The magnitude of the financial collapse currently facing the airline industry is unprecedented. In 2020, the Big Four airlines that dominate the U.S. industry (American, Delta, United, and Southwest) reported GAAP net losses of $31.5 billion and operating losses of $33.1 billion.1 This was a $50 billion decline in operating income versus 2019. Between January and September, these carriers’ aggregate debt increased from $75 to $129 billion. Carrier press releases cite a $33 billion cash drain between March and December, although independent Wall Street estimates suggest much higher cash burns.2

The results for the three legacy carriers (American, Delta, United)3 are especially awful, and they face much greater liquidity and solvency challenges than Southwest. But the grimness of the overall picture was highlighted by Southwest CEO Gary Kelly who said that despite his airline’s stronger position, revenues would need to double just to reach cash breakeven.4

As the cash drains indicate, cuts to full-year operating expenses ($50 billion) have not come anywhere close to what is needed to offset total revenue losses ($100 billion). There is little airlines can do outside of bankruptcy to eliminate aircraft ownership costs, airport and facility rents, debts, IT, and other corporate infrastructure costs. The airlines have huge excess capacity as they were only able to shed 3 percent of their mainline aircraft by the end of September. Labor costs have only been reduced 19 percent because cuts outside of bankruptcy require either major incentives to get employees to voluntarily accept temporary furloughs or involuntary layoffs that must start with the least senior, lowest-paid staff.5 American CFO Derek Kerr has acknowledged that his airline has largely exhausted the potential for cost cuts; reversing cash drains will therefore depend on revenue recovery.6

While this paper will focus on U.S. airlines, similar economic damage has hit carriers worldwide. Outside the United States, airlines and governments have been more willing to openly acknowledge the severity of the crisis and many carriers have either filed for protection under bankruptcy laws or are undergoing major government-supervised restructuring.7 IATA, the industry trade group, estimates that industry losses worldwide in 2020 will exceed $118 billion.8 Air Canada CEO Calin Rovinescu said coronavirus impacts were “hundreds of times worse than 9/11, SARS, or the global financial crisis—quite frankly combined.”9

Coronavirus has crippled the trade and tourism activity that is the underlying source of airline demand. The legacy business model has been especially devastated; the higher-yielding corporate and international travel it depends on has fallen more than 90 percent. There is ongoing speculation about how much business demand will be lost indefinitely—some estimates suggest one-third—given the market’s ready adoption of substitutes such as teleconferencing and acclimation to much lower levels of business travel.10

Efficiency has also plummeted because the industry’s ability to tightly align costs and capacity with revenue and achieve extremely high asset utilization (for example, 2019 load factors of 85 percent) has collapsed. Nobody knows exactly where (lower) post-pandemic demand will stabilize, and reducing airlines’ permanent cost structure to that level will be a messy process—one which has barely begun. Transition costs and big pandemic losses must somehow be recovered. Reduced efficiency and scale will force bigger fare increases and service cuts, reducing demand further.

Two Possible Recovery Paths

Expectations that pre-pandemic conditions would magically return once vaccine production started were always a fantasy. A meaningful recovery process cannot begin until virus suppression rates around the world reach the point where widespread travel won’t create risks of new infection spikes and international border restrictions can be fully lifted. A best-case vaccine distribution and effectiveness scenario could allow a meaningful recovery to begin within the first half of 2021, but less-than-best-case scenarios could push the starting point into 2022. Until then, airlines’ ability to reduce their severe cash burn will be very limited, and any recovery will start from the most depressed demand and operational efficiency levels in industry history.

In addition to the question of how long it will take for a meaningful demand rebound to begin, it remains to be seen how much of the industry’s prior performance can eventually be restored. After the virus is suppressed, it is possible to imagine two industry recovery paths: Will the industry gradually return to its pre-pandemic efficiency, revenue, capacity, and growth path? Or will the damage to underlying structural economics produce a “new normal” well below previous performance?

The broader public interest lies in having as much future airline service as possible at the lowest prices that can be provided on a sustainably profitable basis. If shopping malls and cruise ships can only restore a portion of their pre-pandemic business, the economic losses would be limited to the directly affected workers and investors. But a wide range of trading and tourism industries depend on abundant, economical airline service (and those industries are also struggling to recover from major coronavirus damage), as do a large number of supporting industries (aircraft manufacturing, airports, internet travel services, etc.), so a less than maximally efficient airline recovery would cause broader economic damage.

The key to the recovery question is the industry’s ability, after virus suppression, to increase efficiency and to convert those efficiency gains into the lower prices that can accelerate the recovery of demand. As will be discussed below, the path to recovery—and even improved efficiency and growth—was established decades ago, during the long history of airline crises. Demand and profits collapsed after fuel prices suddenly tripled in 1973 and again in 1980. In 1990, a recession triggered by a smaller (40 percent) fuel price spike, combined with the effects of overexpansion, led to another industry crisis. Overexpansion prior to the end of the dot-com boom led to a larger crisis in 2000, as did the 2008 Great Recession.

Since the 70–80 percent coronavirus-driven revenue collapse is much larger than previous declines, however, the public interest in the strongest possible recovery demands an unusually aggressive response. The last two downturns (around 2000 and 2008) caused airline traffic to decline only 6 percent and 9 percent, but it took four years for industry revenue to fully recover in both cases. The post- dot‑com supply/demand imbalance forced all of the legacy carriers to undergo major bankruptcy restructuring (except Continental, which had already gone through two bankruptcies).

As with the post-dot-com crisis, very real threats of bankruptcy loom over the legacy carriers (though not Southwest). Indeed, even legacy bankruptcies might not be enough to escape the current crisis. Past industry-wide crises of this magnitude usually required proactive government interventions, such as those currently being pursued in other countries. These approaches included federal funding (in return for controls ensuring that taxpayers were rewarded for their investment), the establishment of a special federal agency (used in past cases where an entire industry needed major restructuring, e.g., freight railroads, steel, car manufacturers11), and temporary nationalization.

The Fundamental Conflict between

Airline Equity and Overall Economic Welfare

Unfortunately, the U.S. airlines seem to be deliberately ignoring both the magnitude of the current crisis and their ample historical experience in recovering from crises. The industry requires a much more ambitious restructuring effort than has ever been undertaken before, and it needed to start six months ago. This did not happen, however, because there is a fundamental, irreconcilable conflict between the interests of the airline owners in preserving the value of their equity and the public’s interest in taking the actions necessary to ensure the most efficient possible future service.

Instead of beginning a difficult recovery effort, U.S. airlines have spent months obscuring the depth of the crisis. First, the airlines insisted that the coronavirus problem was akin to a ship dealing with a major storm but that clear skies would quickly return. When it became obvious that this was not a passing storm, the industry behaved as if problems in the engine room were causing delays, but insisted repairs would restore full efficiency within six to twelve months. In reality, however, the industry had hit an iceberg. If dealt with immediately, there would be no risk of the ship sinking, but the damage would reduce the ship’s performance for an indefinite period and would take extensive work to fix. Yet the airlines’ refusal to urgently address their serious structural issues have only made these problems much worse.

Instead of beginning the necessary restructuring process, the executives of all four airlines have been single-mindedly focused on protecting current equity holders, because those owners would like to capture all the gains from any post-pandemic stock appreciation. Bankruptcy restructuring was critical to industry recovery in every previous post-deregulation crisis and would allow the airlines to rapidly stem their current cash drains and bring costs back into line with reduced revenues. But that is totally off the table because it would wipe out current equity holders and threaten bondholders and other major investor groups. Broader, industry-wide, government-supervised options are even further beyond the pale.

