Meet Walter White: once a promising chemist with a PhD from Caltech, at age fifty, he appears to be an unremarkable teacher at a public high school in Albuquerque. When he tries to offer a passionate introduction to chemistry on the first day of class, most of his students stare blankly while a few flirt in the back of the room.

To supplement his paycheck, Walt works the cash register at a local car wash after school. His domineering boss, Bogdan, occasionally sends him outside to scrub down cars. In a scene of ultimate humiliation, Walt finds himself polishing the hub caps of a Corvette owned by one of his most entitled students. “Hey, Mr. White! Make those tires shine!” the kid shouts, as Walt dutifully buffs the rims.

At home, Walter finds himself under the thumb of his wife, Skyler. He loves her but also bends to her will. The bedtime “romance,” specifically the placement of Skyler’s clenched fist, while Walt lies passively on his back, is emblematic of their relationship: Skyler has Walt’s manhood in her viselike grip. Walt’s son, Walter Junior, loves his dad. But he idolizes his “Uncle Hank,” Walt’s macho brother-in-law who works for the DEA. For Junior, Hank represents the excitement, danger, and self-assertion that is missing from Walt’s thoroughly “decent” life.

The surprise party that Skyler throws Walt for his fiftieth birthday is only another source of alienation. Exhausted from his indignity-filled day, he opens the door to the synchronized “surprise!” of Skyler, her sister Marie, Hank, Junior, and what seems to be the whole neighborhood packed into his living room. As the guests mill about, drinking white wine dispensed from party-sized cardboard boxes, Walt is stuck making small talk. Suddenly Hank announces that a special on the Albuquerque DEA is about to air on the evening news. The guests crowd around the television set to watch Hank and his men busting up a bunch of methamphetamine labs. Walt is left standing alone.

The next shoe to drop for Walter—a terminal cancer diagnosis—seems just the endpoint of his ill-starred fate. As he’s scrubbing down cars after his birthday, Walt suddenly collapses. In the back of the ambulance, he quickly regains consciousness and begs the paramedics to release him: “It’s just some bug going around . . . just like a chest cold . . . could be some low blood sugar as well . . . I didn’t have the greatest breakfast this morning, honestly.” But after a lengthy exam, Walt gets the bad news. As the doctor delivers his diagnosis, Walt hears only a blur of undifferentiated noise. “You understood what I just said to you?” asks the doctor earnestly, noticing Walt’s apparent lack of attention. “Lung cancer. Inoperable. Best case scenario with chemo, I’ll live maybe another couple years,” Walt replies indifferently. “It’s just . . .” he continues, “you’ve got mustard on your [shirt].” Walt’s range of focus epitomizes his resignation. His life is becoming a morass of accidents.

Making Sense of Walter White as Hero

Thus begins Breaking Bad, AMC’s smash-hit TV series that took America by storm, becoming one of the most watched shows on television between 2008 and 2013 and winning sixteen Emmy Awards. The show tells the story of Walter White, beleaguered chemistry teacher and browbeaten husband, who, on death’s door, makes a life‑changing career shift of the most improbable kind: he puts his chemistry expertise to work as a methamphetamine “cook” and quickly rises to prominence in the kill-or-be-killed world of drug dealing along the southwest border.

On the one hand, it’s not difficult to make sense of the show’s appeal. It’s a thrilling postmodern take on the western—darkly comical, vividly shot, and filled with shocking twists. On the other hand, Breaking Bad presents a difficult puzzle: why do we find ourselves rooting for such a morally compromised protagonist as Walter White? Walt doesn’t just break the law. He makes a living ravaging people’s lives by selling them meth. Although he enters the drug trade to provide for his family, he continues in it for his own gratification. As he rises to prominence, he treats his rivals brutally and even harms the innocent to his advantage.

And yet, there’s something we admire in Walter White, even as he goes further and further down the path of “breaking bad.” Somehow his acts of injustice are not enough to turn us against him, at least not entirely. After all is said and done, Walt stands as a folk hero in American culture. Today his portrait is still glorified on T-shirts and bumper stickers. His characteristic “Heisenberg hat,” which he dons for crucial showdowns with foes throughout the series, is a popular novelty item. One could almost say that Walter White is for American pop culture the kind of representative hero that Achilles was for ancient Athens. But Walter White, high school chemistry teacher turned meth dealer, is hardly a hero in the Homeric sense. In what, then, does his heroism consist?

