The author thanks Lars Erik Schönander for assistance in preparing this article.

It’s Not Just NEPA: Reforming Environmental Permitting

In recent years, pandemic-related supply chain failures, oil shocks, and China’s growing dominance over critical materials has forced policymakers to reckon with the limits of free market orthodoxy. In 2018, President Trump bucked the Republican party line on trade by imposing tariffs on steel and aluminum. The Biden administration has made “Build Back Better” the centerpiece of its economic agenda, pouring massive investments into American industry with the chips and Inflation Reduction Acts.

As the focus on domestic industry has grown, so too has awareness of America’s prohibitive regulatory environment—and in particular its environmental laws. As Robinson Meyer writes in Heatmap, “For the first time in decades, both parties want something to change about the country’s permitting process.” Democrats, on the one hand, have realized that environmental review stands in the way of their climate agenda, creating years of regulatory drag for new energy infrastructure. Republicans, meanwhile, have long regarded America’s environmental laws as duplicative, easily politicized, and unreasonably stringent. With growing bipartisan interest in regulatory reform, this last year has seen a number of permitting bills introduced by both parties, from House Republicans’ Lower Energy Costs Act to Democratic senator Tom Carper’s PEER Act.

These proposals are certainly a promising start. But to call them an “overhaul” of the nation’s permitting process, as many outlets have done, is to miss the mark.

Over the last decade, critiques of environmental review have been almost singularly focused on the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA. This isn’t totally surprising: NEPA review has been responsible for slowing down everything from energy infrastructure to highway bridges to congestion pricing plans. Its modern interpretation has also made it particularly frustrating for proponents of industrial policy, as NEPA is triggered by “virtually every federal action”—meaning that infrastructure projects often have to undergo NEPA as a result of government support. For all of these reasons, NEPA surely needs reform.

But NEPA is just one of a patchwork of environmental laws that impact industry in the United States. Several other fifty-year-old statutes—the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, the Clean Water Act, and above all the 1970 Clean Air Act—play an enormous role in dictating manufacturing firms’ decisions. Indeed, in 2017, the Department of Commerce reached out to manufacturing stakeholders about the greatest regulatory barriers to development. The resulting report found that a provision of the Clean Water Act was the most commonly cited barrier, with two Clean Air Act provisions—New Source Performance Standards and New Source Review—rounding out the top three. NEPA didn’t even make the top ten.

Restoring American manufacturing, then, will demand that we look beyond NEPA to the many other environmental laws affecting industry in this country. These, too, will need reform.

A Case Study in Chips

Nowhere is the need for reshoring more critical than the semiconductor sector. Semiconductors are the lifeblood of the industrial world. Just about every electronic system—phones, cars, military defense—relies on the technology, with manufacturers shipping over a trillion semiconductor units last year alone. But despite semiconductors’ ubiquity throughout the modern economy, their production takes place in just a few places. The majority of semiconductor “fabs” (microchip fabrication plants) are located in just four east Asian countries. Over 90 percent of the world’s most advanced semiconductors are manufactured by just one firm: Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC).

This dependency represents a serious national security risk—for there’s a possibility that China will attack Taiwan within the next decade. If it does, the United States could lose access to much of the world’s cutting-edge chip supply overnight.

It wasn’t always this way. American firms developed the first integrated circuit in 1959, and proceeded to dominate the market for the next twenty-five years. Even in 1990, over a decade after the arrival of Japanese competition, America controlled 37 percent of global production capacity. That number has fallen to 12 percent as of 2021. What happened? Much of this decline was due to environmental review.

One of the central principles driving the semiconductor industry is Moore’s Law. Named for Intel cofounder Gordon Moore, the law states that the number of transistors on microchips will double every two years—and that computational power will therefore increase rapidly over time. Simply put: innovation happens extraordinarily quickly. As a result, one of the crucial considerations for semiconductor manufacturers is how quickly they can build and modify new fabs. The ability to move just a few months faster than one’s competitors means that firms can produce substantially more advanced chips, and be the first to bring them to market.

