This article is adapted from the first three chapters of the author’s forthcoming The Ownership Dividend: The Coming Paradigm Shift in the US Stock Market. (Routledge, 2023). The views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of his employer.

The Retreat of Dividends and the Changing Nature of the Stock Market

The history of the U.S. stock market is often explained with colorful anecdotes. There is the gathering of the NYSE founders by a buttonwood tree in lower Manhattan in 1792, Jay Gould cornering stocks in the nineteenth century, shoeshine boys handing out tips in 1929, and Jerry Garcia’s deathbed reaction to the Netscape IPO. Those tales can be important as well as amusing. But other equally significant changes in the stock market happen behind the scenes, without a clever anecdote to illustrate them. The emergence of Modern Portfolio Theory in the 1950s and 1960s is one example. The creation of a practical index fund in 1975 is another. The same is true with the 1982 change in SEC rules that permitted the now ubiquitous share buyback programs. These shifts may not have fit the model of “how to make a million in the next twelve months,” but they ended up involving not millions but trillions of dollars over subsequent decades. This article is about another gradual change in the stock market over the past several decades that has profoundly altered the investment equation for tens of millions of individual as well as institutional investors.

For most of its history, the stock market was based on a presumed, and usually an actual, cash relationship between companies and their owners, particularly for larger, more successful businesses. That is, those enterprises paid dividends to their shareholders. In that regard, the relationship was consistent with what someone with an ownership stake in any successful ongoing business might expect from their holding: their share of the profits after all the operating expenses and capital needs of the venture were met. Despite that history—and contrary to what I consider an axiom of business ownership—dividend-focused stock investing has been receding in popularity for more than three decades. The rise and crash of the fleeting dot-com stocks at the turn of the millennium is not the issue here. In the two decades since, a crop of very successful, highly profitable, abundantly cash-generative, and now mature companies have come to dominate the investment landscape. (Today, there are neo-dot-coms, in the form of SPACs and other profitless shooting stars, but they are a sideshow.) That these companies still do not regularly pay the very people who own them is the heart of the matter. Investors may accept this state of affairs, but they should know that it is historically and financially anomalous.

This unusual arrangement is worth highlighting now because we are almost certainly at a period of transition in regard to the stock market. The forty-year decline in interest rates has come to an end. Interest rates may or may not increase from current levels, but the prospect of continued inflation, upcoming quantitative tightening, and the general end of “easy money” invites a reconsideration of investment frameworks built on decades of declining interest rates. Many market participants are now asking what the stock market (and the broader global economic order) will or ought to look like in this new era. Against the backdrop of these discussions, it is worth reviewing how the market functioned, at least in one very important respect, prior to the current arrangement.

Raising Capital, Earning Profits, Paying Dividends

In the beginning . . . there was the Vereenigde Oost Indische Compagnie or VOC. That’s not actually true. There were earlier joint stock companies, but as a practical matter, the Dutch East India Company was the first recognizable stock traded on the purpose-designed Amsterdam exchange. From that exchange’s launch in 1602 until the mid-twentieth century, investment in a stock like VOC was—in most instances and for most people—all about the dividend that investors could expect to receive. That is not to suggest that money was not made and lost on pure price speculations, frauds, bubbles, struggling enterprises, and all sorts of non-dividend investment decisions and holding experiences. Those non-dividend moments are unavoidable when stocks trade daily and dividend payments or changes are made quarterly or annually. But those headline-dominating moments pale in comparison to the much quieter but vastly greater experience of everyday coupon clipping. From that perspective, it is clear that the dividend paid was the ultimate measure of a stock’s long-term success. If the dividend was paid, that was good. If it was increased, that was better. Over the long term, share prices reflected the trajectory of the dividend, plus or minus sentiment factors that influenced the cash yield that was acceptable to investors. Real returns—those adjusted for inflation—show that the cash dividend received in any given period accounted for much, if not all, of the real return for that period, because inflation and dividend growth would largely offset one another. In addition, for almost all of this period until well into the twentieth century, the dividend was also usually the only public information (beyond the share price) that one might be able to get about a traded company. Income statements and balance sheet information were spotty at best.

For the U.S. market, it is not particularly hard to see the relevance of dividends to stock investing for most of the past two centuries. Make your way to your local library. Review its copy of Moody’s Manual of Corporation Securities, the subsequent Moody’s Analysis of Investments, the long-running Commercial and Financial Chronicle (CFC), and others of their ilk from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and you will observe the same thing. That’s not to mention the more obviously named Moody’s Dividend Record, a publication started in 1930 that continues to this day as the Mergent Annual Dividend Record. Apparently stock dividends were important enough to investors to have their own publications.

During most of modern market history, for companies that were publicly traded, the dividend was sine qua non unless the company was in trouble or very small. Most importantly, from our perspective, is that while all major publicly traded corporations not in distress paid dividends, those cash payments differed from what we are used to seeing. Preferred shares were far more frequently encountered then than they are now, often representing 50 percent or more of a company’s capital stack. As the name suggests, dividends on preferred shares came first, ahead of those paid on common equity. And many companies had both types, preferred equity and common stock, outstanding. They would pay on the preferred and might or might not pay on the common. And they could pay at one rate on the former and a different rate on the latter. This capital structure reflected the boom-and-bust contours of the nineteenth-century business and investment cycle. By the end of the century, investors wanted a de jure guarantee before putting up more capital to companies, especially railroads.

