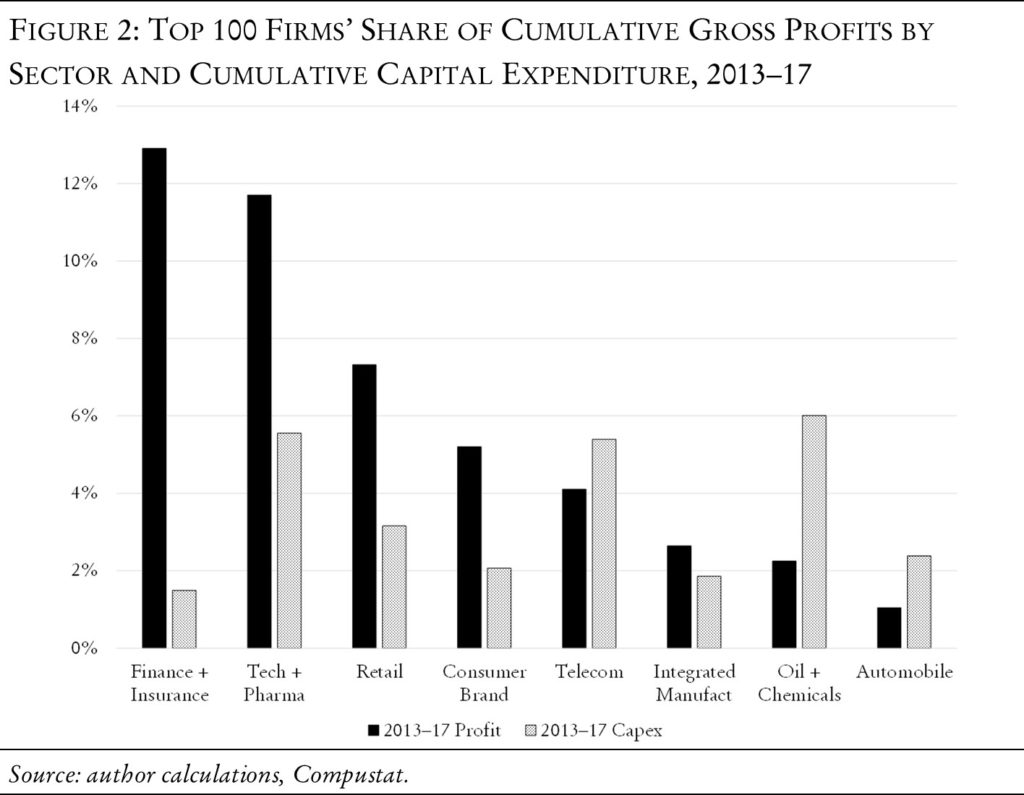

The next two charts show the top one hundred firms’ low marginal propensity to invest by comparing their share of profits (defined as gross operating income) and capital expenditure (which is funded out of gross operating income) in the periods 1961–65 and 2013–17, arguably the high points of Fordism and the current IPR economy. I sort firms into sectors based on their main activity. I also adjust the data by the producer price index to remove any effects from inflation.

I focus on the top hundred firms because of their macroeconomic significance. These firms accounted for 40.5 percent and 34 percent, respectively, of all capital expenditures in each era. This new investment is what drives economic growth in the present and the future. These figures highlight three major changes from the Fordist to the current era: (1) Profits have dramatically shifted towards sectors characterized by robust IPRs, like pharmaceutical, software, and electronics firms, as well as high finance. (2) Even in the context of a general decline in capital expenditure as a percent of gross profit, current high-profit sectors tend to transform much less of their gross profit into capital expenditure. (3) As noted above, the concentration of profits into IPR firms means that firms’ internal redistribution of excess profit now benefits a narrower slice of the working population.

In Figure 1, firms are ranked by their 1961–65 shares of gross profit and capital expenditures. Figure 2 shows the same sector shares in 2013–17. The figures illustrate how the top one hundred firms in the tech, biopharmaceuticals, and finance sectors have replaced telecoms, oil-related industries, and manufacturing as the sectors with the highest profit shares. Yet those new sectors tend to significantly underinvest relative to their profit share.

Figure 2 might seem to contradict the narrative above, as the share of capital expenditure by tech firms relative to the overall economy increases while that of integrated manufacturing firms drops. But while the profit share of tech, pharmaceuticals, and finance has risen sharply, their propensity to reinvest those profits as capital expenditures is very low. By contrast, the manufacturing sector (including the survivors among the old integrated tech firms) continues to invest a relatively large share of its reduced profits.