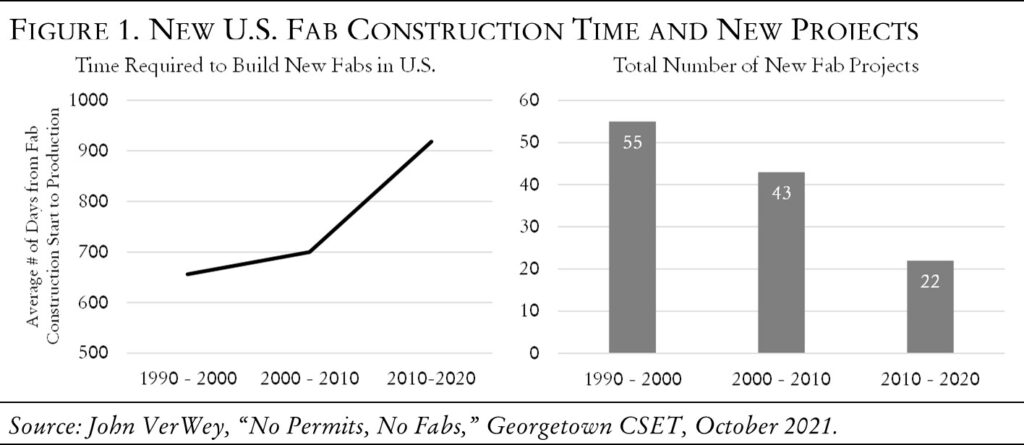

As it would happen, there are few countries worse for this than the United States. From 1990 to 2000, it took an average of 736 days for a U.S. fab to be built—longer than anywhere else on the planet except for southeast Asia. That number has been increasing, too—between 2010 and 2020, the time required to build a new fab in the United States rose to over 900 days. In Asia, meanwhile, construction timelines have been in decline over the last decade, falling from 703 to 642 days in Taiwan, and from 747 to 675 days in China.

There are a number of reasons for this. In Taiwan, for example, the government provides significant logistical support to new fabs in an effort to attract foreign investment. Singapore has established several plots of land for semiconductor manufacturers that come pre-equipped with power, electricity, and roads. But above all, the ballooning construction timelines in the United States are the result of its own regulatory environment—and in particular, the Clean Air Act.

Where We Started

The Clean Air Act was born out of a period of immense economic growth and environmental degradation. The first half of the twentieth century saw the arrival of U.S. Steel and the automobile assembly line. The American manufacturing sector boomed. At the same time, factories, unburdened by environmental regulations, dumped their sludge into nearby rivers, poisoning the waterways. Power plants spewed toxic pollutants into the atmosphere, triggering a series of lethal smog events that would claim the lives of hundreds and cause illness for thousands more.

By the late 1960s, these disasters had become frequent enough that Congress started to recognize the need for more robust environmental protections. Over the next decade, it passed three of the most far-reaching environmental laws in the nation’s history—NEPA, the Clean Air Act, and the Clean Water Act.

Today, the Clean Air Act has become the cornerstone of U.S. environmental policy. As Richard Schmalensee and Robert Stavins write in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, the Clean Air Act “was the first environmental law to give the Federal government a serious regulatory role . . . and became a model for subsequent environmental laws in the United States and globally.”

