“A sword by itself rules nothing. It only comes alive in skilled hands.”

—Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

Film credits are generally a boring affair, and most audiences will have stopped paying attention once the reel rolls around to the gaffer, foley, and drivers for the production. For those patient enough to sit through the credits of Disney’s live-action remake of Mulan (released in September 2020), however, there lurked a provocative acknowledgement of some unusual partners, namely eight government agencies from China’s Xinjiang province, home to at least twelve million Uighurs. These agencies included the Publicity Department of Xinjiang and the Turpan Municipal Bureau of Public Security, the latter of which was sanctioned in October 2019 for human rights abuses. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and former secretary Mike Pompeo both have explicitly called the Chinese government’s treatment of the Uighurs “genocide,”1 one of the few points on which the Biden and Trump administrations readily agree.

Disney’s president of film production, Sean Bailey, defended the studio’s Xinjiang partnerships in writing to British politicians, boasting of the film’s “inclusivity” and shifting responsibility for controversial decisions to its local partner, the aptly named Beijing Shadow Times Culture Company.2 Even staunch Hollywood ally Variety was evidently unconvinced by Disney’s claim of innocence, noting that, at the time of preproduction and filming, “the campaign against Uighurs would have been nearly impossible to ignore . . . if only because of the extreme surveillance that travelers there would have been subject to wherever they went, and the visibly growing systems of checkpoints and security checks.”3

Compare this episode with Disney’s activist stance on U.S. political issues. In 2016, Disney threatened to stop all production in Georgia, in the middle of active filming for its latest blockbuster Guardians of the Galaxy outside Atlanta, if Georgia passed religious liberty legislation that would have lessened protections for LGBT individuals within the state.4 The campaign was successful, and the governor of Georgia vetoed the bill. Disney was the first major movie studio to take this stance, and the company justified its decision on ethical grounds: “Disney and Marvel are inclusive companies, and although we have had great experiences filming in Georgia, we will plan to take our business elsewhere should any legislation allowing discriminatory practices be signed into state law.”5

One word in particular stands out in both of Disney’s official statements: “inclusive.” Disney appealed to the same value in justifying its decisions in both China and the United States, but with opposite responses to the respective controversies. In the era of ubiquitous forced corporate apologies, the Mulan statement is most noteworthy for what it avoided: any acknowledgement of an ethical violation, or of the severity of what was transpiring in Xinjiang. Disney affirmed its ethical posture and “inclusivity” with Mulan, while conspicuously avoiding language that might offend Chinese authorities. In the case of Georgia, however, the company threatened to boycott the state because of proposed legislation and made clear that ethical considerations would be paramount in its selection of filming locations.

The significance of popular entertainment fare featuring imaginary superheroes and fanciful storylines may seem trifling when compared to real-world issues of cybersecurity, public health, and military intrigues between China and the United States. So it is perhaps unsurprising if American policymakers have neglected matters of the entertainment trade and the cultural tug-of-war relative to other problems. Yet given the considerable impact Hollywood has had on a number of cultural issues across generations, policymakers perhaps should be more attuned to the “soft” but undeniable power of this cultural apparatus here and abroad.

Follow the Money

America’s role in the international media and entertainment industry is commanding. A recent government study estimates that U.S. entertainment companies account for $717 billion in annual revenue, approximately a third of the global industry.6 While the country comprises only 4 percent of the world’s population,7 it is by far the world’s largest contributor to the cultural economy. Some of this imbalance arises from stronger protections for artistic IP in highly developed nations. But the more significant force at play is evident to anyone who has traveled to any foreign country: American movies, music, and cultural output are widely in demand across nearly all societies. In spite of continuing piracy in many countries, the United States maintains a trade surplus in filmed entertainment. In 2016, this figure stood at $10.3 billion, approximately 4 percent of the whole U.S. private sector trade surplus across all industries.8

China has only recently become the centerpiece of the film export market and global box office ambitions. While the Chinese cinema industry was once characterized by minuscule ticket prices and a tightly limited number of offerings, the past two decades have seen stratospheric growth in box office revenues. In 2003, the cumulative revenue across the seven cinematic releases in China was just north of $6 million. In 2019, that same figure was over $9 billion from 455 films.9

These growth rates are striking in comparison to U.S. domestic box office tallies, which have stagnated around $11 billion in the past few years. The U.S. market saw robust growth throughout the 1980s and ’90s (from $918 million in 1981 all the way up to $7.4 billion in 1999) but began to decelerate, and even decline in some years, starting in 2003.10 Larger and more advanced home televisions, as well as the higher quality of shows available at home, are seen as the chief causes of this dynamic. Nevertheless, an ineluctable fact confronts any business-minded person in Los Angeles: China is home to rip-roaring growth, while the United States is stagnating.

