REVIEW ESSAY

Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling,

Why It Matters, and What To Do about It

by Richard Reeves

Brookings Institution Press, 2022, 298 pages

In Dream Hoarders (2017), Richard Reeves, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, mapped our growing class divides in income, “education, family structure, health and longevity, [and] even in civic and community life.”1 In Of Boys and Men, published last year, Reeves turns his attention to another increasingly disadvantaged group: males.2 Reeves chronicles the myriad but neglected ways in which boys are falling behind in school and men are increasingly adrift from both work and family. Notwithstanding his questionable treatment of the enduring importance of marriage for men, women, and children alike, this insightful study ought to serve as a touchstone in future debates about men’s flourishing.

Reeves is not the first center-left thinker to sound the alarm about the falling fortunes of men. In 2012, Hanna Rosin prophesied The End of Men: And the Rise of Women, arguing principally that “the modern, postindustrial economy is simply more congenial to women than to men.”3 Rosin’s book was preceded by a long series of warnings, largely but not only from the Right, about the growing precarity of boys and men, including Kay Hymowitz’s Manning Up,4 Nicholas Eberstadt’s Men without Work,5 and Christina Hoff Sommers’s The War against Boys.6 Fears over men’s prospects were voiced even late in the last century: in 1996, the Economist warned that men were “tomorrow’s second sex,” on the grounds that economic change would favor typically female interests and skills.7 Predictions of feminism-induced male collapse, meanwhile, go back at least to George Gilder’s Sexual Suicide.8

Of Boys and Men shares with these previous works the sense that much contemporary male malaise is rooted in a loss of masculine identity—long provided by traditional social and economic roles—under the pressure of women’s increasing political and economic independence. Like Rosin, Reeves rejects conservatives’ conviction that helping men must require restoring some of those now lost norms, particularly regarding marriage. Reeves does more than bring Rosin’s story up-to-date, however; where the journalist Rosin constructed a narrative of decline, Reeves, a policy analyst, offers a suite of reforms which might help to arrest it.

Its wonkishness notwithstanding, few books have plucked so many mystic chords of memory in me as Of Boys and Men. As I read, I recalled how I coasted through most of high school and attended a nonselective college, while my younger sister graduated third in her class of six hundred and went to Harvard. I thought of boys (again including me) who suffered their father’s absence in pained silence. I thought of many male friends who now, in their thirties, were never married or are divorced, mostly childless, often adrift and in dead-end jobs. How did this happen?

Achievement Gaps

Reeves follows American men down a slippery slope from education, through the labor market, to fatherhood and marriage. In schools, a yawning achievement gap has opened between girls and boys even in early grades.9 Girls now earn two-thirds of A’s in high school and enroll in more Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate classes than boys. They also graduate from high school at higher rates than boys, and make up close to 60 percent of the college population.10 The field has become so lopsided that male college applicants now enjoy robust affirmative action measures—in the form of de facto lower admissions standards—aimed at boosting their lagging matriculation rates across the country.11

Reeves fingers several potential causes for this reversal of educational fortunes between the sexes, including the dearth of male teachers and the decline in technical and vocational education. The most important factor in Reeves’s view, however, is the sexes’ different developmental profiles: girls mature more quickly than boys, maintaining a one-to-two-year head start through adolescence, not only in their intellectual development, but also in their capacity for self-regulation, delayed gratification, and other crucial social and emotional skills.12