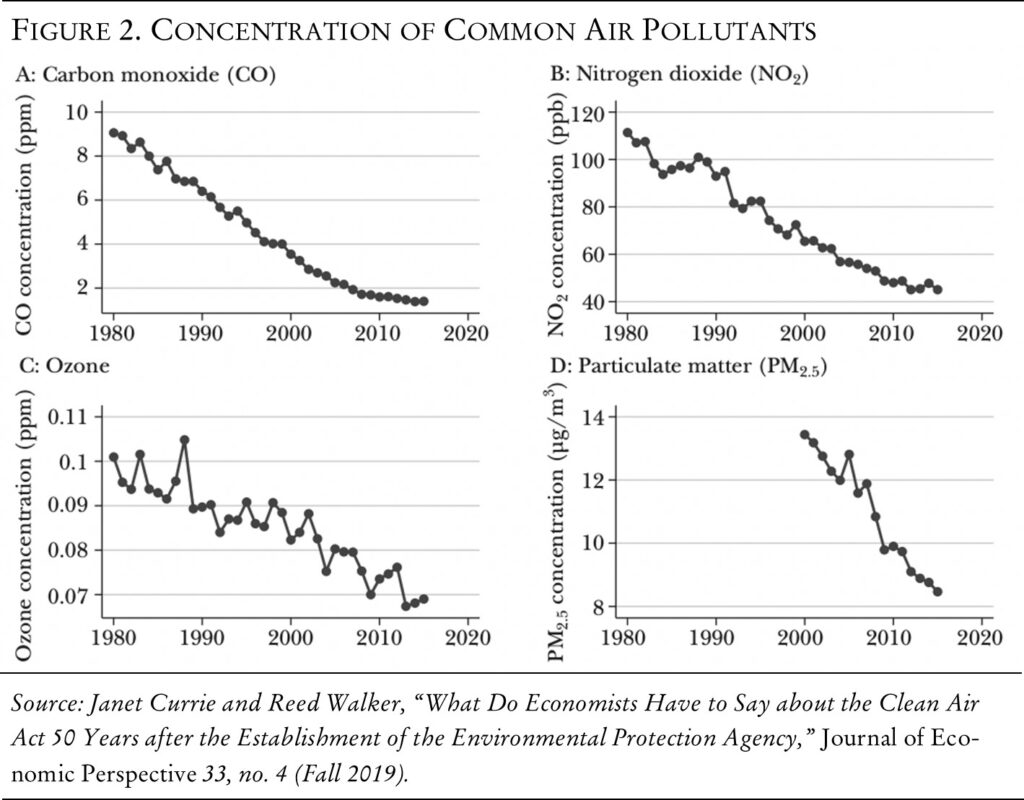

The law has been profoundly effective at reducing air pollution across the country, causing the six most common pollutants to drop by an average of 69 percent between 1980 and 2019. The Environmental Protection Agency’s efforts in this area have been estimated to prevent over two hundred thousand premature deaths each year.

At the same time, the law, and the way that it has been implemented over the decades, has many flaws. Its excellent environmental record means that few are willing to point this out. But the Clean Air Act today is the greatest regulatory barrier to manufacturing in the United States. In an increasingly multipolar world, it is no longer an option to look the other way.

This tension between environmental protections and economic development presents a challenge for those pursuing any sort of reform. Any critique of even small elements of the Clean Air Act will inevitably run into fierce resistance from those who view “reform” as code for reduced safety measures and crony business interests. But many of the solutions to the Clean Air Act’s problems will not come in the form of deregulation per se, but rather through regulatory innovation—new frameworks and restructurings of existing rules that will improve efficiency without narrowing the law’s substantive environmental protections. That is, done right, Clean Air Act reform will better align environmental and economic imperatives, not suppress one in favor of the other.

The Clean Air Act Today

The Clean Air Act covers six “criteria” pollutants: particulate matter, ozone, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, and lead. For each of these pollutants, the Act tasks the EPA with setting National Ambient Air Quality Standards (naaqs)—a standard that defines the maximum amount of a pollutant that can be in the air without harming public health.

Using the naaqs as a benchmark for acceptable pollution levels, the EPA is responsible for regulating major stationary sources of pollution, or “major sources.” In areas with pollution levels that meet the naaqs requirements (known as “attainment” areas), major sources must be able to demonstrate that they will stay below the “increment”—a measure of allowable air quality deterioration—in order to receive a construction permit. Meanwhile, in “nonattainment” areas, sources must comply with the Lowest Achievable Emissions Rate (LAER). LAER represents the most stringent emission limitation that can be achieved and, crucially, does not take cost into consideration.

Regardless of attainment status, all new major stationary sources must apply for an air permit prior to construction, and again for any major modifications they make to their facility. This entire preconstruction permitting program is known as New Source Review (NSR) and is the mainstay of Clean Air Act regulation.

The NSR permit application process consists of up to six steps. Each one has the potential to create substantial cost and time overruns. These steps include preparation of the permit application and participation in any associated pre-permit application meetings, issuance of a permit application completeness determination by the state, development and negotiation of the draft permit, opportunity for public notice and comment on the draft permit, response of permitting authority to public comments, and administrative and judicial appeals.