Although Chinese-language films seldom see box office riches in U.S. cinemas, the reverse has occurred frequently. Non-Chinese films comprised between 36 and 53 percent of total box office revenues in China from 2011 to 2019.11 Transformers, The Fast and the Furious, and Avengers movies have been particularly popular in China. Hollywood’s bread and butter of explosive action sequences, flashy special effects, and high-octane storylines remain crowd-pleasers in this foreign market, as in many others, as Tinseltown has continued to refine the formula that, in many regards, it invented. Like it or loathe it, Hollywood has been one of the principal emissaries of American culture to the world in the past century.

China’s Quest for Market Share at Home and Abroad

Nonetheless, China has been keen to supplant its adversary, particularly in its domestic market. As cinemas in most of the world shuttered in the wake of the pandemic in 2020, China was able to keep its own venues relatively open, and accordingly notched one of the top-grossing movies worldwide: The Eight Hundred12 generated over $400 million in ticket sales. Unapologetically nationalist themes and CCP-vetted dialogue, however, mean that productions successful among Chinese audiences can rarely swim outside Chinese waters, commercially or critically.

Time will tell whether China will be able to change this and replicate Hollywood’s international vitality. While Ang Lee’s 2000 epic Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Zhang Yimou’s 2002 Hero showed that Chinese-language films can have crossover success with Western audiences, that momentum appears to have long since stalled.

Ang Lee’s status as an avatar of Chinese filmmaking is also questionable, in part because he actually hails from Taiwan and developed as a director mainly in the United States, where he now resides. His first three films were directed in Taiwan, before he made his American debut in 1995 with Sense and Sensibility.13 Perhaps the most enduring film of his career to date is the most American of all, and one that never could have been created under Chinese censorship: Brokeback Mountain. Indeed, Brokeback was not screened in China.14 China claimed proud ownership of Crouching Tiger, but Lee’s more subversive material has been shielded from view.

Nor is Ang Lee’s story a unique one among Chinese filmmakers who have succeeded internationally. The two towering artists who exemplify this category are Edward Yang and Wong Kar-Wai. The former is Taiwanese, and the latter is principally associated with Hong Kong. In other words, China’s most internationally illustrious moviemakers come from disputed territories. Both, as well, maintain a subversive strain in their filmmaking. Of the subset of Wong’s films that were allowed to be released in mainland China, one of them was, surprisingly, 2046, whose title is a reference to the Chinese promise not to alter Hong Kong’s distinctive local governance for fifty years after the British handover in 1997.15 After having some of the steamier sexuality edited out,16 this movie was released in 2004—long before the current troubles with Hong Kong.

Therein lies the tension in China’s quest for cultural dominance: attempts to co-opt parts of the supply chain are sometimes supported, but other times the vessels of self-expression veer too far into themes that challenge an authoritarian regime. No movie from the PRC has ever won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, the most competitive film festival in the world and perhaps the chief marker of highbrow critical sentiment. Even the limited entries accepted to be screened at the festival in recent years seem increasingly likely to run afoul of China’s censorship boards, with The Wild Goose Lake and Ash Is Purest White both featuring somewhat sympathetic portrayals of protagonists from the criminal underworld.

Off-Camera Maneuvers

With international critical and even commercial strength both remaining well out of reach, China has in recent years resorted to further behind-the-scenes maneuvers, attempting to influence the U.S. filmmaking industry through the power of the purse. In the 1990s, this was effectively impossible for the regime, as the small Chinese market was an afterthought for Hollywood businesspeople. Sony Pictures released its film Seven Years in Tibet in 1997, sparing nothing in its explicit attack on the situation in the region: “One million Tibetans have died as a result of the Chinese occupation of Tibet. Six thousand monasteries were destroyed.” In a feeble retort, China temporarily banned actor Brad Pitt and the film’s director from the country, yet the film went on to gross an impressive $131 million globally. As the Chinese market expanded, however, and as Chinese investment into Hollywood skyrocketed, studios became less eager to make such movies. By 2016, Chinese investment across the U.S. entertainment industry was estimated at $4.78 billion.17