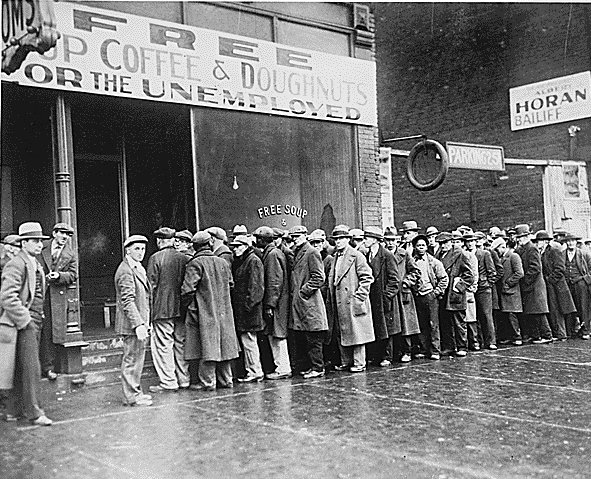

When young men (particularly the large majority of them who don’t graduate from college) enter the labor market, their problems compound. The manufacturing sector that formed the heart of the blue-collar labor force in this country for most of the twentieth century has declined by 6.7 million jobs since 1980. Traditionally “male jobs,” Reeves notes, “have been hit by a one-two punch, of automation and free trade,”13 especially the shock caused by China’s accession to the WTO in 2001. (In this book, and to a lesser extent in Dream Hoarders, Reeves neglects the role of increasing legal and illegal immigration by low-skilled workers as a key factor in driving down wages among working-class men.14) The result is that “labor force participation among men in the U.S. has dropped by 7 percentage points over the last half century, from 96 to 89%.”15

This is not the whole story, of course: there is still a pronounced “wage gap” between men and women which favors elite men who do well in the labor market. As Reeves recognizes, this gap is caused principally by the different professions chosen by men and women, and by the different choices that men and women make in how to balance work and family life. Women, for example, are more likely to take time away from work to raise young children, and more likely to return to work on a part-time basis thereafter.16

The wage gap at the very top of the income distribution notwithstanding, men’s economic position as a whole has eroded in the past half century, in the same period as women have achieved an unprecedented degree of success in the labor market. Women’s largest gains have been in what Reeves dubs the “HEAL” professions, focused on health, education, administration, and literacy more broadly17—professions which men are leaving and increasingly avoid. (I suspect that this clever acronym will be Of Boys and Men’s most enduring legacy, although if the anonymous ubiquity of Judith Ramaley’s “STEM” is any guide, Reeves himself is, alas, not likely to receive due credit for it.18) This growing mismatch between men and women’s economic prospects poses a further challenge for men, in that they have become increasingly “unmarriageable,” because women remain stubbornly averse to marrying a man who cannot at least match her ability to provide for a family.19

And the cycle threatens to become vicious. Bachelors are more likely than their married peers to lack the recognizable cultural script that has long given meaning and purpose to men’s lives. As Reeves rightly notes, “for at least the last few thousand years, men could essentially describe their role in four words: ‘providing for my family.’”20 Married men, he notes, are generally happier, healthier, and longer-lived than their unmarried or divorced counterparts.21 This has much to do with the fact that marriage (and especially monogamy, which, unlike polygamy, takes men “off the sexual market”) and fatherhood act as a “testosterone suppression system,” reducing the supply of the hormone that makes men so disproportionately amorous, violent, and risk-prone.22

That script has broken down, Reeves suggests, as men have increasingly struggled either to secure work that would allow them to fill that role, or to find wives interested in what some women have come to see as “a relationship of crippling dependency.”23 And since, in most societies, fathers’ relationships with their children are mediated by mothers, this has increasingly cut fathers off from their children as well, whose conception and nurture are now viewed by many men and women alike as having no essential connection to marriage.

Reeves stresses that all of the problems facing men and boys are especially pronounced among lower-class and black Americans. Or, put another way, the considerable challenges facing lower-class and black Americans fall disproportionately upon men. For instance, less-educated Americans have borne the brunt of an epidemic of “deaths of despair”—deaths from suicide, alcohol poisoning, and drug overdose—but, Reeves notes, three-quarters of those deaths have been among men.24 Further compounding the plight of marginalized men is the fact that, as Reeves shows in the book’s most surprising chapter, many social programs aimed at improving the lot of the needy—from tuition subsidies to life coaching—have no average effect on men at all.25 A great deal of welfare spending does not help the Americans falling fastest and farthest behind.

Before Reeves turns to policy recommendations, he devotes a chapter apiece to progressives’ and conservatives’ respective confusions regarding the plight of men. Progressives, in his telling, shy away from attending to the issue at all, treating any solicitude for men as an implicit threat to women’s political and economic equality.26 They also refuse to acknowledge the real biological basis for ongoing differences between men and women, treating any and every disparity in the workplace or at home as evidence of sex discrimination.27 Reeves is impatient with this line of thinking, rightly insisting that we have nothing to fear from the fact that software engineers and CEOs are more likely to be men, and that kindergarten teachers and stay-at-home parents are more likely to be women.28 Indeed, the very fact that these are average differences means that there will be nontrivial numbers of women who love to code and men who would thrive as early-years educators.