Application preparation alone represents an enormous hurdle for manufacturers. Sources often have to spend years on engineering, design, and assessment studies prior to actually submitting an application. As the Air Permitting Forum reports, “Even under optimistic conditions, it can take at least two years from the beginning of the frontend engineering work until public notice of the draft permit is published.”

Once a permit application has been submitted, the Clean Air Act requires the EPA to either grant or deny the permit within a year. There is, however, no practical way to enforce this. A 2015 report from Resources for the Future found that the nationwide average time to obtain an NSR permit for coal- and natural-gas-fired electric generating units was roughly fourteen months. In other words, the EPA exceeding the set permitting time limit is not the exception—it’s the rule.

Adding to all of this is the fact that Clean Air Act regulation typically involves overlapping federal, state, and even local jurisdictions. In general, Clean Air Act permitting is handled by the states. But states must develop a state implementation plan (SIP)—a comprehensive plan for how to achieve national ambient air quality standards—for the EPA to sign off on. And even after approving the SIP, the EPA still retains authority over air quality modeling, and may choose to wade in on the state’s permitting process at any time.

In 1992, for example, the EPA signed off on Texas’s SIP. Two years later, Texas submitted a proposed amendment to the SIP that included a “Flexible Permit” program, designed to set a single emissions cap for each plant rather than setting limits for each individual polluting source. The idea was that this would provide greater operational flexibility to manufacturers, allowing them to make equipment changes so long as they didn’t exceed the set emissions limit. But in 2010—sixteen years after Texas proposed the change—the EPA announced its final disapproval of the program, leaving approximately 140 permitted facilities vulnerable to federal enforcement and fines.

Complicating matters further is that states may also delegate permitting authority to their counties. In some cases, a state will delegate authority to some counties, but not others. In other cases, states will create air-permitting “districts”—typically a group of neighboring counties—and split up jurisdiction among them.

This has caused significant discrepancies in what the permitting process looks like around the country. Indeed, the Clean Air Act functions as a “floor, not a ceiling,” meaning that states, counties, and other regions with original permitting jurisdiction may implement substantially tougher air regulations than federal law requires. As a result, permitting timelines vary massively depending on location. Between 2002 and 2014, for example, the permit processing time for natural gas units ranged from seven months in EPA Region 7 (Iowa, Kansas, Mississippi, and Nebraska) to nineteen months in EPA Region 9 (California, Arizona, and Nevada).

Federalism and State Capacity

Some of this regional variation may be attributable to the country’s political polarization. It is easy to see, for example, that the more Republican EPA regions generally have faster permitting times than Democratic ones.

But the bigger issue—and indeed the issue that has driven America’s permitting problems more broadly—is the lack of state capacity in both Democratic and Republican states. Our state agencies are generally under-resourced—in financial capital, human capital, and often both. As one former EPA executive explained to me, states rarely have enough staffers capable of sifting through the Clean Air Act’s highly technical permitting documents. This alone drives a great number of delays in the NSR process. But even more importantly, the lack of resources within state agencies means that permitting offices are seldom able to take full advantage of their authority to develop new permitting strategies.

One of the most commonly cited problems with New Source Review, for example, is “new source bias.” That is, the structure of NSR is such that it regulates new sources and new major modifications, but has little impact on existing facilities. This creates a number of attendant environmental and economic problems.

As Richard Revesz and Jack Lienke explain in Regulatory Review, “Pairing restrictive standards for new sources with either lax standards or no standards at all for existing sources creates two problematic incentives: Old plants are encouraged to stay in business longer than they otherwise would, and new plants are discouraged from coming online altogether.” In other words, new source bias means that it is sometimes more economic for facilities to continue to operate more inefficient, higher-polluting equipment than to replace them with better pollution-control technology.

One solution to this is flexible permitting. Flexible permits began as an experiment in the 1990s, when the increased competition in global manufacturing led several industries to approach the EPA about “friction” in the Clean Air Act permitting process. In response, the EPA and state authorities launched an effort to increase operational flexibility without reducing environmental protections. The result was several flexible-permit pilot programs. Each permit varied slightly in scope, but the basic concept was the same: rather than requiring facilities to fill out a permit modification for every single change they made to their facility, the flexible permits either set a cap on the source’s overall emissions—allowing sources flexibility so long as they stayed below that cap—or preapproved certain types of modifications. One such permit was issued to the Intel semiconductor fab in Aloha, Oregon.