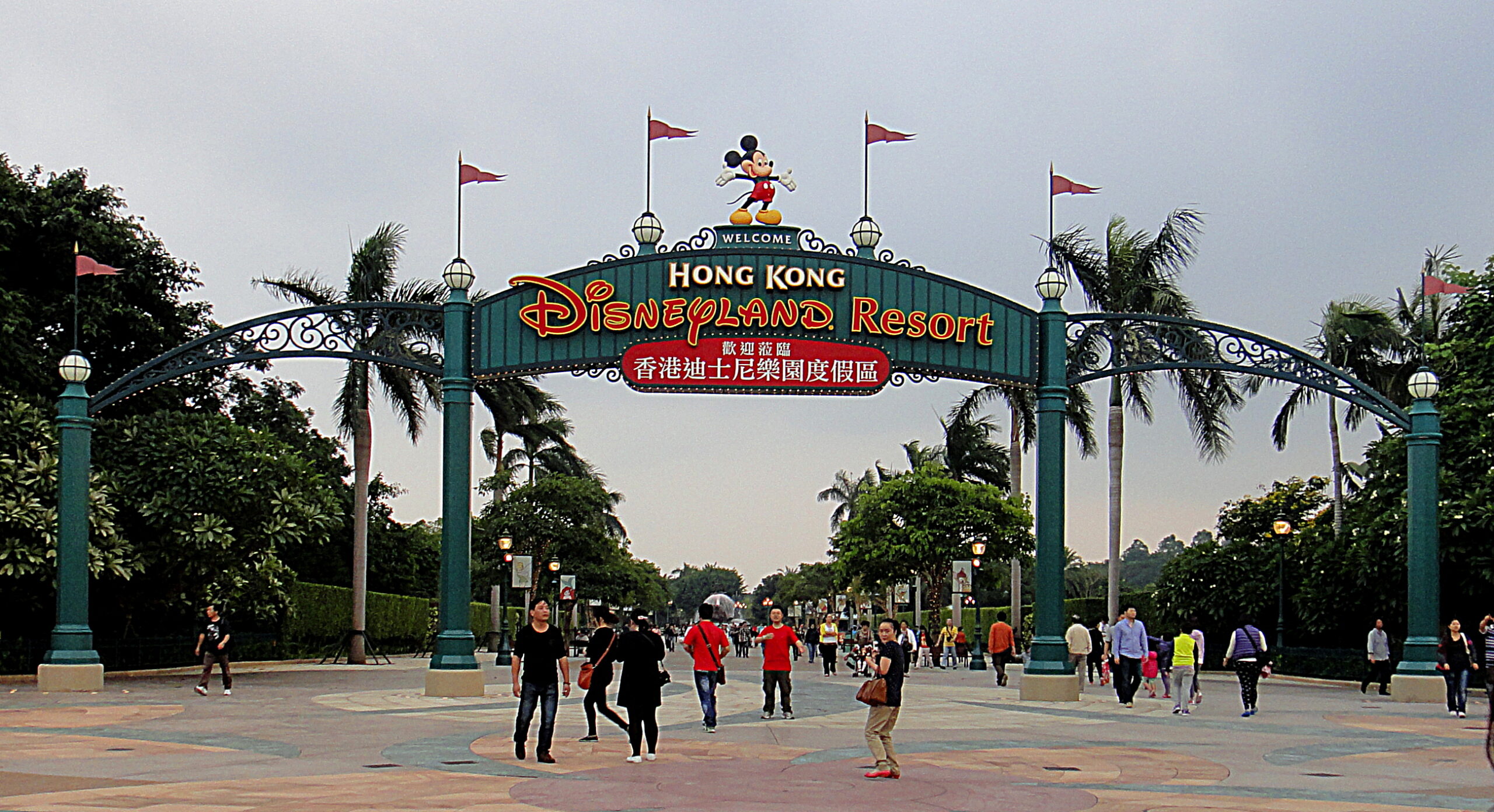

At no studio is this transformation more evident than Disney. The Mouse House had its own Tibet-themed flap with China in 1997, in the form of Martin Scorsese’s Kundun. Unlike Seven Years in Tibet, Kundun flopped, and Disney soon began to mend ties with China after receiving official threats of an embargo on their wares. Disney’s CEO at the time, Michael Eisner, hired Henry Kissinger for damage control and called the movie a “stupid mistake” to Zhu Rongji (then the premier of China), attempting to minimize the whole affair by noting that “other than journalists, very few people in the world ever saw it.”18 In the ensuing years, Disney gradually worked toward an agreement for Shanghai Disneyland, and subsequent CEO Bob Iger generated considerable revenue out of the China relationship, making the country a central component of Disney’s growth strategy.