Overall, capital expenditure as a share of gross profit by the top one hundred firms has fallen by roughly half. Why? While tech firms accounted for 28 percent of business capital expenditure in 2018, according to Goldman Sachs, firms whose profits derive from IPR-based monopolies face less pressure to invest or innovate because competitors are effectively locked out of their markets. Tech and financial firms—and within that group a very small number of firms—simultaneously accounted for 40 percent of 2018 share buybacks, which absolutely exceeded their capital expenditure; combined, buybacks and dividends exceeded capital expenditure plus R&D. But if tech and other IPR sectors underinvest, why doesn’t the money handed out to shareholders produce more investment in other sectors?

The answer is that money doesn’t flow immaculately through financial markets into new investment. Dispersed shareholders typically “invest” by buying up positional goods like expensive real estate or equities whose price has risen because of share buybacks, rather than making productive investments. Meanwhile physical-capital-intensive firms that might do new productive investment with high Keynesian multipliers hesitate to borrow to fund investment. In the context of a slowly growing economy, they quite rationally fear creating excess capacity. Consider the world from their point of view: most developed-country markets in the 2000s were growing at about the rate of population growth, roughly 1 percent per year, and even formerly dynamic sectors like smartphones slowed markedly after 2016. As most manufacturing firms—particularly the big ones in the top hundred or two hundred firms—can generate about 2 to 3 percent productivity growth each year simply through process engineering, the incentive to invest in new capacity is low. Replace depreciated capital to retain market share? Yes. Create new—potentially excess—capacity? No. Indeed, in North America, the automobile industry shed about 15 percent of capacity after 2010 in order to bring supply and demand into rough balance. By contrast, in 2018, Europe’s automobile sector still had roughly 15 percent excess capacity and China’s roughly 25 percent. Similarly, major semiconductor firms—one of the most capital-intensive production processes in the world—moderated investment in the decade after 2010 to avoid excess capacity.

Figures 1 and 2 also show the massive shift towards top firms in the finance sector, and a huge increase in their capital investment. But the bulk of this investment does little to spark economic growth. Much of it is for information technology systems that enable more high-frequency trading or the calculation of deliberately complicated derivatives. Neither does much for the economy—if these investments actually increased productive efficiency, we would expect to see the financial sector’s profits declining as competition and productivity increases operated in the normal way. Instead, these investments produce more economic volatility, as 2008 demonstrated, or generate products with monopoly-like features. Generic, easily copied derivatives make little money. But investment banks increasingly rely on Class 705 business process patents to protect new derivatives and processes. In 2014, for example, Bank of America filed roughly the same number of successful U.S. patents as Novartis, Rolls Royce, or MIT, and J.P. Morgan filed as many as Genentech or Siemens.12 Bespoke derivatives and other forms of rent seeking enable key financial firms to extract rents from nonfinancial firms.

The shift of profits towards firms with a lower propensity to invest did not add up to a Great Depression–style investment collapse before the Covid-19 recession, but it did drive a secular decline in gross and net fixed capital formation that hindered growth. Gross fixed capital formation in the United States fell from 23.2 percent to 20.6 percent of GDP from 1980 to 2017. Net investment drives new growth, but private sector net domestic investment fell from 29.8 percent to 15.6 percent of gross private domestic investment. Meanwhile, IPR-rich firms accumulated immense passive cash hoards. Microsoft, for example, would have been the eleventh largest holder of U.S. Treasury bonds if it were a country in 2019, excluding tax havens; Apple has been described by the Economist magazine as an investment bank that also makes phones.

More Patents, More Problems?

The shift towards a three-tier economy with structural barriers to growth and rising income inequality has created obvious political and social problems. Rising income inequality and barriers to small business entrepreneurship are abstract concepts that conceal declining life expectancy for rural white women, rising death rates from opiates and suicide for white men without college educations, and increasing racial polarization in electoral politics. Even before Covid-19, the U.S. economy and society was shifting towards a nineteenth-century “Victorian” scenario of a one-third, one-third, one-third society, composed of one group of financially secure property owners, one group of workers with reasonably stable employment but no cushion against any serious financial setback, and one group with precarious, often extralegal employment and chronic debt. Read any Dickens novel for details. In Victorian England, racially and religiously marked Irish as well as relatively uneducated rural proletarians populated the bottom layer, much as racial minorities and rural whites disproportionately constitute the U.S. bottom today. But in nineteenth-century Britain, emigration provided a pressure relief valve that today’s United States does not have.