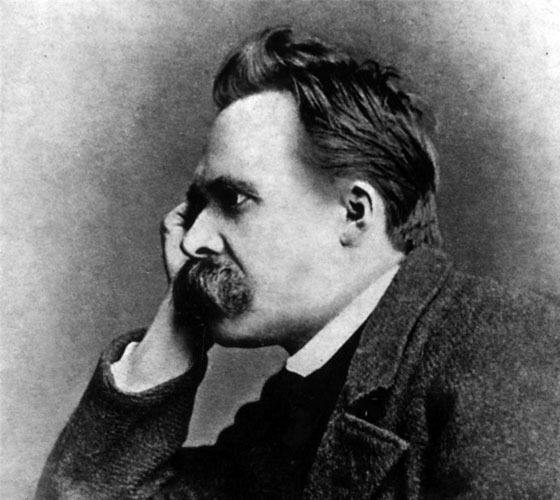

I would argue that Walter White is a thoroughly Nietzschean hero, one of the few compelling examples of such figures that American culture has ever produced. It was the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche who foresaw the predicament of Walter White, and of modern society, with uncanny clarity: We who inhabit modern societies are prone to a characteristic weakness, a pusillanimity in the face of the petty conventions and preoccupations of bourgeois existence. The fundamental challenge is to fashion a life that overcomes this debased condition, to rise from “last man” to “overman.” Some think that Nietzsche’s overman is an immoral, power-driven tyrant, who overcomes conventional morality by asserting a nihilistic will to power. But this is a misreading. Nietzsche’s overman rises above conventional morality not by embracing nihilism but by forging a narrative coherence to his life that issues in a kind of empowerment, or self-possession.

The appeal of such empowerment, and of a hero who strives for it, is especially strong at this moment. In postrecession America, there is a mounting desire to throw off the straitjacket of a self-serving upper-middle-class morality that valorizes the sanctity of law and of “playing by the rules.” In many circles, there is a growing sense that the system is rigged, that the rules and conventions in place, defended in the name of fairness, efficiency, safety, or “win-win” economic arrangements, serve to empower some at the expense of others. Many find themselves enmeshed in absurd bureaucratic hierarchies—in work and in everyday life—that afford scant grounds for self-possession or self-respect.

At the same time, there is a widespread sense that the “legitimate” economy fails to reward the effort and talents that ordinary people devote to their jobs. Instead, it heaps benefits on those who are simply lucky, or who manipulate the system, or who have a knack for getting rich off other people’s work (sometimes ruthlessly) while operating within the bounds of the law. People find themselves increasingly in the condition of Walter White—mired in routines of work that do not call forth their potential or accord them much dignity. Like Walt, many find themselves struggling to be recognized for the work they do, on the job or at home. It is against this cultural backdrop, I believe, that Breaking Bad still captivates public attention and illuminates the anxieties of our time.

Nietzsche helps us interpret the improbable life story of Walter White and understand how Walt came to represent a kind of hero for this moment. Walt’s turn to crime is not simply a desperate move that spirals out of control—rather, it is a story of empowerment. In “breaking bad,” Walt rises to self-possession from a contemporary form of malaise and despair.

Nietzsche also helps us understand the kind of self-possession Walt gains. On the surface, Walt’s trajectory might seem to suggest a grim, nihilistic drive to self-assertion through conquest: the way to truly live is to reject the social order in which you find yourself stifled and adopt a self-serving “live your own way” ethic. But this reading of Walter White is misguided. Walt does not simply despair of humanity and become a scornful manipulator of society who only enjoys domination over others. He is not the archetypal nihilist—like Roskolnikov from Crime and Punishment or Malvo from the recent TV series Fargo—who seeks destruction for its own sake. What makes Walt a complex protagonist, and what makes his trajectory moving, is that his “breaking bad” constitutes an attempt to forge a narrative coherence to his fractured and nearly expired life.

Walt’s rise to power in the meth business can be understood, in Nietzschean terms, as an attempt to “redeem the past,” to reclaim a coherent whole out of the disparate parts of his life: his role as chemist, entrepreneur, husband, father, and even teacher. The self-possession for which he strives is thus bound up with a totality of commitments that cannot be captured by simple notions of egoism, selfishness, and conquest.