In addition, dividends were quoted quite differently. They were listed as a percent of par value of the stock. The latter was usually $100 per share. In that case, a quoted “6 percent dividend” would equate to $6 per share, often paid semiannually in two $3 increments. Investors considering a purchase had to do the math of the actual yield based on the purchase price. For instance, if the shares in question were then trading at $80, the actual annual yield was 7.5 percent; at $120 per share, the yield was 5 percent. Because a par value of $100 was so common it made it somewhat easier for investors to get a sense of whether a company was trading well (above $100), or not so well (below $100).

Today, enormous tech stocks dominate the investment landscape, representing a cashless or nearly cashless quarter of the U.S. stock market by capitalization. The leading issues of the cash age could not have been more different. Railroads dominated the exchanges throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth. And unlike today’s market leaders, these companies maintained a rigorously cash-based relationship with their owners: they paid dividends. If they wanted to keep investors happy and the capital flowing, they had to. Unlike today’s tech giants, railroads required capital and lots of it. For all the cash put in, investors expected cash in return. As a result, a railroad not paying its preferred dividends was a “busted road.” In contrast, a railroad paying cash on its preferred and its common was a successful one. The CFC’s annual railroads supplement would open each issue by listing the trailing seven years (and later ten years) of dividends for each railroad listed. The railroad section of Moody’s Analyses of Investments even calculated a dividend available per mile of road. Yes, a dividend per mile of railroad! Moody’s stock ratings at the time used a simple formula that included profit coverage of the dividend.

Due to the paucity of standardized data, empirical analysis of the pre‑1929 stock market has been difficult. In recent decades, however, a diligent group of historically oriented finance professors, most recently Edward F. McQuarrie from Santa Clara University, have overseen a herculean effort to systematize the scattered sources for the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. That effort has produced a database of prices and dividends for the period before more reliable and better-known data is available. In the description of the financial archaeology that was involved in getting a clear picture of the early U.S. stock market, it is abundantly clear that dividends were as crucial as share prices for the archaeologists. Indeed, taking an aggregate view of the nineteenth century, a period in which stock prices were often flat for long intervals, reveals that the dividend return constituted much if not all of the total return to investors from stocks for extended periods. The database of Yale’s Robert Shiller makes a similar point. It is aggregate data drawn from a variety of sources, but it shows that dividends mattered, with yields between 4 and 6 percent and payout ratios between 50 and 70 percent for the period when his data begins, in 1871, up until the past few decades. The Compustat database provides granular, company-level data starting in the early 1960s. Through the late 1970s, when the database includes four thousand entries per year, including many smaller, earlier-stage businesses, the dividend paying ratio stays in the 60–70 percent range.

The ubiquity of dividends in all but the most recent period is not to suggest a simplistic black-and-white, dividend-or-no-dividend, on-or-off investing climate. There were numerous other important variables that could influence the nature of dividends and their value as a measure of a company’s success. For instance, the tax environment differed radically. After the introduction of the federal income tax in 1913, dividends were exempt from taxation for decades. For the fifty years following the introduction of dividend income taxation in 1954, the rate varied but was often similar to the levy on normal income. That did have an impact on the academic perception of businesses paying dividends, but seemingly little impact on investor practices, at least until the 1990s, when other factors came into play. A notable irony is that for the past twenty years, starting in 2003, dividends have been taxed at a favorable rate, lower than ordinary income for high earners and similar to the rate for capital gains. So when not taxed at all—the first period—dividends defined the market. When highly taxed—the second period—they were still omnipresent, until the world went topsy turvy in the 1990s. And then when they were less taxed versus the prior decades—the third period—they essentially disappeared and have remained a minor component of our current investing climate. While taxation may be an important factor in the investment equation for many market participants, it does not appear to have been—nor should it be—a structural one in regard to the relationship between owners of companies and the companies themselves.

Stock buybacks offer another telling contrast. Although securities were redeemed and retired as part of the periodic recapitalization of companies, buybacks as a supposed means of “rewarding” company owners made no sense until the most recent decades. For the first two centuries of the U.S. market, companies were raising capital, not retiring it. That stands in stark contrast to the current paradigm that treats buybacks as “normal” and similar to a dividend. More generally, business and macroeconomic conditions were dramatically different. The prior capital-intensive businesses that characterized and dominated America’s economic rise were strikingly unlike the service economy companies that have emerged over the past half century. Ironically, the capital-intensive historical market paid rich dividends, and the less capital-intensive current one largely does not.