Instead, more and more people are being crowded into the bottom layer of the three-tier economy. Franchises, not iPhones, are actually the characteristic phenomenon of the new economy and its politics. Franchises separate IP and its profits from direct production, shift legal responsibility for workers onto smaller firms with neither the expertise nor inclination to provide benefits or a career path, and decapitate the small business class. While franchising lowers the probability of failure in starting a business, it also removes much of the profit that owners used to capture, and disconnects businesses from their communities. The franchise phenomenon has expanded out of the hospitality niche into many traditional, upwardly mobile blue-collar occupations like home repair, plumbing, and electrical work.

The three-tier model also has malign consequences for U.S. military and economic security. Covid-19 revealed a manufacturing base that was unable to produce even relatively simple things like N95 masks and diagnostic throat swabs in large quantities. This reflected years of shifting the physical work in manufacturing to low-wage Asia. From the point of view of brand and other intellectual property owners, this was an apparently low-risk way to be highly profitable. Let some Taiwanese or Chinese firm deal with the risks of labor unrest and fixed investment in machinery that was vulnerable to a shift in demand. Slap some trademarked swoosh or polo player or athlete’s name on the imported shoe or shirt to justify a double or triple price differential with the generic version, and then park the profit in a sunny tax haven. But the result was an economy that imported nearly all of its shoes and clothing. More significantly, the manufacturing knowledge needed to make large maritime steam turbines has disappeared, and without a massive subsidy offered to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., no one would have built the next generation of semiconductor chip fabrication plants in the United States. Likewise, roughly 80 percent of the raw materials for pharmaceuticals (active pharmaceutical ingredients, or APIs) are imported, as are all generic antibiotics. APIs are the functional equivalent of the bottom layer, as they are combined to make high-profit branded pharmaceuticals protected by patents. The problematic strategic implications of this dependence on China and China-adjacent (in a literal, geographic sense) sources of supply are obvious.

The offshoring of garment assembly, which involves a hard-to-automate process of sewing curves into slippery bits of fabric, was perhaps inevitable. But for many other goods, firms could have taken an alternate route by reengineering their products for automation by using fewer parts and thus less low-skill labor. But this would have made them dependent on higher-skilled U.S. labor and a bigger fixed capital base, with the benefits flowing more to workers and suppliers of automation equipment than the upgrading firm. Instead, U.S. firms and their lobbying groups happily supported trade deals exchanging greater foreign access to U.S. markets (albeit often organized by U.S. firms) for greater U.S. financial access to foreign markets and stronger protection for U.S. IPRs. This produced chronic U.S. trade deficits whose counterpart was an accumulation of U.S. debt overseas. Simplifying greatly, the winners from this were big U.S. retail and financial firms, and manufacturers with recognizable brands, and the losers were the rest of the domestic manufacturing base and its labor force. The winners increasingly parked their profits offshore in tax havens, while the losers drew on an increasingly weak state and federal government fiscal base. All of this makes it harder to transition to the manufacturing of the future, which is likely to involve high-skill workers using flexible automation to make custom products for consumers and industry.

In short, the major economic problem America faces today is not just concentration of profits—which characterizes both the Fordist and current era—but concentration into specific kinds of politically powerful firms subsequent to a legal fissuring of production activities and labor forces. Nothing about the three-tier economy is inevitable or technologically determined. Franchisors’ immunity from obligations to their franchisees’ workers is a domestic legal artifact, as is copyright duration or the robustness and ease of patent protection. Access to cheap offshore labor and tax havens is an internationally negotiated legal artifact. As noted above, the big change is not a wholesale physical reorganization of production processes but rather a wholesale fissuring of the legal containers—firms—that plan those production processes and the creation of a legal architecture supporting the global dispersal of production. In this respect, the fiscal and Federal Reserve responses to the Covid-19 pandemic have already up-ended the old relationship between the state and the economy and opened up space for policy that might ameliorate or reverse the economic problems that the past thirty years of vertical disintegration and offshoring have produced.