Breaking Bad and Nietzsche

Nietzsche helps us diagnose the initial predicament of Walter White as the condition of the “last man,” a degenerate state of existence that Nietzsche identifies as pervasive in modern life. The last man, writes Nietzsche, enjoys “a little pleasure by day, and a little pleasure by night,” but always “with a regard to health.” The last man “has left the regions where it was hard to live” and ekes out an easy but hollow existence aimed at an ever-receding vision of repose. Absent from his life is any risk, adventure, or ambition: “‘What is love? What is creation? What is longing?’ Thus asks the last man, and he blinks.”1

Walter White is the last man, or very close to it. He is confined to a “little pleasure by day”—the breakfast of eggs, veggie bacon, and echinacea that his wife Skyler prepares for his fiftieth birthday—“a little pleasure by night”—the dispassionate, almost clinical hand job that she administers like medicine before bed—and all “with a regard to health.”

Nietzsche’s “last man” captures a condition to which every life is susceptible. As we sympathize with Walter White, we acknowledge the possibility of the last man in ourselves. In one way or another, we’ve all been there before—in moments of enervation, lack of gumption, obsession with health, safety, and a long life, or earnest submission to the so-called necessities of a bourgeois existence. One of the brilliant conceits of Breaking Bad is its relentless exposure of the petty officiousness and stifling moralism of middle-class suburban life. The show constantly juxtaposes Walt’s harrowing travails and frank self-assertion in the underworld with the quotidian concerns and vapid, impersonal niceties of the law-abiding community.

In extricating himself from the condition of the last man, Walt does not merely oppose his oppressive world with an angry “No!” He finds direction and rises to a kind of virtue that comes to light in Nietzsche’s conceptions of the “overman” and the “will to power.” Unfortunately, these key concepts are as liable to misinterpretation as Walter White himself. Due to misleading ideological appropriations of Nietzsche, and careless readings of his provocative aphorisms, we have a caricature of the “overman” as a kind of nihilistic lover of conquest who is above all ethics. But even a cursory reading of Nietzsche reveals a different conception. Even in his most “polemical” treatments of morality, as Nietzsche calls them, he makes clear that he seeks to promote one ethical framework over another, not to reject ethics in favor of “might makes right.” He seeks to replace a morality of weakness, timidity, and resentment with a morality of self-command.

A first approximation of what Nietzsche means by “overman” is the passionate pursuit of life as an unfolding story: “What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not an end.”2 “Overman” is meant to point away from the “end,” the goal, the accomplishment, and toward the way. Life, Nietzsche suggests, is a ceaseless process of self-overcoming.

“Overman” can thus be seen as a corrective to our “results-oriented” culture that interprets power as the capacity to get things done, to attain a certain standard of living, and to “make the world a better place.” To this extent, Nietzsche’s notion of overman is radical and perhaps unsettling. Nietzsche sees in our obsession with accomplishment and progress a certain folly. He takes aim at the Enlightenment view of providence that comes to paradigmatic expression in Marx: the notion that humanity, through the technological mastery of nature, can solve the problem of scarcity and, through the attainment of a universal consciousness free of class difference and exploitation, bring about the perfectly just world.

Against this view, Nietzsche tirelessly reminds us of our mortality. The ultimate oppression of existence is not economic exploitation or political injustice but our subjection to death. Death is not merely physical. It cannot be postponed by medical intervention or life extension technology. Death has to do with the passage of time, the inescapable fact that today becomes yesterday—that action, on the one hand, cannot be undone and, on the other, cannot be relived. The deepest source of human suffering is that missteps perpetually haunt us and shimmering moments fade away.

In such a universe, the virtues of striving toward definite goals, no matter how noble, go only so far. Nietzsche is not opposed to curing disease, feeding the hungry, or fighting for justice. But he suggests that charitable aims, if glorified as the heights of virtue, obscure a deeper, more significant moral project: that of maintaining and forging a narrative coherence to one’s life against the twists and turns of an unfathomable fate.

Nietzsche points away from an ethic of progress and towards an ethic of what could be called redemptive integration: “And this is all my creating and striving, that I create and carry together into One what is fragment and riddle and dreadful accident. And how could I bear to be a man if man were not also a creator and guesser of riddles and redeemer of accidents? . . . To redeem those who lived in the past and to recreate all ‘it was’ into ‘thus I willed it’—that alone should I call redemption.”3

Nietzsche’s notion of redemption belies the simplistic notion of “will to power” as a destructive force contemptuous of history. “Will to power” is quite the opposite: the creative striving for totality or “wholeness” within a universe vulnerable to dispersion and decay. Failure, decay, calamity—death—is not final. It’s a moving force—a riddle—an invitation to think, and learn, and rise to self-possession. It is on us to make the past our own, to draw lessons and insights for action here and now from the people and events of old.