Doug Parker, CEO of American (the carrier seen as the most likely to file bankruptcy because it had the largest pre-pandemic debt load) emphatically ruled out any restructuring option. “Bankruptcy is failure. We’re not going to do that. I don’t think people should view bankruptcy as a financial tool; it’s failure.”12 Having been involved in multiple prior bankruptcy cases, Parker fully understands that bankruptcy would not mean the failure of American Airlines’ business. He is simply focused on protecting its current shareholders from failure.

In March, Congress provided $50 billion to the industry through the cares Act, half in grants conditioned on retaining staff through September, and half in loans at below market rates with very few conditions. That cash ($43 billion of which went to the Big Four) did nothing to improve efficiency or market demand, or address the massive gap between revenues and costs. The sole purpose of the bailout was to transfer wealth from taxpayers to the owners of these airlines by creating a “too big to fail” put. Congress signaled that it was committed to doing whatever it took to protect the industry’s ownership and control status quo. Even though the airlines did not have a plausible plan to close their massive cash drains, the subsidies prevented equity values from collapsing towards zero and allowed current owners and managers to raise an additional $40 billion from lenders who had been effectively told that they did not have to worry about bankruptcy risks. The combination of the subsidies and the loans they made possible account for essentially all of the Big Four’s current liquidity. Without this “too big to fail” put, it is possible that all of the legacy carriers would already be in bankruptcy.

Once taxpayers provided some limited access to capital markets, the legacies were desperate to raise whatever funds they could, and ended up pledging almost every unencumbered airplane, airport slot, trademark, and route authority as collateral and paying interest rates as high as 10 percent.13 This process of burning the furniture to keep the house heated even required surrendering control of the cash generated by the airlines’ frequent flyer programs—a maneuver which depended on the highly questionable claim that the spun-off programs would be worth substantially more than the programs combined with the rest of the airline.14

The efforts of current owners to capture all future equity appreciation are an attempt to subvert long-standing bankruptcy precedents. Under a conventional reorganization process, owners of companies whose business models collapse—which hemorrhage cash for extended periods and which cannot meet ongoing financial obligations—do not get to keep exclusive control of the company. In a bankruptcy, equity owners are assigned the lowest claim on the assets of the company and are often completely wiped out. On the other hand, parties that provide funding to prevent a financial collapse (taxpayers in this case) should receive one of the highest priority claims. But allowing courts or government agencies to have any say in the current airline recovery process would allow them to point out current ownership’s responsibility for multiple pre-pandemic problems that contributed to the present crisis.

One of the many preexisting problems was the $42.4 billion of cash these airlines have squandered on stock repurchases since 2014. Designed to inflate short-term equity values, stock buybacks exceeded the free cash flow these airlines were generating, increasing Big Four airline debt from $47 to $75 billion since 2015. These buybacks eliminated the reserves needed to cope with an inevitable downturn.15 All of this was done at the direction of the Big Four corporate boards, who had incentivized the four CEOs with $431 million in stock-based compensation.16

Today, the airlines’ complete refusal to pursue bankruptcy restructuring is a “bet the industry” proposition. These companies want outsiders to believe that they can achieve a full industry recovery under the current ownership and control status quo, without going through a restructuring in bankruptcy. But if they are wrong, and conditions do not rapidly improve, ongoing cash burns and asset erosion could make it impossible to salvage these businesses or achieve a strong recovery. Unfortunately, current owners have no incentive to reconsider their current course until the point at which solvency and survival are at risk. Immediately addressing the damage caused by the Covid-19 iceberg could have ensured the long-term integrity of the ship. But after months of insisting that they hadn’t hit an iceberg, and later that there was no structural damage to worry about, the risks of permanent damage to the ship are significantly increasing.

The Airlines’ Response:

Narrative Construction and Bailout Demands

Over the last year, the industry has engaged in a massive effort to deceive the public (and perhaps themselves) about the causes and severity of the collapse. At the same time, Washington has emphatically and consistently sided with the interests of airline shareholders against broader stakeholder interests in long-term industry efficiency and consumer welfare. The media has not only fully endorsed the industry’s view of the crisis, but has largely excluded any public discussion about alternate paths forward or the distinct interests of consumers and taxpayers.

From the beginning of the crisis, the industry developed a political narrative designed to obscure the central conflict between the desire to protect the current ownership and control status quo and the more aggressive restructuring required to quickly recover and maximize future industry growth. This was designed to prevent any suggestion that there was an alternative to preserving existing equity control, such as bankruptcy restructuring or government intervention. As with other industries in which coronavirus impacts exacerbated serious preexisting problems (retail, commercial real estate, etc.) this narrative also served to protect current owners and managers from blame for any failures. The objective was to lock in all prior gains, while socializing all of the losses since March.

The original narrative justifying the first $50 billion in taxpayer subsidies emphasized that Covid-19 losses were a temporary problem and had not damaged industry fundamentals. The absurdity of these claims was clear by April—a rapid “V-shaped” recovery of corporate and international traffic wasn’t going to start that summer, and the “one-time” subsidies obviously did nothing to close the enormous gap between costs and revenues. But the media continued to repeat the narrative because, even into the late fall, every forecast prepared by industry insiders reinforced the rapid “V-shaped” storyline that the dominant carriers were pushing.17

These narratives insisted that even though the 2020 revenue collapse was an order of magnitude greater than the largest previous crisis, revenue would recover faster than ever before. Yet virtually no one questioned the plausibility of these forecasts. The original March cares Act funding was also deliberately misrepresented as being primarily for the benefit of beleaguered airline workers. But since the airlines were adamantly opposed to bankruptcy restructuring, no employee contractual rights were at risk. The industry’s claims obscured the huge value that Congress created for existing stockholders, and blocked discussion of why taxpayers should replenish all the cash that equity holders had distributed to themselves through extractive stock buybacks. Also ignored was the question of why taxpayers—after providing almost all the liquidity needed for the airlines to continue operation—should let the current owners, who provided no new funding, capture 100 percent of all future equity appreciation.

Society would obviously be harmed if the assets (aircraft, hubs) and management skills (ability to maintain aircraft and manage complex networks) of the major airlines collapsed into a pile of rubble and had to be rebuilt from scratch. But even in the nastiest scenario imaginable, preserving industry capacity is separate from maintaining the ownership status quo. A major objective of the industry’s PR narrative has been to falsely conflate the preservation of industry capabilities with the preservation of the current ownership structure and executive compensation programs.18 Mainstream media coverage, however, has explicitly endorsed the industry’s preferred framing—“saving the industry requires saving equity”—which has distracted attention from other restructuring options that could more successfully support critical industry capabilities.

Since the initial $50 billion in taxpayer subsidies did not come anywhere close to stemming the industry’s terrible cash drain, the Big Four U.S. carriers spent the summer and fall lobbying for a second tranche of subsidies from Congress. The industry hoped that no one would notice that the request for onetime temporary assistance had been quietly transformed into a demand for ongoing, open-ended subsidies. While they originally sought $25 billion, six months of lobbying finally produced another $15 billion transfer from taxpayers to the airlines in late December.

The revised industry narrative claimed that the new bailout funds would save thirty-eight thousand jobs, which the industry eliminated once the original subsidies expired in September. Luckily for the industry, the media uncritically repeated this “saving jobs” narrative and never bothered to explain that the funds wouldn’t increase airline service anywhere, or that there was no useful work for these thirty-eight thousand people to do, or the implication that taxpayers were paying $400,000 to protect each job for just three months.