The charm offensive has been so unrelenting that Iger recently sought to become the new U.S. ambassador to China.19 His demonstrated obsequiousness toward the Chinese government appears to have been a bridge too far for the Biden administration, but there is little doubt that Iger will continue to be a major unofficial power broker between the two nations as executive chairman of Disney. As the Chinese government takes a 57 percent share of Shanghai Disneyland revenue (particularly money from hotels, restaurants, and physical products sold on the grounds), Iger may still be able to act as an emissary from one nation to the other, but in the opposite direction from his original aspiration.

Disney’s willingness to intervene for China was on display again in 2020, when Chinese-born filmmaker Chloé Zhao’s film Nomadland quickly became an Oscar frontrunner. Zhao was discovered to have gone rogue in an obscure interview from years ago, pointing out that there were “lies everywhere” in her native country. Since Nomadland would be running on Hulu, a Disney-owned streaming service, and since it was produced by Fox Searchlight, also a Disney subsidiary, the company could not distance itself from the project. Instead, a representative from Fox Searchlight pressured Filmmaker magazine to remove the quotation. It was too late, however, and Disney’s behind-the‑scenes machinations were already in public view. Zhao could critique the social situation in America at feature length, but even a passing external reference critical of China led to the film being banned there.20

The Bamboo Curtain

There is some dramatic irony in Hollywood’s sycophantic relationship with China. After all, this is the country that has historically had some of the highest movie piracy rates in the world (estimated as high as 90 percent in one study by LEK Consulting21). There are some signs that the Chinese government may be trying to clamp down on piracy—perhaps returning a favor to its allies in L.A. In February of 2021, law enforcement officers in Shanghai arrested fourteen individuals who had worked for Renren Yingshi, one of the most popular piracy-reliant streaming services in China.22 The arrests had a chilling effect on other services, some of which read the writing on the wall and disappeared from view. Renren Yingshi and others had been the gateway for many Chinese to access Western shows with decent Mandarin subtitles.

Nevertheless, China has rigged its digital supply chain in such a way that Chinese companies will ultimately control the market outside of cinemas. Foreign ownership of or investment stakes in streaming platforms is forbidden.23 For Netflix, China is one of only four territories in the world where the streaming service remains unavailable. The other three are North Korea, Syria, and Crimea.24 Disney’s streaming service, Disney+, has seen great commercial success internationally, and after all the political maneuvering by Iger and other executives, there seems to be some possibility that the studio could make headway into the currently blockaded Chinese digital market, perhaps through a partnership with a local entity. For the time being, though, the reality remains that U.S. studios are able to reap little benefit on the digital front, other than through sales of individual, carefully censored pieces of content. Netflix sold some of its original shows to the Chinese service iQiyi in 2017, but reportedly for a small price, and also with the stipulation that iQiyi would have control over all the data on consumer viewing.25

Even the situation in Chinese cinemas is flashing warning signs for Hollywood studios. The U.S. market share there shrank to a paltry 11 percent in 2020, and 2021 appears to have delivered similar results.26 Even before the pandemic changed release plans for Hollywood, this market share was down to only 29 percent in 2019.27 Chinese audiences have been showing an increasingly nationalistic streak in their viewing patterns, and as Chinese studios have built up formidable infrastructure to produce these sorts of films themselves, it seems unlikely that American companies will regain their peak market share in China.

Furthermore, Xi Jinping’s CCP applies an ever-heavier hand to all sectors of society. The government is becoming more explicit in its oversight and ultimately suppression of creative industries, with the National Radio and Television Administration announcing a far-reaching crackdown within China, including against any depictions involving “niang pao,” a slur against effeminate men that literally translates as “girlie guns.”28 The announcement also criticizes the “overly entertaining trend” in the industry and tells entertainment professionals that they must “insist on correct political direction and values.”

With Chinese authorities exerting such strict discipline against China’s own creators, there is even less opportunity for Americans to create entertainment that would be simultaneously appealing across the globe and satisfying to these Communist censors. How would an entertainment studio know how to avoid being “overly entertaining,” after all? And so, in an ironic plot twist, Hollywood may find itself in the perverse position of being written out of a script in which it presumed to have the leading role.