But redeeming the past is hard. Finding ourselves too weak to face our suffering and make something of it, we often flee from the task. We divert ourselves with ingenious strategies of flight from suffering: resignation to a life of end-of-history repose; cynical indulgence in easy pleasure, justified as the “rational way” in contrast to the futility of grandiose projects; wry distance from all commitment, valorized as the “enlightened” view that roles and loyalties are mere conventional nonsense; furious vengeance that seeks to inflict harm on someone else, all for the loss that one suffers and is too weak to redeem; stern moralism that calls all these things virtuous, while condemning any challenge to the last man’s comfort.

It is within this Nietzschean framework of virtue and vice that I propose to understand Walter White. Walt’s “breaking bad” is not a nihilistic turn to criminality out of despair. His ascent in the meth business is rather the fulfillment of a narrative in which he attempts to carry “together into One” the aspects of his life that are at first “fragments and riddles and dreadful accidents.”

The gravity, and the humor, of Walt’s transformation is that it redeems his lackluster past rather than rejects it. At the height of his power, Walt even rejoins the car wash—the scene of his early humiliation and the site of his initial collapse from lung cancer. Now, with his pile of ill-gotten but hard-earned cash, Walt edges out his former boss, Bogdan, and purchases the car wash as a money laundering business. But even as boss, Walt finds himself, at times, behind the cash register once again, hawking pine-scented air fresheners to customers. But such mundane salesmanship is no longer an expression of alienation and powerlessness; it is a wry cover for his secret life of influence and consequence.

One could imagine forms of Nietzschean empowerment that do not involve a turn to crime. Nietzsche himself reserves his greatest esteem for philosophical figures, such as Goethe.4 His prophetic hero, Zarathustra—part lone adventurer, part devoted teacher—is a “criminal” only in the Socratic sense of someone who refuses to follow conventional wisdom. Zarathustra furthermore espouses the power of ideas over force: “thoughts that comes on doves’ feet guide the world.”5 His greatest victory is learning to laugh, not fight.6 But that Walter White empowers himself through crime is no accident within the Nietzschean framework. Central to Nietzsche’s critique of bourgeois existence is a critique of the law and of law-abidingness. To valorize the sanctity of law, to put great stock in “playing by the rules”—and to condemn others for breaking them—is to adopt a self-aggrandizing stance akin to that of the criminal. The champions of the rule of law, Nietzsche suggests, would turn to crime without compunction if they were brave enough and stood to gain. (“They would be pharisees, if only they had—power.”7) Breaking Bad relentlessly develops this insight, bringing to light familiar instances of the law as absurd and oppressive—illustrations of petty power dynamics.

It’s worth considering just a few examples: “The law” is the federal bureaucrat who officiously grills Hank about being off duty after Hank shoots and kills Tuco Salamanca, a brutal and psychopathic meth dealer. “The law” is the heavy breathing of the Albuquerque high school PTA, and their moralistic demand for tighter background checks of school employees, after they learn that one of the janitors, a hard-working and compassionate man, was caught with a single marijuana joint in his home. “The law” is the doctor who insists, in line with “protocol” and against Walt’s wishes, that Walt remain in the hospital and receive psychiatric counseling until they discover the source of his mysterious “fugue state.” (Walt had faked a brief psychological breakdown to account for his absence from home while making meth.)

In a world in which the law is a tool of petty dominion, being a person of self-possession, judgment, and efficacy almost inevitably means “breaking bad”—in some way or another. The show is replete with characters who, like Walt, are able to find agency only at the margins of legitimate society, or simply in the criminal world. The most striking example is Walt’s lawyer, Saul Goodman (now protagonist of the successful Breaking Bad spin-off series Better Call Saul). Having found himself disempowered and demeaned in the legitimate role of public defender, Saul has reinvented himself as a “criminal” lawyer in the double sense of the word. His official job is defending small-time crooks and deadbeat accident victims. His real work is wheeling and dealing for black market operators like Walt—helping them launder their money or make connections in the criminal underworld. The irony is that Saul’s operation, which straddles the worlds of legality and crime, really does provide the “marginalized of society” with a vigorous legal defense. Armed with street knowledge, the Bill of Rights, and the occasional piece of incriminating evidence from his underworld associates, Saul rushes to the aid of suspects before they can be strong-armed into a confession by the DEA. Oddly enough, Saul is more effective in upholding the law as a criminal than as a legitimate attorney. Such paradoxes force us to consider the extent to which self-possession and “breaking bad” go together.