The direct link between taxpayer bailout funds and the preservation and enrichment of the ownership and control status quo was further highlighted when Southwest turned down its final set of cares loans. Southwest insisted that the loan terms designed to ensure taxpayer funds were not used on executive bonuses and stock buybacks were too “onerous.” Immediately after turning down nearly $3 billion in low-cost loans in order to protect potential insider gains, it demanded that all employees agree to 10 percent pay cuts.19

After an ugly third quarter, the industry began rolling out a new narrative: claiming that the crisis is already over. This narrative absurdly assumes that “capital markets” are not only fully capable of solving a crisis of this magnitude, but that they already have. In other words, the claim is that airlines have raised more than enough liquidity to sustain operations until coronavirus has been beaten. United CEO Scott Kirby said cash burn had seemed like an important metric at the start of the pandemic, “But that’s not at issue anymore. We have enough liquidity to get through the crisis,” and we are now refocused on “winning the recovery.” Delta CEO Ed Bastian said the money it had raised gave it a “good line of sight to positive cashflow by the spring.”20

Needless to say, the reporters following the story happily publicized the new “crisis is over because we have all the cash we’ll ever need” narrative without noting that the industry’s desperate cash raises could not have happened without the congressional “too big to fail” put. They also ignored the new narrative’s contradiction with the industry’s desperate lobbying for tens of billions in new subsidies.

A History of Airline Industry Crises

How far will the industry’s actual recovery from the coronavirus crisis fall short of the ideal-case recovery—the recovery that would maximize overall economic welfare? And is there anything that can be done at this point to reduce that shortfall? A brief detour through airline history can help answer these questions, which hinge on the industry’s ability, after the virus is suppressed, to maximize efficiency and stimulate growth through lower prices.

The recent history of the airline industry can be divided into two distinct periods: the two decades after the implementation of the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 and the first two decades of the twenty-first century. Critical economic indicators steadily improved in the first period but stagnated or declined in the second. I will use the terms “liberal competition” and “radical consolidation” as shorthand labels for these two periods.

In the liberal competition period, the airline industry learned what was required to increase both industry efficiency and consumer welfare, and thus how both airline owners and the overall economy could prosper. The factors that drove productivity gains and industry growth in this first period were also critical to full and rapid recoveries from a previous industry crisis.

The changes in the radical consolidation period reduced efficiency and growth, while also creating the major obstacles that will limit the industry’s recovery from the coronavirus catastrophe. These changes were triggered when much of the industry collapsed into bankruptcy after the end of the dot-com economic boom and began (with Washington’s active support) a counterrevolution against the liberal competition of the late twentieth century. This produced today’s conflict between airline owners and broader economic welfare.

Figures 1–321 document these major changes in industry economic performance and show that there has always been a powerful relationship between efficiency (illustrated here by changes in real unit costs), consumer welfare (changes in real prices), and overall industry growth (available seat-mile capacity). Figure 3 shows the breakdown between major industry sectors, including the domestic and international operations of the legacy carriers, the regional carriers that use smaller aircraft to feed legacy mainline hubs,22 and the “low-cost carriers” (LCCs) that had been restricted to intrastate operations before deregulation, but subsequently became a major provider of interstate domestic service.23

The strongest cost efficiency improvements (5 percent average per year, from figure 1), the fastest price reductions (4.5 percent average per year, from figure 2), and the strongest growth (14 percent average per year, from figure 3) occurred in the 1960s. The problem was that, under Civil Aeronautics Board regulation, industry gains were dependent on exogenous GDP growth and external technological innovations, principally the conversion from propeller aircraft to jets. If a recession occurred, or breakthroughs in engine and aircraft technology weren’t occurring, industry productivity gains slowed to a trickle, as seen in the 1970s after the conversion to jets was complete.

The industry’s first major crisis was the 1973 oil shock, when fuel costs increased from 10 to 30 cents per gallon. The regulated industry could not suddenly restructure assets or generate the new efficiency improvements needed to quickly stem losses and restore growth. This lack of flexibility and dynamism helped convince the industry and Congress that the regulatory status quo was not sustainable.

Despite increasing headwinds (the 1980 and 1990 fuel spikes, along with inflation), real cost efficiency improvements (averaging 2 percent per year), real price declines (3 percent per year), and faster growth (averaging 5 percent per year) returned in the two decades after deregulation. Since the gains from major external technological innovations had been largely exhausted, airlines had to develop their own sources of growth, and the competition unleashed by deregulation spurred a wide range of improvements. Unlike in 1973, the deregulated industry was able to quickly recover from the equally large 1980 fuel spike and the 1990 overcapacity and fuel-price-driven crisis.

Since 2000, however, there have been no overall industry efficiency or consumer welfare improvements. In fact, the performance of the legacy sector began to seriously deteriorate, especially in domestic markets. Recoveries from the 2000 dot-com crisis and 2008 financial crisis were slow and difficult.

Legacy domestic costs have increased about 1 percent per year and are now $10–15 billion higher per year than they would be if the legacy carriers had maintained their 2000 real unit cost levels. At the same time, LCCs began operating an increasing share of both domestic and international flights, exploiting a sudden jump in long haul aircraft technology. The net result is stagnant overall industry performance. The one apparent bright spot—the unit cost drop after 2015—is entirely due to the collapse in fuel prices, which also explains most of the recent (pre-pandemic) increases in airline stock prices.

Instead of raising base domestic fares when the dot-com recession ended to offset rising costs, the legacy carriers began imposing stiff fees for services (baggage, snacks, ticketing changes) previously included in ticket prices.24 This increased unit (total) revenue 2.6 percent per year in new fees, resulting in $25 billion of higher passenger payments by 2019. Meanwhile, despite small unit cost improvements, the LCCs also stopped reducing real fares since they could steadily raise fares (2.1 percent per year) while remaining under the increasingly higher legacy pricing umbrella.

As the capacity chart illustrates, legacy domestic operations declined by around 2.5 percent per year between 2000 and 2015, before a brief growth spurt after fuel prices collapsed. Legacy domestic operations, which accounted for 80 percent of total industry capacity prior to deregulation, declined to 60 percent by 2000 and to 36 percent in 2019. Thus the media narratives that conflate the problems facing the three large legacy airlines with “the industry crisis” badly misrepresent reality. Recent overall industry growth has been almost entirely driven by the LCCs, which were growing nearly 7 percent per year.

Liberal Competition Drives Innovation and Growth

The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) limited competition in order to nurture industry growth in its early years but had no ability to adapt to major market and technological changes. For forty years, this sclerosis locked the incumbent legacy airlines into a single business model with increasingly inefficient route networks and a rigid segregation of trunk, local service, and international operations. The CAB’s static industry structure was roughly workable in the DC-3/ Stratocruiser era but was clearly obsolete in the 747/737 era.

Reforming an industry structure inevitably creates winners and losers. The largest incumbents (such as United, Pan Am, and American) recognized that attempts to reform the regulatory system would threaten the lucrative routes and unassailable dominance they enjoyed. Instead of focusing on ways to improve efficiency and service, they focused on lobbying efforts to block serious change. Their effective veto created a sclerotic situation that represented a paradigmatic case of “regulatory capture.”

The ability of the major carriers to protect their short-term interests turned the CAB into the enforcer for a loose but effective cartel of industry incumbents.25 Life for airline managers was easier under CAB regulations, but results in good years were mediocre, and dismal in bad years. Eliminating “regulatory capture” was one of the major justifications for deregulation since giving the largest incumbents the artificial power to produce more favorable results than they could achieve in a competitive market was obviously reducing industry efficiency.

Deregulation did not liberate the industry from government oversight, but the central objective of that oversight changed. The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 explicitly rejected the incumbent protections of the CAB era. The new primary focus would be on protecting the robust competition needed to maximize overall industry efficiency and consumer welfare. Deregulation was never designed to affect other critical oversight functions that helped protect robust, level-playing-field competition (e.g. antitrust, labor and consumer protections, financial reporting, bankruptcy) because no one thought that eliminating those protections would increase efficiency or consumer welfare.