Securing the Film “Supply Chain”

With China’s box office of roughly $7 billion in 202129—the largest in the world for the second year running—some Hollywood honchos still seem keen to chase after the sliver that may remain for them. Yet there are signs in Congress and even in Hollywood that key figures are willing to stand up to China. Only time will tell whether this translates into robust legislation or a meaningful business shift for the industry.

Senator Jeff Merkley has introduced bipartisan legislation (along with Senators Warren, Rubio, and Cornyn) to combat China’s censorship campaign against American companies, with an eye toward the film industry.30 Filmmakers Judd Apatow and Quentin Tarantino, among the top tier of American directors, publicly criticized China for its bullying tactics, and the latter lost Chinese distribution for his film Once Upon a Time . . . In Hollywood.31 Sony Pictures film head Tom Rothman stood by Tarantino “100 percent,” even with Chinese coproducers on the film. Rothman revealingly remarked, “Obviously that had financial consequences, but character is tested when things are difficult, and not when they’re easy.”32 Other U.S. studios may not be making films about Tibet or the Uighurs now, but occasionally there are signs that some of them are less willing to take all cues from a foreign government—and are likely increasingly resentful of the fact that China has not delivered on the bountiful profits that seemed assured a few years ago.

On the other hand, some studios remain fully in Chinese hands, such as Legendary Entertainment (home to Pacific Rim, Jurassic World, Godzilla, and Dune), which was acquired by Dalian Wanda for $3.5 billion in 2016.33 Chinese government authorities, however, were reportedly displeased with this large acquisition of an American entertainment company (perhaps not wanting to give too much support to American businesses), and it is no coincidence that Chinese investment radically slowed after 2016.34

This raises a crucial question: if there are unwelcome consequences for American studios who disobey Chinese marching orders, what serious consequences are there in the United States for companies who do obey the will of a hostile foreign government? Recent history suggests that the only consequence is mild to moderate opprobrium among certain pundits, which is evidently not enough to stop the top American studio from filming in Xinjiang with the help of the security agency responsible for genocide.

Senator Merkley’s aforementioned bill could be a significant step toward creating more visible consequences for abuses in the digital supply chain. Further action may be necessary, however, to address cases such as Mulan. The United States has issued a number of “withhold release orders” (WROs) recently for physical products coming from Xinjiang, especially cotton, because of evidence of forced Uighur labor being used in their production. There is not an effective pathway, however, to withhold a digital release such as Mulan. Although Customs and Border Protection could conceivably have issued WROs on the DVDs of Mulan, the effects would have been minor, as the vast majority of people who watched the film did so via streaming.

Bringing visibility to the full digital supply chain is a worthy starting point, and requiring conspicuous notices at the beginning of a film where foreign government abuse has been found has been suggested as a means to impose far more accountability.35 While a parallel pathway ought to exist for full-blown digital WROs to be issued when forced labor is involved, there is not sufficient evidence that forced Uighur labor was used in the filming of Mulan.

Congress also has other points of leverage over the digital supply chain, particularly in the burgeoning area of digital taxes and tariffs. The Biden administration has even shown a willingness to impose (or at least threaten) tariffs in response to other countries’ taxes on digital services, proposing 25 percent tariffs on $2.1 billion of products from Austria, Britain, India, Italy, Spain, and Turkey.36 A tariff could be applied to film and television productions with any filming in China. An extensive international tax system is already in place to incentivize filming in certain countries, including tax credits of 20 to 30 percent for productions filmed in countries such as France and Hungary.37 Sizable disincentives for working in China or with Chinese studios could swing Hollywood further from any reliance on the country. Tariffs can also be levied, or threats of such tariffs can be communicated, on goods, digital or physical, from countries that fail to protect American intellectual property, until better enforcement is demonstrated in these countries. This could provide additional muscle to artistic industries in which the U.S. enjoys a trade surplus but whose companies have suffered from widespread international piracy.

President Biden is especially familiar with the situation for American filmmakers in China because he was a key figure behind the 2012 U.S.-China Film Agreement. The United States filed a World Trade Organization (WTO) complaint in 2007 over China’s restrictions, and the United States won. Even on appeal in 2011, China lost again.38 The 2012 agreement was supposed to, in then vice president Biden’s words, “make it easier than ever before for U.S. studios and independent filmmakers to reach the fast-growing Chinese market.”39 A decade later, it is evident that China has gone in the opposite direction, further restricting U.S. releases and disregarding its WTO obligations. Accordingly, it is now in President Biden’s hands to push the matter further and to escalate the broader trade negotiations with a delinquent partner.