The Aloha program was a smashing success. In the five years that Intel had a flexible permit, the Aloha facility reduced its actual emissions of volatile organic compounds by over 70 percent. Intel was also able to make between 150 and 200 operational changes a year without having to undergo NSR permitting. A 2002 EPA evaluation of the program noted, “This number of changes, combined with the Oregon DEQ approval time frame of up to 60 days per change, suggest that there would likely have been significant delay under a conventional permit,” and further added that, “Industry estimates of the opportunity costs of production downtime and time delays run as high as several million dollars in just a few days.” Most important of all, Intel suggested that the flexible permit was the difference between continuing to invest in the Oregon facility and redirecting investment and operations to locations (potentially abroad) where changes could be more readily accommodated.

All told, EPA found that Intel’s pilot permit delivered substantial environmental benefits, operational flexibility, and clarity for state regulators throughout the permitting process. One might reasonably assume, then, that flexible permits would become ubiquitous in the decades since the EPA pilot programs. But that’s not what happened.

States have authority to develop flexible permitting programs, but as we’ve seen in the case of Texas, this often takes a great deal of time, money, and know-how to design a program that is Clean Air Act compliant. At the same time, many states have made tweaks to the language of flexible permits that put a significant dent in their overall appeal.

The New York Department of Environmental Conservation, for example, has a provision allowing for a type of flexible permit called a plantwide applicability limit (PAL) permit to be issued. PALs are clearly defined by the EPA as an acceptable permitting approach, and are designed to be attractive to facilities that make frequent equipment changes. But the New York Department of Environmental Conservation has an additional requirement on top of the existing PAL guidelines: after five years, the PAL must be reduced to 75 percent of its initial emission cap unless the owner of the facility can demonstrate that such a reduction in emissions would be impossible with the best available control technology. This has created a great deal of uncertainty for permitted sources, who often cannot predict whether they will have the resources five years down the line to upgrade their existing pollution‑control equipment. As a result, not a single facility in New York state has applied for a PAL in the first place. Other states, such as Vermont, never wrote PALs into their state implementation plan at all. In these jurisdictions, PALs are simply not an option.

So while the EPA officially promulgated PALs in 2002 as a widely available flexible permitting mechanism, the reality on the ground has been very different. All told, between 2002 and 2020, PALs were issued to only approximately seventy facilities spanning twenty states across the country. The clearest strategy for reducing regulatory friction under the Clean Air Act has seen barely any uptake.

The absence of PALs in most jurisdictions has had a compounding effect on their unpopularity. As environmental consulting firm ALL4 points out, “Due to the relative scarcity of PAL permits, it is fair to assume that many agency personnel have never seen a PAL application. The learning curve associated with agency review of a PAL application will likely translate into an extended technical review period.”

In my conversations with industry players, the EPA, and state permitting authorities, this lack of expertise was consistently cited as a major concern. NSR in general is a regulation written to cover every conceivable type of industry. Its implementation is largely left to guidance and policy that changes with administrations. States simply don’t have the resources, or know-how, to keep up.

On the other hand, the lack of data around flexible permits has limited companies’ interest in investigating their potential benefits. “There’s an old Yogi Berra line about a popular restaurant that goes, ‘Nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded,’” one former career EPA official told me. “This is the opposite: Facilities don’t think [PALs] are useful, so they don’t apply for them. And then they say, ‘See, PALs aren’t useful, because nobody is applying for them.’” For regulated sources, PALs may look like an extension of—not a solution to—the problems posed by under-resourced permitting authorities.

Minor Sources

States are not just required to regulate major sources—that is, facilities that have the potential to emit more than one hundred tonnes per year of one of the Clean Air Act’s six criteria pollutants. They’re also required to comply with national ambient air quality standards. This means that there are many polluting sources which do not meet the “major” threshold, but do contribute to air quality deterioration. States are tasked with developing their own programs to regulate these “minor” sources, too.

State capacity is a problem here as well. Minor sources, like major sources, must undergo review when they make modifications to their facility. While this review is typically less stringent than Major New Source Review, it nonetheless imposes significant administrative costs and time considerations on facilities. The Maricopa County Air Quality Department, for example, allows itself up to nine months to permit a minor source.