Walt’s “Breaking Bad”

At the moment of his cancer diagnosis, Walter White is on the brink of resignation. He can find in his life hardly a purpose, aim, or ambition that his cancer diagnosis might thwart. His humanity seems to be expiring faster than his disease-ridden lungs. But Walt is not yet the last man. At the beginning of the first episode, before the twists and turns of his ill-fated day, we see him gazing wistfully at the impressive degrees and awards on his bedroom wall, as he walks monotonously in place on a miniature stair-master. (The symbolism is heavy.) We learn soon after that Walt once founded a chemical company, “Gray Matter,” with two friends from graduate school, Gretchen and Elliot Schwartz. For reasons that are never fully clear, Walt had a falling-out with his partners and sold his share in the company at an early stage. Since then, the company’s stock has soared. Gretchen and Elliot have millions (thanks to Walt’s groundwork) while Walt has nothing—or almost nothing. Walt still has a memory of his life of promise and ambition.

In his wistful gaze, in his objection to scrubbing the cars, and in the pedagogical scolding of his students, Walt still sighs a breath of life. Unlike the last man, who takes spurious pride in his enfeebled condition, rationalizing it in all sorts of ways (as “tranquil,” “content,” “secure,” and so on), Walt knows he is capable of something more. The cancer diagnosis, which threatened to break his will, leads him instead to “break bad.” Like Nietzsche’s image of the “preying lion,” who rejects “though shalt” and finally says “I will,” Walt, in a whirlwind of profanity, quits his job at the car wash.8

At first Walt attempts to exert his newfound self-possession through expanding his rejection of Bogdan to the whole of his life. Walt says “No!” to his cancer treatment. His “No!” is his first rejection of the law, in this case, the unwritten convention that one gets treated, no matter how grave the diagnosis. (Skyler, Junior, and Hank impose this law in a humiliating family intervention.) But unlike the last man who attempts to extend his life by all means (“the last man lives longest”9), Walt values his self-possession above mere existence: “the doctors talk about surviving, like it’s the only thing that matters. . . . But what I want . . . what I need, is a choice . . . sometimes I feel like I never make any of my own . . . my entire life, it just seems I never, you know, had a real say about any of it . . . now this last one, cancer . . . all I have left is how I choose to approach this.” Motivated by a resurgent but still enfeebled will to power, Walt, in Nietzsche’s terms, would “rather will nothingness than not will.”10 But when he wakes up the next morning to find Skyler sorrowfully preparing breakfast alone in their kitchen, he gives in to her once again. He resolves to get treated.

Soon thereafter, however, in a most unlikely way, Walt begins to rediscover purpose in his life. After learning from Hank of the money to be had in the meth business, Walt is intrigued. Through a chance encounter, he teams up with a former student and small-time dealer, Jesse Pinkman, to try his hand at making and selling meth. As he discovers his skill in the illicit trade, and begins to earn respect in the underground of Albuquerque, Walt makes a miraculous recovery from his supposedly terminal and crippling illness.

From Angry “No” to Exuberant “Yes”: Walt’s Redemption of His Past

Walt’s foray into the drug trade soon takes him far beyond his initial goal of providing for his family after his death. Selling meth turns out to be an expression of the will to power: a drive to “to something higher, farther, more manifold.”11 The danger of the drug trade, the threat of jealous competitors, the tenacity of the DEA bent on catching dealers, and the difficulty of securing the ingredients and equipment to manufacture top-of-the-line meth perpetually test Walt’s resolve and wits. The drug trade turns out to be a high-stakes platform on which Walt can exercise the chemical expertise and strategic wit that languished in his role as a high school chemistry teacher. It is also a platform on which Walt earns notoriety with his competitors and the DEA as the mysterious “Heisenberg”—a pseudonym that he adopts as a cover and maintains as a mark of pride. (By naming himself “Heisenberg,” after the world-famous physicist, Walt also asserts himself as a scientist of prestige.) Long after Walt has earned enough money to support his children, he finds himself perpetually in search of ways to expand his prowess as drug lord. At the height of his power, in response to Jesse’s suggestion that they finally sell the meth business, Walt proclaims, “I am not in the meth business. I am in the empire business!”