I have described the structure of the stock market and investor expectations vis-à-vis dividends from more than a century ago through the 1980s not because I expect a simple return to the past. There is no particular need now for every public company to have preferred shares or to quote dividends relative to the par value of shares. Dividends per mile of railroad is a fascinating idea, but it is not relevant to today’s investors. Those are superficial, time-specific manifestations of an underlying business relationship between investors and companies. This history tour is simply to highlight that all leading companies, and even moderately successful ones, for most of the first two centuries of the U.S. stock market maintained a cash relationship with their owners, necessarily and logically.

The Decline of Dividends

Notwithstanding this history, over the past thirty years, dividends have been pushed to the stock market’s background and have disappeared entirely from parts of the landscape. Shiller’s database, referenced earlier, shows a notable decline during the go-go years of the 1950s and 1960s, and a structural step down in both yield and payout ratios in the 1990s. (I have not included the data from the Covid years of 2020 and 2021, when the market’s yield retreated from its “new normal” of 2 percent to around 1.5 percent.)

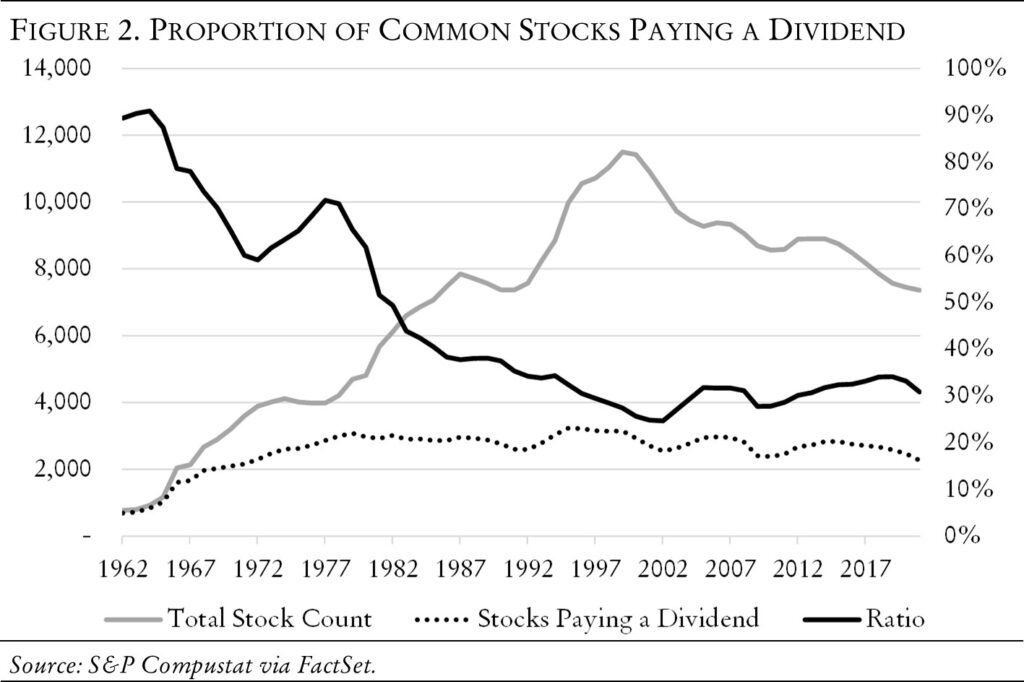

More granular is the company-specific data from Compustat, available from 1962 to the present. Looking at the entire database of holdings, one can clearly see the drop in the number of dividend payers as a percent of overall stocks, to the 30 percent level of recent decades. That is, indeed, a sea change in market structure.

The same Compustat data can be parsed to see the dividend trends at the individual security level. Whatever the metric, it slopes down and to the right. Until the 1990s, dividends mattered. And then they didn’t. As of June 30, 2022, the S&P 500 index had a trailing cash yield of 1.69 percent. That’s nonsensical from a cash investment or business investment perspective, but such nonsense has been tolerated for years by investors and company executives alike. The stock market’s cash yield is now lower than it has been since the modern U.S. stock market started in the early nineteenth century, other than at the very peak of the tech bubble in March 2000. At that time, the S&P 500 index hit a trailing twelve-month yield of 1.1 percent. Even after the most recent sell-off, we are still not very far away from that all-time low number. So, how did we get to the current state of affairs, that is, to a situation in which share prices matter above all else and dividends don’t?

The Academy’s Retreat from Cash

The movement away from a cash-based relationship occurred in parallel in the halls of academe and on the floor of the stock exchange. Before the academics bolted in the second half of the twentieth century, valuation exercises around discounted cash flows and, by extension, dividend payments from publicly traded companies to minority shareholders, were established as the explicit cornerstone of valuation work. Irving Fisher outlined the logic in 1906 (The Nature of Capital and Income), Benjamin Graham explained dividend investing in practical terms in 1934 (Security Analysis), and John Burr Williams worked out the specific math of discounted cash flow valuation in 1938 (The Theory of Investment Value). It’s not at all complicated, and to a great extent, the work done by these individuals was just codifying millennia of actual commerce and investment practice whereby a stream of future payments would be equated in some fashion or another to the market value of an asset. Even if your intention was to sell the asset a week or a month or a year later, the buyer was or should be doing the same mental and actual math: what utility—that is, cash flow—would they derive from long-term ownership?