Relatively simple solutions that now seem much less politically difficult include higher minimum wages, stronger antitrust enforcement, and more stringent criteria for granting IPRs, as well as shorter terms for such protections. While the $600 per week federal unemployment supplement is unlikely to become a permanent basic income, it not only shows that higher wages and incomes at the bottom are possible but has created a constituency for a permanent expansion. Similar to the wartime experiences driving a federal commitment to health care for veterans, Covid-19 has already exposed the fundamental irrationality of a health care system in which many actors see profits as priority one and patients simply a source of cash flow. Doctors used to constitute a phalanx against federal intrusion, but layoffs and pay cuts at the many practices owned by private equity firms may change attitudes about where the real danger to income and autonomy lie. Finally, forcing lead firms in commodity chains to take some responsibility for workers in the bottom tier would go a long way towards fixing the problems limned above. Similarly, giving franchisees more leeway in the sources of inputs, or making franchisors true risk-sharing partners, would level the playing field in those commodity chains. Right now, franchisors enjoy all the benefits, disclaiming legal responsibility towards franchisees and their workers, while exerting near total control and taking a guaranteed cut of operating revenues. The National Labor Relations Board tried to level that playing field in 2015 in the Browning-Ferris case, but new appointees reversed that decision in 2017.13 Finally, incorporating and actually enforcing labor and environmental standards will help shift production away from China.

Policy proposals of course mean nothing without public support and legislative action. We already have examples of political rhetoric that might move policy in the right direction. On the Republican side, Marco Rubio draws on nineteenth-century British Tory “One Nation” rhetoric and the Catholic social thought embodied in the 1891 papal encyclical on capital and labor, Rerum novarum.14 These approaches aimed at secure property rights for the top third in exchange for dignity at work, a living wage, and social assistance for the bottom two-thirds. On the Democratic side, Elizabeth Warren combines the antitrust focus of early 1900s Progressivism with the New Deal’s emphasis on professional administration and income security. These policies sought social peace both as a means for and an outcome of greater productivity and a bigger economic pie. Neither of these politicians will be a candidate in November 2020, but the election is an opening for reengineering the economy in a direction that promises both faster growth and a more unified society.

This article originally appeared in American Affairs Volume IV, Number 3 (Fall 2020): 3–19.

Notes

1 John Kenneth Galbraith,

The New Industrial State (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1967).

2 Dg ecfin, “Ameco database Series acldo,” European Commission on Economic and Financial Affairs.

3 Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson, Off Center: The Republican Revolution and the Erosion of American Democracy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006).

4 William Lazonick, “Evolution of the New Economy Business Model,” Business and Economic History Online 3 (2005).

5 Thomas Klier and James Rubenstein, Who Really Made Your Car?: Restructuring and Geographic Change in the Auto Industry (Kalamazoo, Mich.: W. E. Upjohn Institute, 2008).

6 Henry Kressel, “Edison’s Legacy: Industrial Laboratories and Innovation,” American Affairs 1, no. 4 (Winter 2017), 115–29.

7 Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc., 2019 Form 10-K; Apple Hospitality REIT Inc., 2019 Form 10-K. Apple REIT has no relationship to Apple Inc.

8 Erling Barth, Alex Bryson, James C. Davis, and Richard Freeman, “It’s Where You Work: Increases in Earnings Dispersion Across Establishments and Individuals in the U.S.,” NBER working paper no. w20447 (Chicago: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2014); Jae Song, David Price, Fatih Guvenen, Nicholas Bloom, and Till von Wachter, “Firming Up Inequality,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 134, no. 1 (February 2019): 1–50.

9 All data on profits, employee head count, and capital expenditure are from WRDS Compustat unless otherwise noted. Compustat only has data on listed firms, but analyses by McKinsey suggest similar levels of concentration among privately held firms. Firms held by private equity typically tend to underinvest—the private equity model is built on stripping out profits—so including them would not change the conclusions presented here.

10 Thomas Philippon, The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2019); Jan De Loecker and Jan Eeckhout, “The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications,” NBER working paper no. w23687 (Chicago: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2017).

11 David Kostin, “Where to Invest Now: 2019 U.S. Equity Outlook,” Goldman Sachs, 2018.

12 U.S. Patent and Trademark Organization, “Patenting by organization, 2014.”

13 Browning-Ferris Industries, 362 NLRB No. 186 (2015).

14 “Common Good Capitalism: An Interview with Marco Rubio,” American Affairs 4, no. 1 (Spring 2020): 3–14.