If progressives neglect the plight of men and undervalue nature, conservatives, in Reeves’s telling, make the opposite errors. The Right seizes on male struggles to argue for the need to reverse many feminist gains—to “make women dependent again in order to resupply men with purpose”29—and tends to use natural preferences as a justification for every economic disparity between men and women.30 Reeves is rightly skeptical about this monocausal story, which is essentially the mirror image of the progressive’s relentless appeal to sexism. He cites one paper which concluded that the sex disparities in professions such as engineering (11 percent women) and “medical services” (75 percent women) were substantially wider than would be predicted “if [reported] interests alone were driving occupational choice.”31 In short, nature matters a great deal for explaining sex differences in occupational sorting, even if it isn’t the only factor.

Policy Solutions

Reeves concludes with a series of ambitious policy proposals, including a number of interrelated reforms to education and labor policy. He argues, first, that if boys have fallen behind girls in school largely because of differences in each sex’s maturation (importantly, for Reeves, boys’ cerebral cortex matures much later), then we need to “red-shirt” them, starting boys in school a year later than girls. They will then be better able to match their female peers’ intellectual and emotional maturity.32 This would be a radical reform to public education, even considering Reeves’s proposed gradual phase-in, but it strikes me as eminently worth pursuing, at least in pilot form.

Less revolutionary but still important are Reeves’s proposals to recruit many more male teachers33 and to expand “career and technical education” (CTE) in high schools, community colleges, and apprenticeships, in all of which the United States lags far behind other developed countries.34 Nonetheless, I found myself wondering where the graduates of Reeves’s expanded CTE programs could be expected to work—a community only needs so many electricians and plumbers, after all. Unless we make a concerted effort, through reforms to trade and industrial policy, to revive American manufacturing, CTE could ultimately prove a bridge to nowhere.35

Finally, Reeves argues for well-funded efforts to attract more men into HEAL professions, notably healthcare and education. Unlike manufacturing, these sectors are growing right now, and many are facing acute labor shortages, even as they draw new employees largely from just (the female) half of the population. Reeves proposes creating college scholarships earmarked for drawing men to nursing or teaching,36 but also initiatives aimed at “getting more boys and young men thinking about HEAL careers early.”37 Beyond proposals for better messaging, however, Reeves’s account is surprisingly short on concrete proposals for how we might funnel high school students into HEAL careers.

One promising approach in this regard would be to expand funding for “Academy of Health Careers” charter high schools and magnet programs, which put students on the pathway to health care professions and allow them to obtain some professional credentials (e.g., as nursing assistants, paramedics, or medical administrative assistants) even before graduation. As it happens, there was an Academy of Health Careers program at my high school, and a close friend credits his time in it with his eventual decision to go into nursing. These programs are few and far between, however; we should study whether expanding them could reduce the health care labor shortage or increase men’s share in nursing and lower-skilled health care jobs.

Reeves’s final chapter takes on the cultural and psychological void left for men by the marginalization of marriage. If women’s mass entrance into the paid workforce has allowed them to flourish without husbands (as we’ll see, this is a big “if”), then our current challenge, he thinks, is to enable men—and especially fathers—to flourish without wives. In particular, Reeves would like us to reimagine fatherhood as a direct relationship to kids, not mediated by moms. To facilitate that new norm, he proposes a national paternity leave policy (which dads could use any time until their kids are 18), and a legal regime less punitive toward and suspicious of single fathers.38

Could “direct fatherhood” realistically substitute for marriage in the lives of many men?39 I doubt it. For one thing, marriage is unique among human institutions in the way it socializes and dignifies core aspects of male motivation. Young, unmarried men’s elevated sex drives, risk propensity, and aggression make them the most dangerous demographic in every society.40 Marriage (again, especially monogamous marriage) works not to squash, but to sublimate those appetites, helping men to convert mere lust into lifelong love; mere aggression into protectiveness; and heedless gambling into calculated, productive risk-taking.

Direct fatherhood, which typically means living apart from one’s children and without any committed relationship to their mother, cannot bring these positive incentives to bear on men in the way marriage does: it cannot channel and socialize men’s naturally elevated libidos, and offers them less scope for playing the role of provider and protector, which marriage at least notionally affords. As such, we should expect direct fatherhood, even in a society which more explicitly recognized and valorized it than ours does, to have more modest effects in promoting men’s flourishing than marriage does today.