But what makes Walt’s “empire” exemplary of Nietzschean will to power is that it transcends the drug trade. Walt’s dominion, so to speak, consists in the balancing act of commitments that makes him a someone, a self, and not a mere plaything of disparate forces. The three commitments, the redemption of which lies at the heart of his self-transformation, are his role as a chemist, family man, and teacher. In bolstering and shaping each other, these commitments represent the kind of narrative “whole” that, for Nietzsche, constitutes a person of integrity.

Walt as Heisenberg

As Heisenberg, creator of an exceptionally pure blue meth and architect of an elaborate manufacturing and distribution network, Walt recaptures the expertise in chemistry and entrepreneurship that he allowed to atrophy after separating from his former business partners Gretchen and Elliot. In rejecting the label of the “meth business” in favor of the “empire business,” Walt asserts his desire for rule over profit. The tenacity with which Walt pursues and expands his empire is not born of rational calculation, financial greed, or even a desire for respect in the abstract. It is about fulfilling a concrete narrative of redemption that draws together the fragments of his past. The meth trade is an expression of who he is, a standpoint from which he can look back on his life with pride and not regret. After years of being relegated to the beakers, flasks, and Bunsen burners of a high school science lab, Walt now operates within a state-of-the-art arrangement of tanks and vats and ventilation systems befitting a high-level industrial chemist. Previously, his measurements and instructions went in one ear and out the other of his inattentive students; now they are for the sake of making something—and making it exceptionally well.

Although Walt has nothing but disdain for using meth, he takes immense pride in cooking it to perfection. Understandably, Walt is unwilling to forfeit the position he has attained—even for immense profit. He can’t bear the thought of someone else, who cares only about the bottom line, taking up his invention. Blue meth will stand or fall with him.

From Browbeaten Husband to Committed Provider

Insofar as Walt cooks to support Skyler, Junior, and his infant daughter, his meth business is tied to family from the start. But what begins as a relation of means to ends turns into something more. Cooking and selling meth turns out to be an activity, with its own claims, through which Walt recaptures the very significance of family. Through his activities outside the home, Walt attains a distance from Skyler and Junior that actually strengthens his commitment to them. Cooking meth with Jesse Pinkman in a stifling RV on the arid outskirts of Albuquerque, Walt achieves freedom from Skyler’s heavy-handed love and Junior’s naive admiration. As he breaks a sheet of crystal clear methamphetamine at the end of a hard day’s work, he affirms himself as a provider for his family rather than an object of their pity.

With his new role comes a new take-charge attitude around the home. Upon returning to bed with Skyler after his harrowing first cook with Jesse on the outskirts of town, Walt’s spirits are high. In a sudden reversal of roles, he for once initiates the nighttime romance. “Walter!” Skyler exclaims in disbelief at his advance, “Is that you?!” Her comical expression of surprise attests to Walt’s incipient transformation. Cooking meth has forged a meaningful distinction in his formerly one-dimensional life. In relation to his nail-biting day of work, including a near-death encounter with two of Jesse’s former associates, and a close call with the cops, Walt’s return home at the end of the day takes on a new meaning. No longer is it the confrontation with yet another realm of disempowerment. It is rather the entry into a haven of security and respite of which he is the custodian.

Walt’s newfound agency also finds expression in his relation to Junior. Whereas before he left Junior’s upbringing and discipline to Skyler, who would fret over mundane suspicions, such as whether Junior might have smoked a joint, Walt now claims an active role for himself. One day, for example, after Skyler leaves the house, Walt takes Junior out for a driving lesson. When Walt sees Junior, who struggles with cerebral palsy, using both of his feet to drive (one over the gas, the other over the brake), Walt intervenes to correct him. “Dad this way is easier,” Junior responds. Instead of thoughtlessly capitulating to his son as Walt would have done in his days of resignation, he holds firm: “There’s the easy way, and then there’s the right way,” he tells Junior. “Your legs are fine. You just have to stick with it. Don’t set limits for yourself, Walt.” By addressing his son by his own name, “Walt,” rather than by Junior, or by “Flynn” (the name that Junior, in a mildly rebellious manner, has decided to adopt), Walt at once identifies his son as his own and directs the firm words of advice to himself. Walt has decided to live the “right way”: the life of self-responsibility.