To this day, it is still an article of faith in academic finance that the proper value of a project or an investment is associated with the net present value of the discounted future cash flows of said project or investment. This approach graces most written valuation work, from a passing reference in academic finance articles to the obligatory cash flow model at the end of equity analyst reports. It is reflected in the acronyms of the trade: DDM, IRR, DCF, NPV. Paths diverge as to the best form or manifestation, and there is a vast array of calculation options. Although this framework has been largely ignored during the past few decades amid the stock market’s “anything goes” environment, it still constitutes the agreed-upon general philosophical framework for business valuation.

This tradition and framework for valuing companies based on distributable and distributed cash flows creates a striking paradox. Despite their embrace of discounted cash flow valuation methodologies, for the past sixty-some years, the leading lights of academic finance have been nearly united in their explicit rejection of the most straightforward manifestation of a discounted cash flow approach for minority shareholders of publicly traded equities. That is, they dismiss the lowly dividend, the income stream reserved for none-too-bright retail investors, for widows and orphans, and other lesser souls. I’m not suggesting that the entire finance community shares this view—there is a dedicated resistance—but among the academic views that make it from gown to town, that are broadly disseminated and recognized in the practitioner community, the consensus is dismissive of companies paying dividends and investors seeking them out.

The formal intellectual history of this movement away from dividends is well-known. It is, in fact, so well-known that I believe many investors simply cite the founding document, from 1961, but don’t actually read it, or haven’t read it in years. That document is worth reviewing closely. A small portion of it remains relevant. The rest of it is so woefully out-of-date as to now meet the standard of being wrong. The long-deceased authors received Nobel Prizes for their efforts and have privileged positions in the pantheon of academic finance. Merely suggesting that this particular work might no longer be relevant invites ridicule from the academy.

Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller (popularly known as M&M) made what was then and still is a commonsense argument in 1958 that the value of a firm should be based on its assets and earnings potential, not on how the entity is financed or the precise nature of its capital structure. They put forth the important concept that the capital structure of a firm should—all other things (including taxes) being equal—be considered irrelevant to the market value of a business. Three years later, in the Journal of Finance, M&M extended their argument from the “front end” of the horse—a company’s capital structure—to the business end, the company’s distributions and returns. Consistent with the increasing focus on share prices, they asked, “is there an optimum [dividend] payout ratio or range of ratios that maximizes the current worth of the shares?” That is, does a higher payout ratio lead to higher share prices?

Their subsequent argument is redolent with the rational actor and perfect markets theories popular at the time, but the key assertion is that “the higher the dividend payout in any period, the more new capital that must be raised from external sources to maintain any desired level of investment.” M&M therefore concluded that a company’s dividend policy is irrelevant because higher payouts necessarily lead to dilutive capital raising, assuming a given level of capital expenditure by the company. Lower payouts lead to less dilutive capital raising. Hence, a company’s dividend payout policy should be irrelevant to the price of a share. Their conclusion creates a rather elegant symmetry of irrelevance involving the capital structure going in, and the distributions coming out.

Did you catch the mistake? It is hiding there in plain sight. Hint: in 1961, it probably wasn’t a mistake, but it is a huge one today, and one that more or less reverses the authors’ conclusions for today’s corporate managers and investors. The key phrase is “for a given level of investment.” And you will note the critical assumption that the given level of investment involved is invariably greater than the cash flow from operations minus the dividend, and thus requires external capital—more if the payout ratio is higher, less if the payout ratio is lower. That’s the rub. In the early 1960s, the United States was still in the heyday of its industrial and manufacturing economy. All that “property, plant, and equipment” came at a cash cost. As a result, dividend payout ratios were high. In this context, M&M made sense. Fast forward sixty years, however, and M&M’s base case is no longer applicable. Our leading service economy companies are now cash flow positive, with much lower capital intensity. It is true that a small subset of the market (utilities, REITs, and a handful of industrials and others at the bottom of their business cycle) remains in M&M territory. On an ongoing basis, it is perhaps 10 percent of the S&P 500 index; it can’t be much more. We are now a service economy in which the overwhelming majority of S&P 500 companies can fund their growth plans without raising external capital. They thereby fall outside the M&M dividend irrelevancy framework. At the aggregate level, the top five hundred companies in the U.S. market have been in that state since the early 1990s, with only 2001 and 2008—periods of crisis—as exceptions.

In their original argument, M&M presciently acknowledged a scenario in which they would be wrong: they admitted that for internally financed companies—which they call an “extreme” or “special” case—“dividend policy is indistinguishable from investment policy; and there is an optimal investment policy which does in general depend on the rate of return.” M&M do not like the analytical implications of this scenario at all. They go so far as to call it “treacherous.” In other words, what was once dismissed with some degree of contempt now applies to the vast majority of the U.S. stock market landscape.