Not Trad Enough

In Reeves’s view, however, hoping to restore marriage to its former cultural centrality is utopian (a charge he good-naturedly leveled at me during a dinner conversation some months ago), and what’s more, immoral, since “economically independent women can now flourish whether they are wives or not.”41 A renewed marriage norm would necessarily require “making women dependent again in order to resupply men with purpose.”42 Reeves’s worry seems to be that, within a newly marriage-centric culture, husbands would resume their traditional role as sole breadwinners, with wives acting as dedicated homemakers and caregivers.

But this vision of marriage becomes less plausible the further back one looks from, say, 1950s America. After all, there were spinsters, nuns, and beguines long before the sexual revolution, many of whom commended the celibate life at least in part for the independence it afforded. According to her hagiographer, Juetta of Huy, a thirteenth-century beguine, “wisely intuited” while still a girl “that the married state was a heavy yoke, as were the awful burdens of the womb, the dangers of childbirth, the education of children; and on top of all this, the fate of husbands was so unsure. . . . So she rejected all husbands, imploring her father and mother by all means that they would leave her without a man.”43

Moreover, for most of our species’ history, women have been significant players in the economic lives of their households as well. As Dorothy Sayers observed in 1938, the first sexual revolution was arguably the Industrial Revolution, in which men took over whole industries which had formerly been the special province of women, including

the whole of the spinning industry, the whole of the dyeing industry, the whole of the weaving industry. The whole catering industry and . . . the whole of the nation’s brewing and distilling. All the preserving, pickling, and bottling industry. And . . . a very large share in the management of landed estates. Here are the women’s jobs—and what has become of them? They are all being handled by men. . . . Modern civilization has taken all these pleasant and profitable activities out of the home, where the women looked after them, and handed them over the big industry, to be directed and organized by men.44

Or, as Erika Bachiochi put the same point recently, “Men and women made distinctive—gendered—contributions in the family, but before industrialization nearly all work might be considered ‘domestic work,’ part and parcel of the sustenance and management of the interdependent and productive household.”45

Women’s mass entrance into wage labor, though as revolutionary in its day as men’s entrance into it had been in the century prior, can equally be viewed as reviving, under very different conditions, the premodern norm of women’s engaging in productive work alongside men, albeit with somewhat different specialties, and with their time more evenly divided than men’s between work and childcare. In some ways, this arrangement is more traditional than the postwar ideal of the leisured housewife, though with the distinctly modern limitation of alienating men’s and women’s work alike from home and children.46 As Mary Harrington has insisted, “tradwives aren’t trad enough.”47

Reeves treats the persistence of “the husband breadwinner norm” as an irrational survival from a world in which it served a now lost economic purpose. Even today, however, among married women with children at home, 56 percent still prefer not to work full-time.48 And as Reeves himself notes, only half of women who earn graduate degrees at Harvard—the women with “the widest choices and the greatest economic power”—are working fifteen years after graduation.49 These preferences, both expressed and revealed, for the “husband breadwinner norm,” aren’t in tension with the typical modern mother’s economic aspirations, but rather reflect the desire to balance the goods of economic achievement and investment in children.

And of course, children are the core issue. Marriage is a human (near) universal, not to ensure women’s economic dependence, but because, when men and women have sex, children frequently result, and men can more easily ignore the consequences of sexual liaisons than can women. Marriage (and again, especially monogamous marriage) is above all a way of forcing a man to assume responsibility for his children in exchange for—in Joseph Henrich’s helpful if somewhat crass summary—“preferred sexual access and stronger guarantees that [his mate’s] kids are in fact his kids.”50 The genius of the institution is the way it at least partly harmonizes the needs and desires of men, women, and children alike.

The twentieth-century transformation in sexual mores was not driven simply by women’s entrance into the labor market, but also by a radical technological development, which exercises a pervasive but unspoken presence in Of Boys and Men: the pill. As Louise Perry writes in her recent book, The Case against the Sexual Revolution, “At the end of the 1960s, an entirely new creature arrived in the world: the apparently fertile young woman whose fertility had in fact been put on hold.”51 If monogamous marriage required men to have sex (more) like women, the pill and its successors have allowed women to attempt to masculinize their sex lives, to approach sex as an act with neither a past nor a future, free of attachments or intimacy.