There are numerous examples of post-deregulation innovations that led to major, tangible productivity and service improvements. Eliminating the CAB’s business model straitjacket led to the development of the LCC sector, which achieved much lower unit costs in high-demand markets and aggressively used that efficiency advantage to stimulate market growth via lower fares. LCCs eventually captured 45 percent of the domestic market. In addition, rapid hub expansion increased legacy operational efficiency and allowed for full integration of international and regional routes into domestic hub networks.

Other major innovations that resulted from greater competitive pressures include the development of sophisticated pricing systems that drove big increases in revenue productivity, computerized reservation systems (CRSs) that massively reduced distribution costs, and airlines recapturing control of the point of sale. This period also saw the introduction of frequent flyer loyalty programs, one of the most powerful marketing innovations of the twentieth century.

“Reduced barriers to exit” does not get mentioned as much as deregulation’s “reduced barriers to entry,” but it was even more important to increasing efficiency, welfare, and industry growth in the 1980s and ’90s. As the critics of regulatory capture had observed, Schumpeterian “creative destruction” is a dynamic process and cannot work if powerful incumbents can rig results in order to protect the static status quo and block the shift of industry resources to more productive uses. “Creative destruction” also requires a resilient industry structure, with a reasonably large number of competitors, so that the mergers and liquidations needed to recover from a crisis do not threaten future industry competitiveness.

Reduced barriers to exit were critical to accelerating the recovery from multiple industry crises, including the 1980 and 1990 fuel-price-driven recessions. For the first time, airlines with long histories—such as Braniff, Eastern, Pan Am, and (a few years later) TWA, and dozens of recent start-up carriers—were allowed to die.

Figure 4 documents the huge role of major restructurings in this era, which could not have occurred under the CAB. The list includes cases where a failing carrier transferred viable assets (e.g., the Newark hub, international routes) to a stronger carrier, cases that liquidated the weakest industry capacity (the domestic operations of Pan Am, Braniff, and Eastern, failed start-ups like Air Florida), and four major cases (Northwest, the two later Continental filings, America West) where a viable but temporarily illiquid carrier moved quickly to file for bankruptcy protection and emerged as a much stronger competitor.

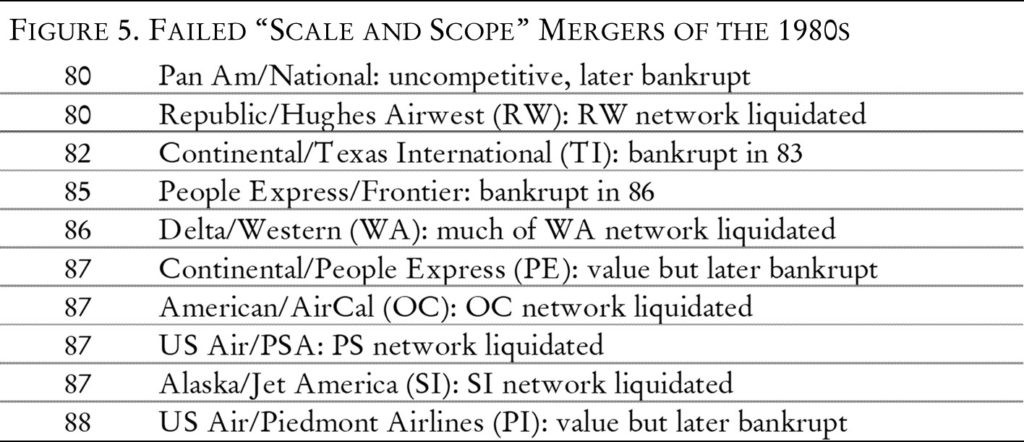

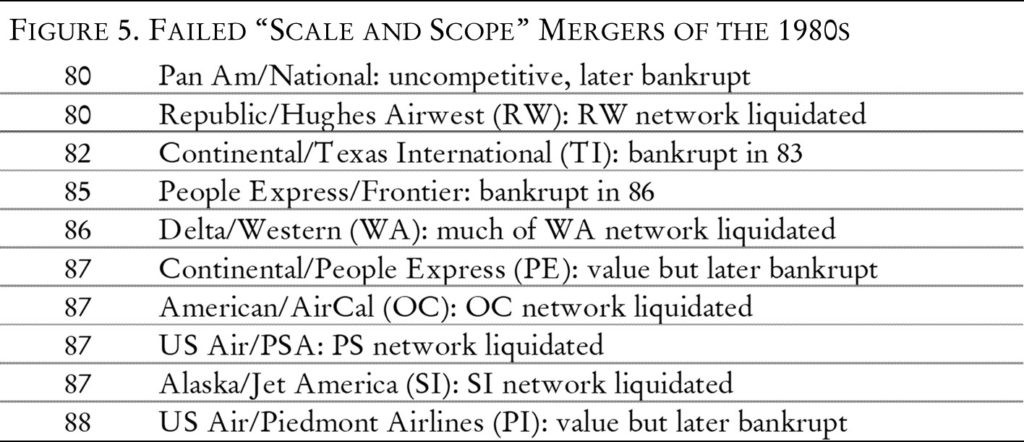

While bankruptcy-type restructuring usually led to big improvements in productivity, another lesson from this era is that mergers almost never did. Four of the cases listed in figure 4 were mergers that integrated previously uncompetitive hubs (Detroit, St. Louis, Houston, Minneapolis), but these problems (originally created by the CAB) had all been fixed by 1987. A couple of bankruptcy restructurings were nominally structured as mergers (ValuJet-AirTran) and only worked because assets were transferred at fire sale prices.

Aside from those special cases, all of the ten mergers shown in figure 5, where the primary objective was to expand the operating scale and network scope of the acquiring carrier, were major failures. Not only did merger synergies fail to cover merger costs, but in each case the merged carrier either quickly went bankrupt or liquidated the route network it had just acquired.27 Consolidation for consolidation’s sake reduced industry efficiency. Economies of scale can be powerful at a specific hub but are limited elsewhere. Network scope has some value, but not enough to justify merger acquisition premiums and integration costs. Indeed, the uncompetitive capacity arising from these mergers and other hub expansions made the industry downturn after the 1990 recession worse, leading to the bankruptcies of the early ’90s.

By contrast, the major asset reallocations that resulted from the restructurings of the 1990s (and various strategic and network changes that immediately followed) not only helped the industry recover from the 1990 collapse, but by 1995 had led to the strongest post-deregulation profitability ever achieved prior to the 2015 fuel price collapse.

Northwest closed four uncompetitive hubs, developed an innovative new alliance with KLM, and concentrated almost all service on its four strongest hubs. This strategy of reallocating resources to very strong hubs led to major profit improvements and was quickly copied by Continental (which closed weak hubs in Denver, Cleveland, and Greensboro) and American (which closed San Jose, Nashville, Raleigh‑Durham, and San Juan). Five of the seven large legacy operations on the West Coast and five of the eight large operations in the Northeast were drastically downsized.28

Another breakthrough occurred in intercontinental markets, which had been totally ignored in the 1970s deregulation debates. These markets remained extremely inefficient until the early ’90s because they were governed by bilateral treaties that (like the CAB’s regulation of U.S. domestic competition) were primarily focused on protecting the large incumbent carriers, which most governments saw as instruments of national prestige and trade policy. The problem was that almost half the traffic on the North Atlantic was in smaller markets (such as Houston-Munich or Denver-Zurich), but neither U.S. nor European carriers could profitably serve these areas with their own aircraft. All of these passengers were therefore limited to high-price and low-quality interline connections. The innovative breakthrough here was the North Atlantic collusive alliances of the mid-’90s.