Intellectual property protection is also one of the rare policy areas that have elicited continued bipartisan support. While some right-leaning libertarians oppose protections as disruptions of a pure free market, and while some left-leaning activists oppose the capitalist underpinnings of a cultural economy, many policymakers of both parties seek to bolster a market that punches far below its true economic weight. The Protecting Lawful Streaming Act of 2020 was a positive step in this direction, escalating the penalties for pirate sites from misdemeanor to felony charges.40 Senator Thom Tillis, ranking member of the Subcommittee on Intellectual Property within the Senate Judiciary Committee, has been particularly prominent in pushing stronger IP protections, including in proposed revisions to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998.41 Extending protections meaningfully beyond U.S. borders will also require creative collaboration with trade authorities, such as Senate Finance’s Subcommittee on International Trade, Customs, and Global Competitiveness.

In parallel, as Disney is the most eager collaborator with the Chinese government, policymakers can target Disney’s significant physical goods imports from China. Disney has already drawn attention for exploitative working conditions at some of the factories it uses in China, and so tariffs can be applied to toys and products manufactured there.42

Indeed, the American electorate appears to have an increased willingness to address supply chain reliance on China, especially after U.S. dependence on Chinese medicine and medical supplies came to light during the pandemic. These attitudes seem to extend into the digital sphere as well, as the ownership of TikTok by a Chinese entity has worried many Americans about their data being shared with a hostile foreign power.43

Of particular concern for the movie industry is the ownership of Legendary Entertainment by a Chinese entity. Since a sale of Legendary is likely under consideration, there is a pathway for the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (cfius) and Congressional intervention to help return the company to less adversarial hands.

This is also potentially an opportune moment to shore up intellectual property protections for American art across international territories, returning ownership to American hands and growing the domestic industry. As the American long-form entertainment market experiences continued pressure from TikTok, social media, and other alternatives to traditional movies, studios and artists alike may benefit from greater financial independence across diversified territories. This would allow creators more opportunities to take risks on original stories, including “old-fashioned” ones without flying superheroes, and without geopolitically motivated foreign investors working behind the scenes. Ensuring this financial strength for American creators requires, in part, securing their ability to realize the full value of their intellectual property in international markets, which in turn requires a more robust government enforcement apparatus for protecting digital property rights when the product is rarely a physical one. While there has been bipartisan movement in recent years to improve the regulatory situation within the United States, it is evident that more effort is needed to ensure a fair market internationally as well.

China, however, remains the most pressing front for policymakers. Hollywood may not appreciate additional scrutiny of its relationship with China, but the United States has the opportunity to protect a signature export and to stipulate sourcing parameters—while preventing its major adversary from taking advantage of Tinseltown’s exposed Achilles heel. In the words of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, “No growth without assistance. No action without reaction. No desire without restraint. Now give yourself up and find yourself again.”

This article originally appeared in American Affairs Volume VI, Number 1 (Spring 2022): 49–61.

Notes

1 Lindsay Maizland, “

China’s Repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang,”

Foreign Affairs, March 1, 2021.

2 Iain Duncan Smith MP (@MPIainDS), “Disney’s corporate policy does not appear to care about the human rights issues affects the #Uighurs…”, Twitter, October 8, 2020.

3 Rebecca Davis, “Disney Defends ‘Mulan’ Credits That Thanked Chinese Government Entities Involved in Human Rights Abuses,” Variety, October 9, 2020.

4 Ariane Lange, “Disney and Netflix Plan to Boycott Georgia over Anti‑LGBT Bill,” Buzzfeed, March 25, 2016.

5 Ross Murray, “Disney Speaks Out against Georgia’s ‘License to Discriminate’ Bill,” glaad, March 23, 2016.

6 SelectUSA, “The Media and Entertainment Industry in the United States,” accessed January 24, 2022.

7 United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World Population Prospects 2019 (2019).

8 SelectUSA, “The Media and Entertainment Industry in the United States.”

9 Box Office Mojo, “Chinese Yearly Box Office,” July 7, 2021.

10 Box Office Mojo, “Domestic Yearly Box Office,” July 7, 2021.

11 Shirley Zhao, “Hollywood Struggles for Fans in China’s Growing Film Market,” Bloomberg, February 15, 2021.

12 Box Office Mojo, “2020 Worldwide Box Office.”

13 “Ang Lee: Biography,” IMDb, accessed January 24, 2022.