Reeves rightly stresses the importance of marriage in promoting men’s flourishing, but he is too sanguine about the effects of a post-conjugal society on women and children. The sexual revolution, after all, has seen a stunning rise in the rate of births to unmarried American parents (from 5 percent in 1960 to 40 percent today), despite the fact that 87 percent of women still say they would prefer to be married before having children.52 This sea-change is the result of sharp increases in extramarital sex and the fact that, as Perry notes, as typically used, even the pill is only about 91 percent effective in preventing pregnancy.53 It also owes much, as Reeves points out, to the collapse in the cultural norm that unwed parents should swiftly marry, if need be at the point of the infamous shotgun.54

And at least with respect to the welfare of children, there is strong evidence that marriage offers better outcomes than any foreseeable configuration of “direct fatherhood.” Reeves himself stresses both that fathers play a distinctive role in the nurture and education of children at many stages in their development, and that “within 6 years of their parents separating, one in three children never see their father, and a similar proportion see him once a month or less.”55 Moreover, children growing up in single-parent households are about five times more likely to live in poverty than those in married households.56 By age twenty-eight, 24 percent of black men and 18 percent of white men who grew up in a single-parent home have been incarcerated, compared to 14 percent and 8 percent, respectively, of those who grew up in a house with both biological parents.57 We thus have ample reason to want norms which encourage mothers and fathers to live together while they raise their children, and institutions to render that arrangement durable and socially valued.

Optimism about modern sexual emancipation is an axiom for most feminists, and it is evident as well in Reeves’s passing defenses of prostitution or online pornography.58 As Perry shows in graphic detail, however, the world of masculinized sex systematically disadvantages and frequently brutalizes women. Prostitution and pornography are not only bound up with human trafficking and the exploitation of the poor and mentally ill,59 but even in the best cases, intrinsically foster a dehumanizing attitude toward sex—as a relation to an object of pleasure rather than as communion with another subject—and a demeaning view of women in the men (almost always men) who patronize them.60

Moreover, the culture of casual sex has an alarming degree of continuity with these more obviously troubling corners of the sexual revolution. Many men might enjoy—at least for a season—a culture in which sex is the normal outcome of a first date. But then, men will typically be the larger and stronger party in any sexual encounter, as well as the one with higher “sociosexuality”—the appetite for sexual novelty and diversity.61 For women, however, casual sex typically means at least discounting their own preferences for “a hand held in daylight,” as a disenchanted co-ed poignantly put it to Perry.62 At worst, it means courting the risk of unplanned pregnancy or even violence—in one recent “campus-representative study of undergraduate and graduate students,” a third of female respondents reported having been choked during their most recent sexual encounter.63

Reeves surely wouldn’t condone any of the depravities canvassed just above. I suspect, instead, that he would view them as evils which are in principle separable from the larger project of sexual liberation. In my view, however, they are the logical and inevitable outcome of that project’s reduction of sexual morality to the thin and ambiguous principles of consent and non-malevolence. The early feminists knew better—as Bachiochi notes, “[Mary] Wollstonecraft and the early suffragists argued,” not for sexual license for women, but “for sexual integrity for both sexes. ‘Votes for women, chastity for men’ was actually a suffragist slogan.”64

Given this ill-fit between women’s needs and desires and our increasingly deregulated sexual culture, it is small surprise that many empirical studies of marriage show that it strongly promotes women’s well-being as well. Our team at the Human Flourishing Program has recently published perhaps the most rigorous such study to date, in a paper lead-authored by my colleague Ying Chen, on the effects of the decision to marry on about twelve thousand female nurses.65 After about twenty-four years of follow-up, we found that, even after controlling for race, income, age, and a range of important health behaviors, marriage was associated with greater life satisfaction, greater mental and physical health, and even a 35 percent reduction in all-cause mortality.

Work-Friendly Families or Family-Friendly Work?

These data do not suggest that women’s economic independence fully compensates for the loss of marriage. On the contrary, marriage remains a critical pathway to flourishing for women as well as men, which is precisely what you would expect if, as I suggested above, marriage has the hallmarks of an institution designed to better align human sexual life with women’s typical needs and desires as well as with men’s long-term good. Perry puts the point well, observing that “practically-minded feminists . . . need a technology that discourages short-termism in male sexual behavior, protects the economic interests of mothers, and creates a stable environment for the raising of children. And we do already have such a technology, even if it is old, clunky, and prone to periodic failure. It’s called monogamous marriage.”66

Reeves worries that efforts to revive marriage as a normative institution would threaten women’s gains in education and in the professions. But realist feminists such as Bachiochi, Harrington, and Perry, among others, are now making a strong case that women’s flourishing still requires monogamous marriage as a cultural norm. Not that we should seek to recreate the preindustrial world of economically vital but politically disenfranchised women, nor even the postwar ideal of the politically enfranchised but economically dependent housewife (though neither should we sneer at women, or indeed men, who want to raise their children full-time rather than work for pay).