As a side note, it is worth noting that companies repurchasing their own shares were not a prominent feature of the stock market at the time, so it is not unusual that M&M did not fully integrate buybacks into their analysis. Since the 1990s, however, buybacks have come to dominate the stock market landscape. When buybacks are financed from debt, the original 1958 M&M propositions would apply, as it just represents a recapitalizing of a company with a different mix of debt and equity. If the share repurchases are financed from retained earnings, however, then we have the same flaw that the original 1961 M&M propositions have: the dividend or buyback policy counts as an alternative to an investment decision. It may be good, bad, or neutral, but it cannot be irrelevant.

It is critically important to step back from the details and acknowledge the difference between what M&M wrote sixty years ago and how their article is used by market participants in the present. Today, M&M is mostly just a shorthand for the general dismissal of dividend payments by corporations—often in favor of share buybacks—and the general dismissal of cash-paying business ownership by stock investors in favor of finding the next nasdaq darling. But M&M didn’t say that dividends were irrelevant. They said that, under their extremely narrow conditions, dividend payout ratios should be irrelevant to the overall value of the firm. That is a specific finance claim, not a generalized disregard for dividend payments. My point is that it is not what M&M said; it’s what people now think they said. There’s a big difference.

That is not the main flaw, however, of M&M’s dividend irrelevancy theorem. The real issue is equating a harvested capital gain to a dividend payment. Mathematically, the two are identical; that’s the view from academic finance. Money is fungible, particularly in academic exercises involving “perfect” markets. In 1961, M&M treated the matter casually: “investors always prefer more wealth to less and are indifferent as to whether a given increment to their wealth takes the form of cash payments or an increase in the market value of their holdings of shares.” Almost all subsequent academic writing on the topic agrees with that assertion, either explicitly or implicitly, by trying to prove which approach leads to a greater total return. From a business ownership perspective, however, they are not the same, not even remotely in the same league. And the logic of business ownership, particularly for minority shareholders of publicly traded companies, makes a cash distribution from profits—not going into the marketplace to harvest potential capital gains—the most natural mechanism for sharing in the success of an enterprise. A dollar may be fungible; how it is generated is not.

The academic conflation of the two forms of return continued fifteen years after M&M when, in 1976, MIT professor Fischer Black pondered why dividends existed at all. In a brief essay in the Journal of Portfolio Management, Black admitted that he was not able to figure out why companies paid dividends or why investors sought them out. It was, for him, “a puzzle, with pieces that just don’t fit together.” After rehashing the basic M&M propositions, Black listed ways for companies to return cash to shareholders other than dividends. The most obvious was share buybacks, which were not as fashionable then as they would become. His main argument against dividends, however, involved taxes. At that time, they were higher on dividends than on capital gains, and harvesting capital gains can be timed by the shareholder, while dividends cannot. And from a corporate tax perspective, dividend payments are not deductible, unlike interest payments on bonds. Black sums up the problem: “With taxes, investors and corporations are no longer indifferent to the level of dividends. They prefer smaller dividends or no dividends at all.” Like M&M, Black acknowledges that companies with investment programs below their operating cash flow (he uses different words) might have reason to a pay a dividend. And like M&M fifteen years earlier, Black considers these to be “special cases” that are “relatively rare.”

Fourteen years later, in 1990, Black reiterated his view in a brief statement in the Financial Analysts Journal. With a flourish, he ended by forecasting that “taxable [dividends] will gradually vanish.” Black’s line of thought came to dominate the academic narrative about, or shall we say against, dividend payments. Assistant professor after assistant professor has tried to figure out “The Puzzle,” as famed financial journalist Peter Bernstein titled his 1996 contribution to the argument. Bernstein sided with academic finance in writing that “money is money, whether we dress it up in the costume of income or the costume of principal,” and he ends, as Black does, without an explanation for the persistence of dividends.

The academic narrative against dividends has evolved over the years. In recent decades, the initial orthodox finance approach, where the tax differential loomed large, has given way to a behavioral finance framework. But in many ways, the behavioral finance take on dividend investing is just the flip side of the prior approach. Rather than assuming investors are consistently rational and all-knowing (and should avoid dividends for the previously relevant tax reasons), the behavioralists highlight “the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to” when it comes to investing. Instead of being perfect at decision-making, it turns out that we are often biased, which makes us rather bad at it. From this perspective, investing for dividends is a “fallacy,” a deficiency that is typical of investors who make a myriad of little but important mistakes. A recent summary of the academic literature in the Journal of Finance concluded that retail investors are “more naïve . . . [in regard to dividends] than academic finance has generally assumed.” Try as they might, the most visible and vocal finance professors still cannot find a logic to the most natural and logical form of rewarding minority-stake investments.

Causes of the Market’s Move away from Cash

The academics set the stage for the dramatic transformation of the relationship between corporations and shareholders in the U.S. stock market, but the professors did not make it happen. The market structure changed for different, more profound reasons. The first and most important is the drop in interest rates that occurred from 1981 until 2021. The second is the seemingly innocuous and minor securities law change in 1982 that permitted share buybacks. The third is the rise and indisputable success of Silicon Valley and the resulting shift in capital allocation. The tax reason, so aggressively purported and promoted by academics over many decades, does not figure in this process, as the tax differential is now much less than it was when dividends were more prominent.