Unfortunately for Walt, his can-do attitude around the house does not win him favor with Skyler. She begins to see his eagerness to cook breakfast, clean the dishes, take Junior to school, and replace their old water heater as a way of deflecting attention from his mysterious and increasingly frequent comings and goings. For obvious reasons, Walt tries to hide his illicit business from Skyler. But the secret is hard to keep, and Skyler gradually becomes suspicious. Soon she can’t bear Walt’s furtiveness. But what she really can’t bear, which becomes clear as the show unfolds, is Walt’s newfound self-possession.

When Walt was the earnest and meek husband who allowed Skyler to rule the roost with impunity, she was all smiles and love. But as soon as Walt begins to assert himself in the home, she withdraws her affection. When she wakes up one morning to find Walt busy at work, installing the much-needed heater and removing rotten wood boards from the closet, she turns chilly rather than grateful. Although she can’t quite come out and say it, she sees his work as usurping her prerogative to fret about their budget and to issue edicts on hot water rationing.

When Skyler finally discovers that Walt is selling drugs, she summarily boots him from the house. The severity of her response—not even giving her loyal husband of twenty years a chance to account for his actions—speaks to her resentment of his newfound agency. Here we see the Nietzschean critique of moral hypocrisy on full display. Skyler’s concern for the family, which at first seemed admirable, turns out to be a form of petty self-assertion.

That such resentment, and not respect for the law, or love for the family, is really at play in Skyler’s rejection of Walt is made clear by the vindictive tryst she has with her boss, Ted Beneke—an apparently squeaky-clean man who, with a forced coolness and sanctimonious bearing, is cooking the books on his floundering business—the aptly named “Beneke Fabricators.” With full knowledge of Ted’s white-collar crime, Skyler jumps into bed with him to get back at Walt. Her vengeful affair with Ted brings to clear expression the enfeebled will to power that had been latent in her apparently loving action.

As the story unfolds, we discover that what Skyler really wants is not for Walt to stop selling drugs, but for him to grant her a role in the illicit business. She eventually accepts him back into the home and offers to help him conceal his ill-gotten gains from the IRS. Just as Walt had put his chemistry expertise to work on cooking blue meth, Skyler puts her accounting skills to work on laundering dirty money—in effect, Skyler and Walt reunite as partners in crime. The precarious nature of their relationship throughout the show has to do with who calls the shots.

But even as tensions flare in the home, Walt’s commitment to Skyler remains strong. Aside from a woefully inept and unsuccessful romantic advance on his boss at the high school, Principal Carmen (a desperate grasp by Walt for self-assertion while Skyler is cavorting with Ted Beneke), Walt remains faithful to his wife. Never once does he consider giving a dime of his earnings to anyone but her and the kids. Walt provides for Skyler and his family even when they reject him.

In a dramatic shift of disposition as he rises to power in the drug trade, Walt turns from shame and apology in the home to mercy and forgiveness. “I forgive you,” Walt says to Skyler in reference to her affair with Ted.

Although the home is never simply tranquil for Walt (it is always imbued with the power struggle between him and Skyler), it becomes a realm of comparative serenity, especially after Walt’s daughter is born. Time and again, we see Walt cradling his daughter with genuine love and pride just before or after some harrowing experience or terrible injustice he commits. We realize that Walt’s reinvigorated loyalty to family is intimately connected to his trials and travails in the drug world. Whereas before, Walt maintained a deferential “decency” to friend and foe alike, he now treats different people differently. He realizes that to be a loving father and tenacious provider means to draw a distinction between family and other realms of life.

Walt as Mentor to Jesse Pinkman

Of all the roles that cooking meth might strengthen, being a devoted high school teacher and mentor seems most unlikely. (Teachers are supposed to keep kids away from drugs, right?) But the comedy and drama of Breaking Bad consists, in large part, of Walt’s recapturing his role as a teacher. Although Walt is eventually fired from his job at the Albuquerque public high school, he recreates his pedagogical role in the partnership with Jesse Pinkman.