Most states, including those that offer PALs, do not have flexible permitting programs for minor sources. And so despite the fact that minor sources are lesser polluters than major sources, there are often more flexible permitting options on the table for the higher pollution facilities.

States could develop flexible options for their minor sources if they wanted to, and a few, like Idaho and Texas, have. But unlike with major sources, there is no federal-level guidance from the EPA around how to go about doing this. The entire discussion of state Minor NSR in the Code of Federal Regulations spans just a few pages, and says nothing of flexible permitting.

While industry stakeholders could always pressure state permitting authorities to develop flexible permitting programs for minor sources, there is plenty of incentive to resist this sort of regulatory innovation. Developing a new permitting program—and in particular a flexible permitting program—can require a great deal of resources. The complexity and novelty of flexible permits creates substantial uncertainty among stakeholders and environmental groups, which can in turn lead to litigation. And because Minor NSR is part of states’ implementation plans, new flexible permit programs must receive EPA approval, bloating the process even further.

The lack of flexibility in minor source permitting is not a secondary concern. There are, after all, far more minor sources throughout the country than major sources. And so effective Clean Air Act reform will not just require federal-level initiatives like PAL permits—it will also require significant state-level action.

Our Broken Information Systems

The final, and perhaps most essential, problem with the Clean Air Act’s federalist approach is that it is difficult to make any generalizations about how the permitting process actually works nationwide. Just getting access to the data alone is often a heavy lift. For NEPA, the EPA keeps a national dashboard of every environmental impact statement generated under the act. There is no equivalent for the Clean Air Act.

In an effort to get a snapshot of what permitting looks like around the country, I submitted records requests for all of the permitting paperwork associated with sixteen different semiconductor facilities across ten air quality departments in eight different states.

The results varied dramatically. Maricopa County (home to Intel, NXP Semiconductor, and Microchip plants) had recently digitized many of their public records, making it easy to sift through much of the paperwork associated with each facility. Intel’s is the largest facility in the region, and has over six thousand pages of publicly accessible permitting paperwork. NXP, a much smaller plant, has about three thousand pages dating back to 1995.

But even in Maricopa, the full permitting picture is blurry. When I called up the Maricopa County Air Quality Public Records office to ask what percentage of the total permitting paperwork was available online, the representative said he thought it was “98 percent, 99 percent,” but that that was only an estimate.

Similar issues followed in Texas. The massive Samsung facility in Austin had just short of nine thousand pages of permitting paperwork available online, but was missing thirty permits due to their containing “confidential information.” In California, Virginia, and Utah, public records requests returned mostly incomplete paperwork, generally consisting of just the applications and permits themselves, rather than all of the associated modeling, technical support documents, and public notices.

Finally, in Oregon, where air permits have not yet been digitized, I was initially told that fulfilling the records request would be impossible, as the total number of pages was approaching fifty thousand. I asked them to provide us with a cost estimate for fulfilling the request anyway—and two weeks later, received an invoice for the paperwork associated with the Intel Oregon facility. The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality estimated there was a total of 100,000 pages of permitting paperwork, and calculated that it would cost $7,600 (seven cents per page, plus $600 for staff time) to get them scanned and sent over.

All of these are just a few examples of a larger data problem in the United States. As economist Samuel Hammond recently noted, “The firmware of the US government is 70+ years old. We validate people’s identity with a nine digit numbering system created in 1936. . . . The IRS Master File runs on assembly from the 1960s.” Indeed, our information systems are often decades out of date, forcing policymakers to design solutions with an incomplete picture of what the problem actually looks like. Clean Air Act permitting is no different.

Getting a Clearer Picture

Effective, wide-ranging regulatory reform will not be possible until the United States improves its collection and distribution of data. It can no longer be acceptable for public records to be broadly inaccessible, filed away in state office cabinets or stored on agency hard drives. Efforts to improve the Clean Air Act must start here.