Interest rates. Asserting that the decline in interest rates has had an outsized impact on the stock market will ruffle no feathers. Everyone can agree on that. My purpose is simply to connect it to the dividend drought in the U.S. stock market. Falling rates affect the mechanics of the market in two ways. The first is straightforward: rates of interest on government securities set the competitive floor for the yield of all financial instruments. As government rates rise, other private-sector bonds need to offer a competitive yield to find buyers. As they fall, bonds can pay less and still find customers. The dynamic is similar though not identical for equities. Prior to the 1990s, most stocks had dividends and their attractiveness was judged, at least partially, by their yield. So, not entirely unlike bonds, as the yield on government securities moved up or down, the cash return expected from stocks would adjust as well. Even today, in the “post”-dividend market, I have been frequently told by company management teams, particularly around spin-offs or mergers of old economy companies where a dividend already exists or is expected, that they are planning on setting the new entity’s dividend so that it will have an “attractive” yield. I am always bemused when I hear that, as it suggests the executives can control stock prices and therefore determine stock yields. While that is not actually the case, up until the 1990s, investors genuinely did care about the cash yield of stocks. So, just like bonds, as the yield of the U.S. ten-year note came down, the necessity for stocks to offer high, competitive, cash dividend yields diminished over time.

Setting the floor for competitive cash rates may be less important than the role of rates in determining risk. As benchmark rates have come down, so too has the discount rate applied to present and prospective cash flows. The four-decade trend toward lower rates has created an almost anything-goes environment in the stock market. Persistently lower discount rates translate into persistently higher valuations. The declining rate trend goes beyond just the high valuation of cash flows or income streams that is reflected in the S&P 500 index’s low dividend yield. It also supports the normalization of entirely dividend-free stocks, including from large successful companies that could afford and ought to pay dividends. Without a distributable cash stream, the investor in a successful enterprise is entirely dependent on the ever-changing market price of the investment. That is the dictionary definition of speculation. Declining interest rates have expanded the scope for such companies. As of the end of 2021, a stunning 111 companies, representing 25.3 percent of the S&P 500 index by market cap, make no distribution. Recall that these are the best of the best—the largest and most successful listed U.S. corporations. They are not start-ups. Even if they are cyclical and at the bottom of a particular business cycle, they are presumed to be durable. Otherwise, they would not be part of the leading stock market index. At any given point in time, some portion of them might reasonably be expected to suspend a dividend due to near-term distress, but not 20 percent of them. Another seventy-nine companies, with 26 percent of the index’s value, trade with a yield of less than 1 percent. In sum, more than half the S&P 500 index by market cap is dividend-free or so dividend-light that it might as well be dividend-free. That is a stunning state of affairs and a real challenge to any investor seeking to establish a typical, cash-based ownership relationship with investments through the stock market.

Share buybacks. Share buybacks did not cause the dividend retreat, but they quickly rushed in to fill the void left by cash payments to company owners. In doing so, they have changed the math of investing in the stock market. During most of the modern era of stock market regulation following the Great Depression, buybacks were few and far between as executives sought to avoid drawing the attention of the SEC, which was concerned about share price manipulation. Loosening the restrictions was considered in 1967, 1970, and 1973, but only finally occurred with the promulgation of SEC rule 10b-18 in 1982. That rule permitted companies to engage in open-market purchases of their stock as long as they followed a set of stated guidelines designed to make the process somewhat transparent and less likely to move share prices around.

By the late 1990s, the dollar value of buybacks by S&P 500 index companies exceeded those of dividends, and that has remained the case in all but a handful of years since. Buybacks are now a highly visible and important component of the current stock market paradigm.

From a business ownership perspective, buybacks change the ownership calculation, for both the investor and for corporate management. First, buybacks are popular because they are believed—by management and some investors—to lead to higher share prices by virtue of introducing an additional motivated buyer. Second, buybacks demonstrably lift near-term EPS by lowering the denominator in the profit-per-share calculation. This benefit depends greatly on whether the funds used are from profits earned or dollars borrowed, and the extent to which the denominator needle is actually moved. However achieved, higher EPS leads to higher compensation for senior managers and higher share prices for investors, assuming valuation multiples are maintained. Moreover, buybacks cleanse management stock-based compensation from balance sheets, especially important for nasdaq companies, which typically feature heavy share and option grants. As a result, buybacks introduce questionable short-term incentives for managers and potential conflicts with company owners. Finally, buyback proponents point to the “downstream” benefits for non-selling shareholders—they get a larger share of the remaining corporate pie, including larger dividends and a greater weight in corporate governance. Fourth, buybacks are supposed to be tax efficient in that, compared to a fixed schedule of taxable dividend payments, buybacks can be timed, both by corporations and investors choosing to surrender (sell) their shares, as investors only pay capital gains taxes upon selling their shares. Finally, buybacks (along with dividends) are seen as a corporate signaling tool of better times ahead.