Rather, our goal should be to make it easier for men and women to build and sustain families. We could start by making work less of a threat to that end. As Reeves rightly laments, “The goal of public policy often seems to be to create work-friendly families, rather than family-friendly work.”67 The post-Covid shift to partly virtual work is a promising development for the laptop class. We could significantly help service workers, as well, by banning just-in-time scheduling, which is a particular nightmare for wage-earning parents.68 More broadly, we could invest in regular, means-tested cash transfers to parents, to assist them in the essential work of nurturing our society’s next generation.69 And we could better fund the federal Healthy Marriages and Responsible Fatherhood program, which supports pro-marriage and pro-fatherhood policies and interventions, many of them quite effective.70 At present, it receives an annual $150 million appropriation, which is a pittance compared to the $102 billion annual budget of the Department of Education.

Longer term, restoring marriage as a cultural norm will likely demand a sexual counterrevolution to overthrow the regime of “cheap sex,” which has made it easy to treat marriage as merely a boutique lifestyle, rather than the load-bearing institution it in fact remains for most people.71 The notion that all sexual behaviors or family structures are of equal social value is a paradigm of what Rob Henderson has termed “luxury beliefs,” namely “ideas and opinions that confer status on the upper class, while often inflicting costs on the lower classes.”72 Cultural and economic elites are disproportionately likely to enjoy stable marriages, even as they foster a culture of sexual license whose evils are borne principally by poor and less-educated men, women, and children. Perhaps above all, we need married producers, professors, and pundits who are willing to, in Charles Murray’s words, “preach what they practice.”73

In that light, Reeves’s charge of utopianism might ring true after all: these are not changes that will come soon, or easily. Nonetheless, if we are to find our way again, we will have much to learn from Of Boys and Men. Reeves has given us a sober, compassionate, and insightful guide to the challenges facing today’s weaker sex, and a rich resource for how we might begin to help boys and men truly flourish. Many of his proposals deserve immediate consideration by legislators at the federal, state, and local levels, and I suspect that, in the decades to come, we will owe him much for important changes in how boys are educated and men employed.

Reeves goes wrong principally in thinking that his commitments to women’s political and economic agency require marginalizing marriage. Happily, correcting this mistake would allow him to fully embrace his core intuition that there cannot be any true opposition between what is good for men and for women: both are suffering amid the decline of marriage, and neither are likely to flourish unless its centrality is recovered.

This article originally appeared in American Affairs Volume VII, Number 2 (Summer 2023): 115–26.

Notes

Thanks to Erika Bachiochi and Flynn Cratty for their thoughtful comments on an earlier draft of this essay.

1 Richard Reeves, Dream Hoarders (Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2018), 3.

2 Richard Reeves, Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male is Struggling, Why it Matters, and What to Do About It (Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2022).

3 Hanna Rosin, The End of Men: And the Rise of Women (New York: Riverhead Books, 2012). The quotation above is from Rosin’s essay of the same title in the Atlantic. Hanna Rosin, “The End of Men,” Atlantic (July/August 2010).

4 Kay Hymowitz, Manning Up: How the Rise of Women Has Turned Men into Boys (New York: Basic Books, 2011).

5 Nicholas Eberstadt, Men Without Work (Pennsylvania:Templeton Press, 2016).

6 Christina Hoff Sommers, The War against Boys: How Misguided Policies Are Harming Our Young Men (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014 [2001]).

7 “Tomorrow’s Second Sex,” Economist, 340 (1996): 25-30, quoted in Sommers, The War against Boys, 152.

8 George Gilder, Sexual Suicide, (New York: Quadrangle, 1973).

9 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 18–19.

10 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 19–20, 25–30.

11 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 28.

12 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 21–24.

13 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 37.

14 Immigration rates garner two brief references in Reeves, Dream Hoarders, 4, 27. On this issue, see in particular Michael Lind’s The New Class War: Saving Democracy from the Managerial Elite (New York: Penguin, 2020), 12–14, 22–26.

15 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 34.

16 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 44–45.

17 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 184.

18. Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 185.

19 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 79.