With antitrust immunity to collude on scheduling and pricing (facilitated by the 1993 U.S.-Netherlands “Open Skies” treaty), Northwest and KLM offered a fully integrated service to the entire North Atlantic market. This collusive alliance model was soon copied by Delta/Swissair/Sabena (1995) and by United/Lufthansa/SAS (1997), rendering interline connections extinct. These alliances created huge consumer welfare benefits (average North Atlantic fares fell by 8 percent while capacity increased by 54 percent) because they overcame a major network efficiency barrier. These gains came without significantly increasing market concentration, as the three collusive alliances still only served 42 percent of the North Atlantic market in the late ’90s. But the ability to improve international market efficiency through increased competition never went beyond these mid-’90s innovations and was soon reversed.

The Counterrevolution against Liberal Competition

By the end of the twentieth century, following a messy and painful learning process, it was clear that robust competition, supported by government oversight to ensure a level playing field, was necessary to drive ongoing improvements in overall industry efficiency and consumer welfare. Increased competition made management’s job much harder, but carriers that did a better job dealing with industry economics and marketplace dynamics than their competitors would receive greater rewards.

Deregulation did not eliminate economic cycles or the laws of supply and demand, however. Managers still needed to ensure that overall industry capacity remained aligned with revenue potential, focus network assets on markets where they had sustainable competitive advantage, and avoid fleet investments that could not earn returns over a full business cycle. The superior financial performance of Southwest Airlines in recent decades is best explained by its strong focus on competitive advantage and full-cycle finances. On the other hand, most of the industry crises were due to the failure of many legacy carriers to respect those basic economic principles.

United, Delta, and Continental (and to a lesser extent USAirways) saw the big improvements in mid-’90s industry profitability as a signal to engage in foolish overexpansion,29 and an overcapacity-driven industry crisis hit in 2000. These carriers tried to compete for every possible passenger regardless of the overcapacity risks or their significant competitive disadvantage outside their largest hubs. They were anxious to capture all of the traffic growth available at the peak of the dot-com boom, ignoring the fact that the inevitable cyclical downturn would make their new aircraft purchases horribly unprofitable. This led to the biggest industry collapse up to that date, which forced almost all legacy capacity into bankruptcy protection. USAirways was under chapter 11 protection from 2002 to 2005, United 2002–6, Hawaiian 2003–5, Aloha 2004–6 (plus chapter 7 in 2008), Delta 2005–7, Northwest 2005–7, and American 2011–13.

The counterrevolution against liberal airline competition began during these legacy bankruptcies. The managers of these airlines rejected marketplace discipline for failed strategies. They refused to accept any accountability for their bankruptcies, instead blaming the crisis entirely on Osama bin Laden, even though the economic recession began in 2000, and capacity increases had begun reducing industry yields in early 1999, two and a half years prior to 9/11.

Deregulation had produced two decades of consumer benefits and overall industry growth, but continually developing innovations that improve service and productivity is very difficult work. Legacy managers wanted a simpler and easier path to steady profitability and industry dominance. The counterrevolution sought to replace liberal competition with results rigged to favor the owners and managers of the largest incumbents.

This counterrevolution required four major changes: (1) The subversion of the bankruptcy restructuring process such that, instead of disciplining bad decisions and fixing industry problems, it became a means of entrenching the management and strategic status quo, as well as a tool for personally enriching senior executives. (2) Replacing a variety of short- and long-term business metrics with a single-minded focus on near-term stock price appreciation. (3) Achieving a much greater level of regulatory capture than had ever existed in the CAB era, with officials abandoning long-standing policies designed to protect competition and consumers in order to focus exclusively on what the owners of the largest incumbent airlines wanted. And (4) a carefully orchestrated, multiyear effort that shrank the robustly competitive North Atlantic market (the largest airline market in the world) to a permanent three-player cartel and converted the strongly competitive U.S. domestic market (the second-largest market) into an oligopoly dominated by four companies.

Bankruptcy as a Sword, Not a Shield

Firms enter bankruptcy when a business failure is so large that contractual obligations cannot be met. The bankruptcy laws were designed to maximize the post-reorganization value of the company in order to maximize the recoveries to creditors whose contracts had been violated. Transparent bankruptcy rules ensure creditor repayments follow priorities established by law, including the preferences given to those providing fresh at-risk capital.

In the post-2002 cases, these rules were subverted by an alliance between airline executives and the banks that issued their frequent flyer affinity credit cards. The banks were anxious to protect sweetheart contracts for these staggeringly profitable cards, which, if renegotiated, would provide more cash for other creditors and the corporate recovery. The banks therefore provided debtor-in-possession financing on the condition that the managers who had signed the agreements favorable to the banks—and had led the airlines into bankruptcy—retained exclusive control of the reorganization process. Creditors were thus blocked from presenting competing plans that could have replaced management or forced the banks to accept less advantageous terms.

In addition, bankruptcy courts began to automatically grant draconian cuts to existing labor contracts. These cuts were allowed under law only if the company produced objective evidence that it would not be able to avoid liquidation without such measures, and that all comparable creditors were similarly impaired. None of the laws had changed, but courts began accepting unsubstantiated management assertions as sufficient evidence and never imposed similar reductions on contracts with lessors, airports, banks, or anyone else.30 The essentially automatic acceptance of the airlines’ assertions that they could not reorganize without massive labor cuts even held in the 2011 American bankruptcy. When American filed in 2011, its finances were much stronger than they are today. It was cash flow positive, had over $4 billion in unencumbered cash reserves (more than it had at the end of 2019), did not require debtor-in-possession financing, and the post-2008 demand recovery was well underway.31 This departure from prior bankruptcy procedure transferred significant wealth from labor to capital.

In the twentieth-century bankruptcies, the airlines all emerged within eighteen months and were more efficient and more competitive when they emerged. The post-2000 bankruptcies were much different. United, for example, remained in bankruptcy protection under CEO Glen Tilton for four years, because his plan to protect the ownership and control status quo couldn’t produce any meaningful financial improvements until general economic conditions had fully recovered. Tilton personally pocketed $30 million, and United remained weak for another decade.

To take another example, American agreed to include massive new fleet purchases in its reorganization plan in exchange for agreements from Airbus and Boeing to support CEO Tom Horton’s fight against USAirways’s superior reorganization proposal. American’s final emergence was delayed for eighteen months until creditors agreed to pay Horton $10 million (even though his plan was totally rejected) and accept the extravagant aircraft purchases. These fights caused lasting damage, giving Delta and United a significant marketplace advantage for eighteen months, and the substantially higher debt load left American in an extremely precarious situation when coronavirus hit.32 In addition to protecting equity holders, American’s current refusal to consider bankruptcy keeps these fleet obligations in place.

The counterrevolution also changed the fundamental corporate objectives of these airlines. The hedge funds willing to invest in the reorganized airlines demanded a single-minded focus on stock price appreciation and substantially strengthened links between executive compensation and equity appreciation. This killed the idea that by using resources efficiently, and by increasing employment and service through profitable growth, airlines could benefit both their investors and improve overall economic welfare. Airlines now only existed to serve the interests of capital accumulators. As long as stock prices increased, it did not matter if efficiency and growth declined, or that gains to capital had been extracted from employees, suppliers, or customers.

Reducing Competition

Radical industry consolidation was driven by the concerted efforts of the largest U.S. and EU intercontinental carriers. Lufthansa, Air France, United, and Delta were all struggling after losing share to more efficient carriers33 and rebelled against the competitive market forces that had undermined the dominance and profit margins to which they felt entitled. Only a brief summary of this history can be provided here, but much more extensive versions have been published.34

The first phase of consolidation involved mergers that would absorb the entire North Atlantic market into the three collusive alliances that had been established in the mid-’90s. The alliances that had successfully increased competition and consumer welfare would now be used to accomplish the opposite. Although the original ’90s alliances eliminated major network inefficiencies, the post-2004 alliance combinations did nothing to improve efficiency. The carriers knew that the North Atlantic was highly profitable under competitive conditions and would be far more profitable under cartel conditions.