These are the supposed virtues. The reality is much more complicated, far more so than calculating the benefit of a dividend payment. There is no clear evidence that buybacks lead to higher share prices over the long term. Buybacks in a market trending up look good; buybacks prior to a correction look wasteful. The positive EPS effect is well documented; the question is whether the documented reduction in the denominator is anywhere as great as the announcements of these programs often suggest. And then there is a dark side to repurchases, which many companies may learn the hard way in the years to come. Share repurchases financed from debt have been popular as interest rates have fallen over the decades. Indeed, the math of corporations borrowing cheaply to buy back their own shares can appear irresistible. With rates no longer declining, however, it’s not clear that that benefit will remain.

More insidiously, the rise of buybacks has contributed greatly to the shift in the definition of market success from a distributions-based model—the dividends paid—to a nearly exclusive focus on the share price. It also redefines a company’s relationship to the capital markets. Rather than having the capital markets reflect the value of the company—the collective wisdom of investors—share repurchase programs turn companies into market participants, and for several years companies repurchasing shares have been the largest single source of demand. That is above and beyond their supposed core competence of widget making. There may be nothing wrong with that, but investors should be aware of how the investment process—the supposed valuation mechanism of the stock market—has been altered in the process.

Other critics have pointed out that buybacks further the “financialization” of the capital markets by changing the investment optics of a company without actually changing its productive capacity. In a way, these modern critics are repeating the excellent point made by M&M sixty years ago: that a business’s earnings potential, not how the assets are packaged, should drive its market valuation. Buybacks challenge that bit of common sense. For brokerages, hedge funds, and speculators, these new optics are wonderful developments; for investors seeking to benefit from the ownership dividend, buybacks simply muddy the waters.

The rise of nasdaq. The nasdaq exchange started in the early 1970s as a computerized means of showing bid and offer prices among dealers for shares not listed on the major exchanges. Transactions still occurred over the phone, person to person. That would soon change as nasdaq evolved into the widely used trading system we know today. Nasdaq now has around three thousand listings, more than the older NYSE. The market value (as of December 31, 2021) of the listed shares on nasdaq is around $26 trillion, nearly as much as the NYSE’s $30 trillion. More importantly, nasdaq has passed into our investment culture and reality as an entire investment type: innovative technology-oriented enterprises, many located in the Bay Area of Northern California. These Silicon Valley companies have changed the world, full stop. We all know the names: Amazon, Apple, Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Cisco, Amgen, etc. For the past fifty years, these companies had their initial public offerings and raised additional capital, if needed, overwhelmingly on the nasdaq. In doing so, they have changed not only modern life, but also the stock market itself.

Whereas the payment of dividends was the sine qua non of success for companies on the NYSE, it is the opposite for those listed on nasdaq, where dividends are an infrequent occurrence. Of the top five hundred companies on the exchange as of December 31, 2021, only 193 (less than 40 percent) paid a dividend at all. The smallest of these five hundred companies has a market capitalization of $4 billion, so they are by no means insignificant, troubled enterprises. With more than half the data set not having a dividend, the median yield is zero, of course. And when weighted by market cap, the yield of the top five hundred nasdaq companies was just 0.6 percent. Why bother?

There are any number of reasonable explanations as to why nasdaq is essentially a dividend-free zone. Its initial heritage—the place for rapidly growing technology companies with full investment agendas—is certainly the leading one. That would explain why the younger, less established companies appearing on the nasdaq would naturally eschew dividends in favor of investing every spare dollar they have. Of the largest five hundred companies on the exchange, 139 reported losing money in 2021, and a total of 181 had free cash flow of less than $100 million. It might or might not be reasonable to expect a dividend from them. These companies, however, are the exception to the nasdaq rule. The larger nasdaq listings—the top three hundred or so—are, by definition, tremendously successful, and yet they continue to avoid rewarding company owners with cash. Of course, to some extent they do not need to, as investors are willing to take their chips in the form of abundant capital gains—not withstanding one bubble and collapse in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and possibly a second one in 2022.

There are other factors as well. I wonder if distance from New York and “old finance” isn’t one of them. Timing most certainly is. Nasdaq came of age in the 1980s and 1990s, by which time M&M’s “dividend irrelevance” of 1961 had morphed into a free pass to ignore dividends no matter how large and successful an enterprise was. Nasdaq’s later start also allowed its constituent members to be incorporated into Modern Portfolio Theory, which focused so much on share price covariances and so little on dividend payments.

Big Tech is now under siege from the Left and the Right for having become too powerful, too successful, and too dominant. That is not the issue here. The issue is how the emergence of a coterie of large, successful, cash flow–generating companies has changed the investing equation in the United States. Let’s return to the top five hundred nasdaq issues, the best of the best. More than 60 percent have free cash flow of greater than $100 million. Of those companies—all of which can and should be paying cash to company owners—only about half (164) do. And the dividend payout ratio (of net income) for those distributions is just 28 percent. They could do a lot more. For all its virtues, the nasdaq revolution over the past four decades has helped drain the stock market of its cash payments. Without questioning the Silicon Valley innovation engine, I do assert that its success is certainly not due to holding back profit distributions to company owners once the enterprises had grown to size and scale. There is little evidence to suggest otherwise. So much of nasdaq is outside the bounds of M&M that not paying a dividend is a choice, not a necessity.