14 “‘Brokeback’ Not Coming to Mainland,” China View, March 10, 2006.

15 “‘2046’ Opens in China amid Global Hype,” China Daily, September 28, 2004.

16 “2046”, IMDb, accessed January 25, 2022.

17 Ryan Faughnder, James Rufus Koren, “As China Cools on Hollywood, the Movie Business Looks Closer to Home for Money,” Los Angeles Times, November 12, 2017.

18 David Barboza and Brooks Barnes, “How China Won the Keys to Disney’s Magic Kingdom,” New York Times, June 14, 2016.

19 Erich Schwartzel, Ken Thomas, and Emily Glazer, “Disney’s Chairman Bob Iger Is Game for a New Job: U.S. Ambassador to China,” Wall Street Journal, December 17, 2020.

20 Patrick Brzeski and Tatiana Siegel, “From Deal Frenzy to Decoupling: Is the China-Hollywood Romance Officially Over?,” Hollywood Reporter, May 21, 2021.

21 “The Cost of Movie Piracy: An Analysis Prepared by LEK for the Motion Picture Association,” Wired, accessed January 25, 2022.

22 “Winter Is Coming: China’s Campaign against Film Piracy Is Upsetting Hollywood Fans,” Economist, February 18, 2021.

23 Patrick Brzeski and Tatiana Siegel, “From Deal Frenzy to Decoupling: Is the China-Hollywood Romance Officially Over?,” Hollywood Reporter, May 21, 2021.

24 “Where Is Netflix Available,” Netflix, accessed January 25, 2022.

25 Brzeski and Siegel, “From Deal Frenzy to Decoupling.”

26 Patrick Frater, “China Is Poised to Retain Worldwide Box Office Crown, While Decoupling from Global Film Industry,” Variety, December 2021.

27 Brzeski and Siegel, “From Deal Frenzy to Decoupling.”

28 Joe McDonald, “China Bans Men It Sees as Not Masculine Enough from TV,” Associated Press, September 2, 2021.

29 Frater, “China Is Poised to Retain Worldwide Box Office Crown.”

30 “Merkley, Rubio, Warren, Cornyn Introduce Legislation to Monitor, Address Impacts of China’s Censorship of Americans and American Businesses,” Office of Senator Jeff Merkley, news release, February 24, 2021.

31 Zack Sharf, “Judd Apatow Calls Out Hollywood Censorship in China: ‘They’ve Bought Our Silence with Money,’” IndieWire, September 16, 2020.

32 Zack Sharf, “Sony Boss Says Tarantino Made ‘Right Decision’ Refusing to Edit ‘Hollywood’ for China,” IndieWire, January 14, 2020.

33 Rebecca Davis, “Legendary Entertainment Hires Sirena Liu as China CEO,” Variety, April 15, 2020.

34 Davis, “Legendary Entertainment Hires Sirena Liu as China CEO.”

35 Sonny Bunch, “Opinion: China Is Turning American Movies into Propaganda. Enough Is Enough,” Washington Post, August 20, 2020.

36 Thomas Kaplan, “The U.S. Imposes—and Suspends—Tariffs on Six Countries over Digital Taxes,” New York Times, June 2, 2021.

37 David Ng, “Hollywood Studios Win as European Countries Vie for U.S. Production Dollars,” Los Angeles Times, March 20, 2018.

38 The White House, “United States Achieves Breakthrough on Movies in Dispute with China,” February 17, 2012.

39 The White House, “United States Achieves Breakthrough on Movies in Dispute with China.”

40 United States Patent and Trademark Office, “Protecting Lawful Streaming Act of 2020.”

41 Gene Maddaus, “Sen. Thom Tillis Proposes ‘Notice and Stay Down’ Rewrite of Online Copyright Law,” Variety, December 22, 2020.

42 Chloe Taylor, “‘Nightmare’ Conditions at Chinese Factories Where Hasbro and Disney Toys Are Made,” CNBC, December 7, 2018.

43 Jack Sommers, “Nearly Half of Americans Fear TikTok Would Give Their Data to the Chinese Government,” Business Insider, July 15, 2021.