To support this process, the intercontinental airlines launched a massive “consolidation is inevitable” PR campaign (led by Glen Tilton in the United States) that totally dominated airline coverage in the industry and business press. A totally one-sided public debate ensured that the media never had to evaluate competing claims and that government officials who went along with the industry would face little scrutiny. These arguments included, for example, that consolidation would not harm consumers because recent new entrants ensured ample competition and that consolidation was necessary because there were actually too many airlines.

This narrative, however, was completely false. All of the new market entry was limited to short haul (domestic and regional) markets, mostly in rapidly growing economies far from the North Atlantic. The mergers being advocated were designed to consolidate intercontinental markets that had always been competitively stagnant.35 But the press continued to repeat the industry’s “consolidation is inevitable” narrative and never mentioned that the changes being pursued were designed to reduce the number of meaningful competitors from eight to just three and increase the North Atlantic market share of the collusive alliances (Lufthansa-United, Air France–Delta, and British Airways–American) from 48 percent to 96 percent.

The triggering event for radical industry consolidation was the 2004 merger of Air France and KLM, which eliminated the main source of price competition in European long haul markets. Air France paid a 40 percent premium over KLM’s public market trading price, indicating how highly valued these reductions in competition were. Further, this merger essentially reduced the value of Northwest to zero, since it could not survive without a large North Atlantic network and alliance partner. Delta was able to acquire it for next to nothing. It also meant that Continental and USAirways could not survive independently. In short, once the three 1990s collusive alliances took over all of their previously independent intercontinental competitors, the mergers that reduced the U.S. domestic legacy sector to just three competitors were a fait accompli.

At the behest of the large incumbents, U.S. and EU government officials agreed to totally abandon the oversight based on level-playing-field competition that had produced thirty years of consumer welfare and industry efficiency benefits. Rubber-stamping every industry consolidation request effectively established a full laissez-faire regime where the most powerful companies could pursue their self-interest regardless of the impact on the rest of the economy. The industry thus achieved a level of regulatory capture far greater than anything seen in the CAB era. The extent of this government capture is illustrated by the DOT’s willingness to disobey long-standing legal requirements designed to protect consumers and competition. The agency failed to conduct required Clayton Act market power and market contestability analysis, failed to produce any verifiable, case-specific evidence showing that the reduction in competition was “required by the public interest,” and used the blatantly fraudulent claim that reduced competition always produces huge price cuts to meet the “necessary to achieve important public benefits” requirement.36

Industry PR falsely claimed that, despite substantially higher integration costs, the merged airlines would produce huge operating synergies. This claim ignored the fact that all of the similar “scale and scope” 1980s mergers failed because the synergies they produced were actually negative. The false claims about operating synergies masked the real objectives—reaching a level of concentration high enough to lock in government capture, to create anticompetitive market power, and ultimately to create a “too big to fail” put.

Carriers quickly realized the benefits of that artificial market power. North Atlantic price trends had closely tracked domestic price trends since deregulation, but (as shown in figure 6) after radical consolidation began in 2004, North Atlantic fares rose three times faster than domestic fares. As early as 2008, this meant the U.S. and EU North Atlantic carriers each earned $3 billion more than prior to the KLM–Air France merger.37

Consumer welfare losses continued to worsen as the remaining pockets of market competition quickly collapsed. Following classic cartel behavior, the three collusive alliances forced smaller European competitors to become junior alliance members on highly unfavorable terms and moved aggressively to lock long haul carriers from Japan, Korea, Australia, and other major Pacific markets into the three-player intercontinental cartel structure. The alliances also mounted a massive political attack on the three large independent Middle Eastern hub carriers (Emirates, Etihad, Qatar), even though their network overlap was extremely small.

Blatantly anticompetitive LCC mergers (Southwest-AirTran and Alaska-Virgin) were quickly introduced since it was clear that Washington could not object after having just waived through the previous, larger rounds of consolidation. This allowed the LCC sector to abandon its decades-long practice of steadily reducing real prices. Along with the artificial Atlantic pricing power and the ability of the consolidated domestic industry to impose stiff fees, this explains the twenty-first-century industry price increases shown in figure 2. While industry supporters insist that the nominal absence of entry barriers means the industry is fully competitive, the subversion of the bankruptcy process and captured government support for the largest incumbents not only rebuilt the barriers to exit that deregulation had dismantled but made them far stronger than they had ever been under the CAB. These barriers to exit were strengthened when the number of competitors was reduced, by design, to a point where the industry no longer had the resiliency to quickly restabilize after a crisis.

Claims that the shrinking of most airline markets to just three competitors posed no threat to consumers were obvious nonsense. It is only possible to discipline carriers that mismanage capacity and finances if there are enough competitors to pick up the slack. As even this very cursory review of airline history documents, competitive situations never remain stable for very long, and it was absurd to believe that the rough 2010 balance between the three international collusive alliances and the three U.S. domestic legacy carriers would last forever.

If any one of the three airline groups (or three U.S. legacies) began to lose significant share, the two stronger ones would immediately realize much greater artificial market power, the industry’s competitive balance would quickly collapse, and both consumer welfare and industry efficiency would suffer. This unsustainable three-player structure helped create the “too big to fail” put, since all of the three players knew that government would have to immediately intervene if any one of them faced serious difficulties. While no one foresaw the magnitude of the coronavirus collapse, some type of industry crisis was inevitable, and it was entirely predictable that the consolidated industry would not be able to deal with it.

Turbulence Ahead

Going forward, the public’s interest is in a rapid postvaccination recovery that restores as much airline service as possible at the lowest sustainable prices. Since demand and efficiency will be at uniquely depressed levels when virus suppression is finally achieved, the public interest requires a far more aggressive recovery program than the industry has ever seen before.

The obstacles to achieving this sort of recovery appear insurmountable, but they have little to do with the size of the coronavirus collapse, as massive as it was. They were created when the largest legacy carriers mounted a massive, well-organized counterrevolution against the liberal competitive regime of the late twentieth century. This was a political battle between airline owners’ financial interests and the public’s interest in maximizing overall economic welfare.

Today’s political battle as to whether any coronavirus recovery will favor airline equity holders or the public’s interest in the strongest possible industry restructuring is just a reflection of this previous battle, and the outcome was decided years ago. The public decisively lost, and all of the groups that had helped protect the public’s interest in the twentieth century (Congress, executive agencies, courts, mainstream media) have totally sided with airline owners and against competition and consumer welfare.

All of the industry’s behavior in the last nine months follows the same pattern as its response to the post-2002 bankruptcies, when the shift to consolidation and extraction began. Instead of developing innovations, the industry focused on developing PR narratives. Instead of ensuring that competitive forces reward the most efficient, the wagons were circled around the ownership and control status quo. In 2002, legacy carriers fought to avoid accountability for overexpanding before an inevitable downturn. In 2020, they fought to avoid accountability for extracting tens of billions in stock buybacks before an inevitable downturn.

The political power of airline owners has increased. In the 2002–7 bankruptcies, management’s position was totally protected and they reaped huge rewards despite causing massive competitive and financial damage. Despite the much larger coronavirus impacts, protections have now been extended to equity holders so they can get the exclusive benefits from any future equity appreciation. In 2002–7, creditor rights under bankruptcy law were distorted; in 2020, they were completely evaded. Airline owners have no intention of sharing future upside with the taxpayers whose $65 billion bailout prevented a complete collapse.

Maximizing the future efficiency and competitiveness of the industry is a lost cause. All evidence suggests the industry is on a path that fails to restore pre-pandemic revenue and efficiency levels. The remaining questions are how much damage will be caused by industry inaction while waiting for a meaningful revenue recovery to begin, and how much worse the eventual “new normal” will turn out to be. Burdening the public with a smaller, less efficient, and higher-priced industry in order to protect the ownership and control status quo is a form of value extraction, just like the exercise of artificial pricing power, or getting $65 billion in taxpayer subsidies.