20 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 52.

21 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 59.

22 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 123; The expression “testosterone suppression system” is Joseph Henrich’s. Joseph Heinrich, The WEIRDest People in the World (New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 2020), 268.

23 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 51.

24 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 83.

25 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 100–3.

26 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 145.

27 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 140.

28 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 112.

29 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 159.

30 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 156.

31 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 126-29; Rong Su and James Rounds, “All STEM Fields Are Not Created Equal: People and Things Interests Explain Gender Disparities Across STEM Fields,” Frontiers In Psychology 6, no. 25 (February,2015).

32 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 165–66.

33 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 172–73.

34 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 178–79.

35 Along with Oren Cass’s team at American Compass, American Affairs is a particularly rich source for detailed proposals and general good sense on trade and industrial policy. See, for example, Steve Keen, “Ricardo’s Vice and the Virtues of Industrial Diversity,” American Affairs 1, no.3 (Fall 2017); Kevin Gallagher and Sandra Polaski, “Reforming U.S. Trade Policy for Shared Prosperity,” American Affairs 4, no.2 (Fall 2020).

36 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 196.

37 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 193.

38 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 218.

39 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 211–13.

40 Henrich, The WEIRDest People in the World, 279–80. Henrich exploits the natural experiment offered by China’s “one child” policy to demonstrate the link between the pool of unmarried young men and crime rates.

41 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 60.

42 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 159.

43 Quoted in Walter Simons, Cities of Ladies: Beguine Communities in the Medieval Low Countries, 1200–1565 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 69.

44 Dorothy L. Sayer, “Are Women Human?,” Logos 8, no.4 (Fall 2005): 168–69.

45 Erika Bachiochi,“Sex-Realist Feminism,” First Things, April 2023.

46 On this theme, see also Erika Bachiochi, “Pursuing the Reunification of Home and Work,” American Compass, July 15, 2022.

47 Mary Harrington,“Why Tradwife Isn’t Trad Enough,” January 30, 2020.

48 Robert VerBruggen and Wendy Wang, “Dad’s Income and Mom’s Work,” Institute for Family Studies, January 23, 2019.

49 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 46.

50 Henrich, The WEIRDest People in the World, 72.

51 Louise Perry, The Case Against the Sexual Revolution (Cambridge, U.K.: Polity), 6-7.

52 Lyman Stone, “Putting Things in Order: Relationship Sequencing Preferences of American Women,” Institute for Family Studies, March 9, 2023.

53 Perry, The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, 166.

54 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 55.

55 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 61.

56 “Families with Related Children That Are below Poverty by Family Type in the United States,” Annie E. Casey Foundation, accessed April 21, 2023.

57 Brad Wilcox, “Less Poverty, Less Prison, More College: What Two Parents Mean for Black and White Children,” Institute for Family Studies, June 17, 2021.

58 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 121.

59 Perry, The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, 94–113, 135–49.

60 Perry, The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, 112–13, 152–53.

61 Perry, The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, 73–75.

62 Perry, The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, 82.

63 Debby Herbenick et al., “Frequency, Method, Intensity, and Health Sequelae of Sexual Choking Among U.S. Undergraduate and Graduate Students,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 51, (2022): 3121–39. Thanks to Brad Wilcox for pointing me to this important research.

64 Erika Bachiochi, The Rights of Women: Reclaiming a Lost Vision (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2021), 37.

65 Ying Chen et al., “Marital Transitions During Earlier Adulthood and Subsequent Health and Well-Being in Mid-to-Late-Life Among Female Nurses: An Outcome-Wide Analysis,” Global Epidemiology 5, (2023).

66 Perry, The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, 181.

67 Reeves, Of Boys and Men, 217.

68 Bachiochi, Pursuing the Reunification of Home and Work.

69 Oren Cass and Wells King, “The Family Income Supplemental Credit,” American Compass, February 18, 2021.

70 Alan J. Hawkins, “Are Federally Supported Relationship Education Programs for Lower-Income Individuals and Couples Working?” American Enterprise Institute, September 2019.

71 On “cheap sex,” see Mark Regnerus, Cheap Sex: The Transformation of Men, Marriage, and Monogamy (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2017).

72 Rob Henderson, “Luxury Beliefs Are Status Symbols,” Rob Henderson’s Newsletter (blog), July 12, 2022.

73 Charles Murray, Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010 (New York: Crown, 2012), 299.