The Consequences of the Dividend Drought

The collective impact of falling rates, rising share buybacks, and the great success of Silicon Valley has transformed the nature of investment and business ownership throughout the U.S. stock market. The process occurred gradually. Decades ago, investors were put into a pot of the then room-temperature water of the market. Had they been presented with the zero-dividend option, it would have been a shock to them, and they would have jumped from the pot as quickly as a frog. But over the years, the temperature has risen steadily, and investors have stayed, until they are now used to stocks—even large, highly successful, highly profitable enterprises—with no or de minimis dividends. Rather ironically, when the economy was growing faster and needed more capital, companies paid big dividends, but when the economy’s expansion has slowed and needs less capital, it pays almost no dividends. That unusual outcome has changed the stock market equation for most investors.

All but a small band of investors now look almost entirely to share price gains as a measure of their stock market success, not the cash distributions they receive from their ownership stakes. While there is nothing inherently wrong with that measurement tool, investors should appreciate how different it is from the measure of success in private business, or earlier iterations of the stock market. Time horizons have also been shortened. There have always been short-term speculators playing at the casino to make a “quick buck.” All markets are such. But dividend-focused investing is, by definition, longer-term in nature. A single dividend payment has modest value. It is the belief that decades of similar or higher payments are to come that makes the asset worth purchasing. Assets stripped of such payments leave investors entirely dependent on share price movements alone, and those can occur in days and weeks, rather than years.

The same logic applies to company managers. Long-term cash flows come from long-term investments. Knowing that investors expect to receive the excess cash flows of an enterprise for years to come pushes corporate managers—it is assumed—to make decisions that pay off over an extended period, not just in the quarter ahead. While dividend payments can compete with capital that could be reinvested, both are long-duration financial commitments that, to a great extent, complement one another. In that sense—counterintuitive as it may seem—a dividend obligation should encourage long-term investment. A real-time example is Intel. It is facing a nearly $90 billion incremental investment program over the next decade as it tries to catch up with its peers after years of outsourcing and skimping on investment. To some extent, Intel is a poster child for American industry in the neoliberal period. Now facing a new set of geopolitical realities, Intel needs to catch up. The chip giant generates around $30–$35 billion per year in cash flow from operations. Normal capital expenditures have run at $15–20 billion annually the past few years, leaving plenty of cash for the $6 billion dividend commitment. The rest has been spent on share repurchases that amounted to $14 billion in 2019 and 2020. Intel’s new guidance has been for much greater investment over the next five years and “significantly” lower buybacks. In that context, the dividend commitment is relatively minor and is a way of keeping faith with long-term owners while the company “builds back better.” As of June 30, Intel yields nearly 4 percent.

Dividend payments also dampen total return volatility of individual investments because a portion of a stock’s annual total return appears steadily and more or less predictably. The absence of those regular payments leaves investors entirely dependent on the whims of the market and other investors. For many investors, that roller-coaster ride has worked just fine, especially when the chart line is up and to the right, as it has been for most of the past thirty years. There are times, however, such as the first half of 2022, when the chart is downward sloping, quite sharply for many of the darlings of the prior five years. This is not to suggest that dividend-paying stocks can’t sell off dramatically, but the nonpaying companies do seem more prone to hitting big air pockets. Traders and hedge funds will prefer the wild ride of the market darlings. Business owners and long-term investors should, all other factors held equal, prefer the coupon-clipping, coupon-growing experience of strong dividend payers.

The prior cash-based market also used to provide a vetting mechanism. By contrast, with no cash obligation to investors, it is much easier to cash out venture capital chips through an IPO than it probably ought to be. Critics will object that the stock market is precisely the right platform for investors to take risk and allocate capital to emerging companies. I have no disagreement there, though the venture capital world has done most of the entrepreneurial heavy lifting the past few decades. The issue for investors in the public markets is helping them distinguish between larger, cash flow–generative companies and their lesser, younger peers. When one can and does pay a dividend, it helps distinguish the two. When neither do, it can be that much harder. I leave it to the ever-so-honest brokers and investment bankers of Wall Street to determine whether too many companies without profits or the prospect of profits have made it to the public markets in recent years.

Finally, it is worth observing that nothing in the current arrangement is illegal in an SEC sense. And much of it has been blessed by the share-price-focused academy. It is certainly supported enthusiastically by the financial services industry.

But I continue to aver that a nearly dividend-free market is an anomalous situation and one that I expect to change significantly in the decade ahead. That need not happen as a result of legislation to tax or ban buybacks or other explicit government interventions. While buybacks were legalized by an SEC rule change in 1982, they skyrocketed for other reasons discussed here. Those same factors may reverse. Intel, for example, has properly concluded for its own business reasons that it is time to stop playing the casino with company money. That is a business decision that I expect to see more companies follow in the years ahead.