One scenario is that virus suppression occurs rapidly, and airlines can muddle through the next few years of depressed demand without any major collapse. This requires meeting Delta CEO Ed Bastian’s current prediction that infections steadily decline from their January peak and a robust business demand recovery will be underway this spring.38 But in any “muddle through” case, the investments needed to strengthen operations will not happen, given extremely tight liquidity and heavy debt loads. Even under the most optimistic “muddle through” scenarios, legacy carrier market share losses will continue to increase beyond the ongoing pre-pandemic declines shown in figure 3. International traffic will recover slowly, and Southwest and other LCCs will be well positioned to capture a much larger share of domestic traffic. All of the historical evidence suggests that the legacy carriers will refuse to gracefully accept their diminishing competitiveness, and that attempts to retain market share will make their financial situation even more challenging.

Since these airlines have focused so heavily on value extraction in recent years, it would not be surprising if they double down on that strategy. Since growth in recent decades has come mainly from eliminating competition and exploiting market power, financial markets are likely to applaud any further efforts to tighten the screws on consumers and suppliers. The industry could decide to pursue more anticompetitive mergers, expand the scope of collusive alliances,39 and demand that governments accept whatever market rigging investors might require to lock in returns.

Unequal balance sheets and potentially uneven demand losses create the additional risk that market share battles between the three legacy carriers (on top of market share losses to LCCs) could destroy the industry’s fragile competitive balance. The airlines could somehow convince Congress to supply however many billions the industry says it needs until sustainable profits return. This would minimize the risk of disruption, but would likely produce no meaningful efficiency improvements or other external economic benefits.

Of course, various downside scenarios could provoke much deeper crises. It is doubtful that all three legacies can remain solvent if progress towards virus suppression and border reopening takes significantly longer than expected. If it becomes apparent that huge cash burns could continue throughout 2021, industry finances may erode to the point where it would probably be too late for any type of bankruptcy restructuring or government intervention to work.

All the tools that enabled the industry to quickly recover from the twentieth-century crises have since been destroyed. A true industry productivity renaissance would require a “counter-counterrevolution” to end reliance on value extraction, restore robust competition, and ensure the creation of overall economic benefits. At present, however, every force that could shape the airlines’ future—industry, government, finance, and the media—appears eager to thwart any movement in that direction.

This article originally appeared in American Affairs Volume V, Number 1 (Spring 2021): 37–68.

Notes

The author has no current financial relationship with the airlines discussed here.

1 Financial data are from the airlines’ published quarterly results. In 2019, the Big Four carriers and their regional partners accounted for 86 percent of the total U.S. airline industry. At the beginning of 2020 they had over 342,000 employees and operated 4,992 aircraft with another 1,185 aircraft on firm order.

2 Analysis by Hunter Keay of Wolfe Research puts airline cash drain estimates on an “apples to apples” basis, cited in Holly Hegeman, Plane Business Banter, October 23; and November 10, 2020. This analysis showed that negative cash flows were 54–144 percent higher than carrier-published cash burn numbers, which are not calculated on a consistent basis.

3 The legacy carriers were originally founded in the 1930s or earlier, and were the only airlines allowed to offer scheduled interstate service prior to deregulation in 1978.

4 Kyle Arnold, “Southwest Airlines Needs ‘Business to Double in Order to Break Even,’ CEO Says,” Dallas Morning News, August 28, 2020; Southwest’s advantage also applies to low-cost carriers in Europe such as Ryanair and EasyJet. Ben Goldstein, “S&P Global Sees Just Three Investment-Grade Airlines Left,” Aviation Week, August 12, 2020.

5 Delta took a $5 billion third quarter write-off for its program, illustrating that near-term labor savings are extremely limited.

6 Ted Reed, “When Will American Airlines Get to Breakeven Cash Flow?,” Forbes, November 12, 2020.

7 Bankruptcies to date include latam, Avianca, South African, Kenya, Norwegian, Virgin Australia, Virgin Atlantic, Interjet, Aeromexico, Thai, and numerous smaller carriers. Other government-supervised restructurings include forced mergers (e.g. Asiana into Korean, the proposed Japan Airlines-ANA merger) government capital infusions provided in exchange for major shareholdings and strategic control (Lufthansa, Air France), and formal re-nationalization (Air New Zealand, Alitalia).

8 Jens Flottau, “Airlines Bet on Traffic Comeback in Second Half of 2021,” Aviation Week, December 7, 2020.

9 CAPA Center for Aviation, Airline Leader 53 (2020): 6.

10 Kevin Michaels, “Why Business Travel Could Change Forever,” Aviation Week and Space Technology, January 18, 2021; Doug Cameron and Eric Morath, “Covid-19’s Blow to Business Travel Is Expected to Last for Years,” Wall Street Journal, January 17, 2021.

11 The author worked at the United States Railway Association, which was established by Congress to handle the reorganization of the Penn Central (at the time the largest corporate bankruptcy in world history) and other eastern railroads. The restructuring process took nearly a decade but successfully reestablished efficient and profitable freight railroad services.

12 Mary Schlangenstein, “American Air CEO Says Bankruptcy Is an Option He Won’t Consider,” Bloomberg, May 27, 2020.

13 Joe Rennison, “United Throws ‘Kitchen Sink’ at Investors to Secure $3bn Borrowing,” Financial Times, October 20, 2020.

14 United claimed their spun-off frequent flyer program would have a standalone value of $22 billion (versus a market cap for the entire airline and frequent flyer program of $10 billion at the time); Delta claimed theirs was worth $26 billion (versus a total combined market cap of $20 billion), while American claimed a valuation range of $18–30 billion (versus a combined $7 billion market cap). Hubert Horan, “The Airline Industry Collapse Part 2—Can Collateralizing Frequent Flyer Programs Help Save the US Airlines?,” Naked Capitalism, July 6, 2020.

15 Although hoarding cash on corporate balance sheets is legitimately criticized in some sectors, levering up to fund cash payouts to shareholders—which create no offsetting assets or operating improvements—was bound to exacerbate the next crisis in the inherently cyclical airline industry.

16 The details of the airline stock buybacks and the executive compensation tied to them are laid out at Ben Hunt, “Do the Right Thing,” Epsilon Theory, March 19, 2020. Many companies are guilty of more extreme value-extractive self-dealing than these airlines (Boeing is an especially egregious example). It will be very difficult for any restructuring effort that ignores these issues to succeed.

17 Hubert Horan, “The Airline Industry Collapse Part 3—Recovery Expectations Were Always Dreadfully Wrong,” Naked Capitalism, August 4, 2020; Judson Rollins, “An Economic Crisis on Top of a Medical One: Why Airline Traffic Won’t Fully Recover until the Mid-Late 2020s,” Leeham News, July 13, 2020. Rollins cited twelve forecasts from major airlines, Boeing, Airbus, and industry financial analysts and trade groups. None of the industry forecasts contemplated second or third infection spikes or long-term border closures, although by the fall estimated “full recovery” dates started gradually getting pushed back beyond 2022–23.

18 Rusty Guinn, “Hook, Line, and Sinker,” Epsilon Theory, October 1, 2020. Guinn cites multiple examples of media stories that fully accepted the industry narrative, conflating “survival of the airline” with “survival of current executives and ownership positions.”

19 David Slotnick, “Southwest Is Turning Down $2.8 Billion in cares Act Aid to Avoid the Federal Government’s ‘Onerous’ Conditions,” Business Insider, August 21, 2020; Kyle Arnold, “Airlines Have Given Up on 2020. Now Next Year Is Looking Bleak Too,” Dallas Morning News, October 16, 2020.