There have been a few related bills passed at the federal level. The 2014 DATA Act, for example, established standards for and expanded the scope of financial data that federal agencies have to provide to a central government website. The Evidence Act of 2018 required agencies to make federal data publicly available by default, and to create a searchable catalogue of all of their datasets. Both of these laws are relatively new, by bureaucratic standards, so it remains to be seen how effective they will be at driving data modernization over the long term. But there has been real success at the margins—the Department of Health and Human Services has released a comprehensive data inventory on HealthData.gov, while the Department of Commerce has steadily increased the availability of its economic and census data sets.

When it comes to the Clean Air Act, there must be similar policies implemented at the state level. Ideally, Congress would pass legislation setting common standards and terminologies for Clean Air Act data collection, processing, and reporting across all jurisdictions. This would include a requirement for all environmental data to be provided in machine-readable formats and would charge state governments with establishing their own open data platforms.

Upgrading data management infrastructure, training personnel, and building capacity will require substantial resources. Authorization for funding these programs should come from Congress, but in lieu of congressional action, the executive branch could also direct funds toward such initiatives. Blunt-tool policy approaches like grant giving are obviously imperfect—but enough jurisdictions have successfully digitized their permitting documents, demonstrating that such upgrades do become possible with sufficient resources. It’s worth the cost.

At the very least, state and local permitting authorities ought to change their recordkeeping conditions and practices going forward. Perhaps it’s too heavy of a lift to digitize the last two decades of public documents, but there is little reason that these authorities cannot make electronic, publicly accessible copies of the permitting documents they produce in the future.

The implications here extend far beyond the Clean Air Act, of course. So many tractable policy problems in this country have been obscured by the decentralization of public data. And in an ideal world, the United States would start improving our data collection processes tomorrow. But modernizing our information systems will, realistically, take years. In the meantime, there are a number of reforms that, even without a perfectly clear picture of Clean Air Act permitting across the country, can clearly bring benefits to the American manufacturing sector.

What Can Be Done

There is always the possibility that Congress moves to amend the Clean Air Act, in which case the scope of potential reforms would be substantially broader than many of those included here. But this is unlikely to become a political reality in the near future. There is no coalition pushing for Clean Air Act reform in the way that there is for NEPA. Therefore, the following recommendations are those that are possible within the existing legal landscape.

The most obvious of these is the greater use of flexible permits. There are currently two key barriers standing in the way. First, states such as New York can and often do add additional stringency to PAL permitting language, discouraging regulated facilities from applying in the first place. Second, many states do not write PALs into their state implementation plans at all, making PAL use impossible.

As a first step, the EPA should issue guidance expressing disappointment in the lack of PAL uptake. This may sound toothless—and it is perhaps not enough on its own to move the ball forward—but EPA guidance really does impact the way that laws are implemented. Particularly when it comes to complex issues in which states lack expertise, state authorities often look to guidance for help designing their own environmental policies. For jurisdictions looking to spur industrial development, guidance favoring PALs will help direct policymakers in the right direction.

Outside of EPA guidance, most of the responsibility for PAL uptake will fall to the states. Crucially, state legislatures have the power to direct state agencies (in this case, departments of environmental quality) to incorporate specific elements into their regulatory frameworks. This includes the integration of PALs into state implementation plans.

State legislatures should also be involved in aggressive oversight of their permitting authorities. In states that include PALs in their SIPs but have low or no PAL uptake, authorities should be tasked with explaining this discrepancy. When state agencies add additional layers of regulatory language on top of the federal baseline, they should be able to justify why the addition is necessary. If they cannot, state legislators should block the proposed regulation or require modifications.

Despite the gridlock around Clean Air Act reform at the federal level, there is good reason to think that effective state-level action is possible. This is particularly true in red states, which often want to reduce regulatory restrictions but have historically lacked the expertise to design solutions. But even in more liberal jurisdictions, PALs are not necessarily unpopular—they’re just unknown. Arizona, a left-leaning swing state, awarded a PAL to the Intel Chandler semiconductor facility with little pushback. One of the early flexible permit pilot programs took place in Oregon, not exactly a bastion of conservative politics. There is real potential for successful state legislation to this end, should legislators make it a priority.

Another obvious opportunity for state action is around Minor NSR. Just as states should make use of PALs for major sources, they can likewise develop flexible permit options for minor facilities. And unlike with Major NSR, states have substantial latitude in designing minor source programs.