20 David Slotnick, “United’s CEO Argued It’s Not a Problem That Airlines Will Keep Burning Tens of Millions of Cash per Day for Months,” Business Insider, October 15, 2020; Justin Bachman, “United Airlines Sinks as Loss Undermines Vow to ‘Lead the Rebound,’” Bloomberg, October 15, 2020.

21 The three historical charts use data (limited to passenger airlines) from the Department of Transportation (DOT) Form 41. The cost efficiency chart track changes in real CASM (cost per available seat mile, the standard industry measure of unit costs, in 2019 cents) while the pricing chart shows changes in real revenue per ASM (also in 2019 cents.) The international sector in figure 2 would be twice as large if one included the U.S. service of non-U.S. airlines.

22 Figure 3 understates regional airline capacity prior to 1992 because of DOT data reporting limitations. The practice of regional airlines codesharing with legacy airlines was pioneered by Allegheny Airlines 1965, but regionals did not become an integral part of the legacy hub networks and business models until after deregulation. Regional airlines allowed legacy airlines to arbitrage their labor contracts, outsourcing part of their networks to companies that paid their employees less.

23 The LCC business model originated with PSA’s intra-California services, and was directly copied by Southwest, which began intra-Texas service in 1971; intrastate airlines had been exempted from CAB regulations. LCC data in the charts includes Alaskan and Hawaiian carriers.

24 Carriers do not report those passenger payments as “passenger revenue.” For decades, “total revenue” had run ~11 percent higher than reported “passenger revenue,” with the difference being mail, belly cargo, and excess baggage charges. Today’s higher difference (36 percent) is due to the new legacy passenger fees.

25 Thomas McCraw, Prophets of Regulation (Cambridge: Belknap, 1984), 263.

26 A full Northwest chapter 11 filing had been delivered to the bankruptcy court in Delaware but was pulled back the night before filing when major new funding was provided by KLM and Northwest’s largest unions. The author was directly involved with the chapter 11 filing, Northwest’s subsequent network restructuring, and led the development of its alliance with KLM. Pan Am effectively liquidated in stages, with its three valuable international networks sold to stronger carriers before its uncompetitive other routes were finally shut down.

27 The Hughes Airwest network was shut down shortly after being acquired by North Central (Republic) in 1979. National’s network was shut down after the merger with Pan Am in 1980. People Express collapsed into bankruptcy soon after acquiring Frontier. The Air Cal, PSA, and Jet America networks were shut down after being acquired by American, USAirways, and Alaska. American shut down the Reno Air operation shortly after merging. In a few cases, valuable hub assets were part of the deal (Texas International’s Houston hub, People Express’s Newark hub, Piedmont’s Charlotte hub, Western’s Salt Lake hub) but other assets were liquidated, the overall merger had negative returns, and the acquiring airline soon went bankrupt.

28 The failed operations were at Los Angeles (Delta, United, USAirways), San Jose (American), San Francisco (USAirways), Baltimore (USAirways), Washington and Boston (Northwest), Greensboro (Continental), and Raleigh-Durham (American). These were competing with much more efficient hubs (Newark, Atlanta, San Francisco) for a very limited volume of hub connecting traffic, and with Southwest, which could serve nonstop traffic at much lower cost.

29 Continental initially followed Northwest’s lead in adopting the strategic focus that drove the industry’s mid-’90s profit rebound, but fell off the capacity discipline wagon after Gordon Bethune, a former Boeing sales executive, became CEO in 1996.

30 The courts automatically granted any bankrupt airline the right to reject its existing labor contracts and impose the contract terms of the lowest-cost airline contract in the industry (America West at that time). In these cases, USAirways had a plausible “could not survive without these contract rejections” case, but none of the other airlines did. The author was personally involved with the post‑2002 bankruptcy cases at United, USAir, Hawaiian, ATA, and American.

31 American was the only Legacy carrier that had not gone through bankruptcy prior to 2007. American was led at that time by Gerald Arpey who was determined to protect his shareholders, but Arpey was sacked in 2011 for his failure to have exploited the labor impairments that gave its competitors an important cost advantage. See Phil Milford, Mary Schlangenstein, and David McLaughlin, “American Airlines Parent AMR Files Bankruptcy,” Bloomberg, November 29, 2011.

32 American, under Horton, prepared a reorganization plan that claimed it could match Delta and United’s profitability on a standalone basis despite being one-third smaller. Horton had agreed to massive new purchases from Airbus and Boeing in return for their support for allowing the debtor exclusive control of reorganization (and sizeable shareholdings) that Tilton achieved at United. Once American emerged, Horton’s actual plan was to eliminate the scale/network disadvantage by acquiring USAirways at an extremely low price, just as Delta had done with Northwest. This plan was thwarted by USAirways (under Doug Parker and Scott Kirby), who wanted to present a competing merger-based reorganization plan, with substantially better payments to creditors and substantially better prospects than Horton’s standalone plan. But instead of accepting the superior merger plan, Horton, Boeing, and Airbus delayed emergence for eighteen months until they got USAirways to accept excessive fleet purchases that American could not afford, and a $10 million “consulting contract” for Horton.

33 In the United States, this group includes LCCs like Southwest and leaner legacies like Continental and America West. In Europe, LCCs like Ryanair and EasyJet and rapidly growing Asian and Middle Eastern intercontinental carriers.

34 Other important elements of this story are academic corruption, and bureaucratic wars between the White House and the DOJ Antitrust Division. See Hubert Horan, “Double Marginalization and the Counter-Revolution against Liberal Airline Competition,” Transportation Law Journal 37 (2010): 251–91. This article references testimony presented to Congressional hearings on the Northwest-Delta and Continental-United mergers and testimony presented to the DOT in multiple antitrust immunity cases. Key portions of this story were summarized in a recent series of ProMarket articles: Hubert Horan, “Why Consolidation Undermined the Airline Industry’s Ability to Recover from the Coronavirus Crisis”; “The Airline Industry’s Post-2004 Consolidation Reversed 30 Years of Successful Pro-Consumer Policies”; “How Alliances Carriers Established a Permanent Cartel”; “How Airline Alliances Convinced Regulators That Collusion Reduces Prices,” ProMarket May 5, 2020.

35 Comments of Hubert Horan, “American Airlines-British Airways-Iberia et al. Joint Application for Antitrust Immunity,” Docket DOT-OST-2008-0252, March 4, 2010. The explosive growth of domestic and regional carriers after 1990 was mostly in rapidly developing markets such as China, India, and Russia.

36 All of the DOT decisions approving consolidation of the North Atlantic were explicitly based on the claim that eliminating competition automatically increases consumer welfare. For the painful details, see Horan, “Double Marginalization,” 269–76. Without this willfully fraudulent claim, none of the subsequent the mergers that reduced the U.S. legacy sector to just three players would have been possible.

37 This comparison understates the actual reduction in consumer welfare. After 2003 domestic markets continued to follow normal supply/demand dynamics, where fares are highly responsive to changes in capacity, as fares rose 15 percent because capacity had only grown 1 percent. But the increased market power in the North Atlantic allowed carriers to raise fares 46 percent even though capacity had increased 45 percent. This chart was originally published in “Statement of Hubert Horan, Proposed United-Continental Merger: Hearing Before Subcommittee of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee,” 111th Congress (2010).

38 Alison Sider, “Delta Looks toward Recovery after Dark Pandemic Winter,” Wall Street Journal, January 14, 2021.

39 These efforts are already underway. Qantas and JAL have requested increased ability to collude in a market where they already had an 86 percent market share. CAPA Centre for Aviation, “Covid-19 Crisis Strengthens Case for JAL‑Qantas Partnership,” January 6, 2021. On her last day in office, DOT Secretary Elaine Chao approved the first ever application for airline collusion in domestic markets: Leah Nylen and Stephanie Beasley, “Approval of American-JetBlue Deal Draws Warnings of Rising Airfares,” Politico, January 16, 2021.