The EPA can help this process along by allocating funds toward the development of Minor NSR programs. Wherever possible, they should also provide expertise to states that may lack the know-how to develop such programs from scratch. If state authorities do not move to develop flexible Minor NSR permits of their own volition, state legislatures should require them to do so.

Conversely, states should apply more pressure on the EPA when the agency drags its feet reviewing changes to their state implementation plans. In theory, Section 110(k)(2) of the Clean Air Act requires the EPA to approve or deny revisions to state implementation plans within twelve months. Similar to the twelve-month timeline for NSR permitting, however, the EPA often takes quite a bit longer. There are frustratingly few solutions to this problem outside of amending the Clean Air Act—but in some cases, like the EPA’s sixteen-year delay in ruling on the Texas flexible permit program, lawsuits should be seriously considered. If there does happen to be an opportunity for congressional action, one straightforward option is to provide for “default approval”; if the EPA does not issue approval or rejection within a certain timeline, the SIP revision should automatically go through.

What’s more, the EPA has historically taken a very narrow view of the sort of operations that can occur before a facility receives its construction permit. There is little reason that the EPA cannot expand the scope of acceptable pre-permit construction. Indeed, facilities generally will not emit any regulated Clean Air Act pollutants until they actually begin production. Why not allow facilities to take on the investment risk that their permit application will be declined, and begin construction while waiting to receive the regulatory green light? It is a simple tweak, and one well within the EPA’s purview, that has the potential to make a substantial impact on development timelines. It takes two and a half years for a semiconductor fab to get built in this country. Allowing this process to run concurrently with permitting, then, would cut as much as 50 percent of the time between permit application and the start of production.

Finally, when permitting semiconductor facilities, authorities at the state and local levels should treat the entire fab as the regulated emissions source, rather than treating each piece of fab equipment as a unique emitter. Right now, the latter approach is more common, but it’s enormously prohibitive. Semiconductor facilities must constantly swap out and replace equipment to keep up with operations. When each piece of fab equipment is treated as its own source of emissions, facilities must notify permitting authorities prior to every single change they make.

Contrast that to the Maricopa County Air Quality Department’s approach of treating the entire fab as the emissions source. Under this regulatory model, semiconductor facilities can make frequent changes within the factory without having to notify permitting authorities. This approach also makes it easier for facilities to estimate emissions. Back when Maricopa County permitting authorities treated every piece of fab equipment as an emissions source, Intel had to test every single fab tool to generate an emissions profile for the facility. Now, facilities just have to periodically test their exhaust points.

There are relatively few cases in which permitting authorities have this sort of discretion under the Clean Air Act, but what constitutes a “source” is one of them. In fact, while the Supreme Court’s famous 1984 Chevron decision is better known for its implications for agency deference, the case itself concerned this very question. With that in mind, there is no reason that more air quality departments cannot follow Maricopa County’s lead.

Looking Ahead

In my conversations with leaders in the semiconductor industry, EPA executives, environmental consultants, and permitting authorities at the state and local levels, two consistent themes emerged. First, every person I talked to acknowledged that the Clean Air Act had real problems, but none of them wanted to go on record saying as much. Clean Air Act reform remains a touchy issue, and no one wants to be the first to criticize it publicly. Second, there was a general feeling that while the Clean Air Act is indeed a major barrier to economic development, there isn’t much that can be done about it. After all, Congress hasn’t significantly amended the law in over three decades, and the Clean Air Act does not offer much room for discretion or interpretation.

On the first point, policymakers will have to play the long game, working to make the idea of Clean Air Act reform palatable over time. The renewed interest in NEPA may be a first step. Perhaps, in time, supply shocks will force the issue. Let us hope it doesn’t come to that.

On the second point, there are real reasons to be optimistic in the short term. A number of solutions could be implemented by the EPA tomorrow. There are policies that state legislatures could pass this year. These policies are not the sort of thing that gets much press coverage—but each small win can have huge ripple effects for American industry. Reducing the permitting timeline for a single semiconductor facility can save that facility millions of dollars a day. Just a few success stories can bring greater investment moving forward. The next decade will be critical for America’s role in the international order. We should not leave Clean Air Act reform by the wayside.