Pinkman, now age twenty-five, was a former student of Walt who had miserably failed his chemistry class. Pinkman is the quintessential ne’er-do-well student who contributed to the emptiness of Walt’s work. But through a chance encounter (Walt spots Jesse tumbling, half naked, out of a second story window to evade a DEA drug bust), the two team up as unlikely partners in crime. (Walt initiates the partnership by threatening to give Jesse over to the DEA unless Jesse helps him sell meth.) What begins as a partnership of utility (Walt knows the chemistry; Jesse knows the drug trade) turns into a relationship of teacher and student. Although Jesse is now in a position of quasi-leadership, in charge of introducing Walt to the drug trade, he still calls him “Mr. White.” Notwithstanding his recalcitrance at Walt’s tough love, Jesse looks up to Walt as the mentor he never had.

For Walt, Jesse is the student he never had, the redemption of his ill-fated career at Albuquerque High. Whereas in high school, Jesse regarded Walt as a total nerd and stiff (we at one point see the mocking cartoons of Walt that Jesse drew in class), he now appreciates him as a master chemist. “Yeah, Science!” Jesse exclaims in awe of the “pure glass” that Walt cooks on his first try. Jesse eventually absorbs and applies Walt’s chemistry lessons in the meth lab. At first motivated solely by the prospect of making “fat stacks” of cash, Jesse begins to take pride in his own skill at cooking Walt’s recipe of meth. Jesse thus makes good on the frustrated comment that Walt once wrote on one of Jesse’s failed high school exams: “Apply yourself!” In Jesse’s success, Walt can see an image of himself: not only of himself as a successful teacher, but as someone who has emerged from the depths of malaise and despair.

The relationship between Walt and Jesse is far from easygoing. Walt finds himself in a perpetual tussle with Jesse over when and where to cook and who is responsible for what. Walt is constantly getting the pair out of jams due to Jesse’s carelessness, indiscipline, and bouts of drug use. But throughout their travails, Walt and Jesse maintain a friendship that transcends the bottom line of their meth business.

As their friendship develops, Walt even begins to regard Jesse as a second son, the son who knows the tenacious and daring side of him that Junior does not. Walt can reveal to Junior something of his newfound agency only through the distorting medium of mundane gestures of bourgeois agency, such as replacing the rusty old water heater and buying Junior a Dodge Charger with bright red stripes.

To make matters worse, such expressions of agency are overshadowed by the self-deprecating façade that Walt has to maintain as a cover for his life of crime. To prevent Junior (and others) from knowing of his illicit activities, Walt at first pretends to be receiving financial support for his cancer treatment from Gretchen and Elliot (former business partners who may have ripped him off). In a kindhearted but naive gesture to supplement the support, Junior starts an online charity fund entitled “Save Walter White.” On the home page is a large photograph of Walt’s face plastered with the reticent smile that characterized his former life of meekness and resignation. Unbeknownst to Junior, Walt, with the help of his newly acquired lawyer, Saul Goodman, arranges for his drug money to be filtered piecemeal into the “Save Walter” fund. So much money pours in from all over the world that a local news team comes to the house to interview Junior on his father: “He’s a good man, isn’t he?” asks the reporter. “Absolutely,” replies Junior. “Ask anyone, anybody . . . he’s just decent . . . and he always does the right thing.” Junior’s praise, though thoroughly genuine, gives voice to precisely the qualities of character that Walt loathes in himself and is beginning to overcome. “Decency,” after all, is Junior’s naive interpretation of what had really been weakness.

Jesse Pinkman: Focal Point of Walt’s Narrative Whole

But Walt’s relationship with Jesse Pinkman is different. Walt is even willing to put his life on the line for his partner. Perhaps the most significant expression of Walt’s loyalty to Jesse is his tenacious insistence upon keeping Jesse as a lab assistant against the wishes of the indomitable Gustavo (“Gus”) Fring—the high-powered drug lord Walt comes to work for in season three.

Gus, a Chilean immigrant to Albuquerque via Mexico, is a quiet but commanding figure who has climbed the ranks of the drug trade and now rules the southwest territory with seemingly unshakable calm, precision, and care, under the ironic cover of the fast-food chicken franchise “Pollos Hermanos.” The franchise, in turn, is owned by Madrigal, a multinational corporation based in Germany that also supplies Gus with the chemicals for making meth. Like Beneke Fabricators, but on a far grander scale, Madrigal embodies the hypocrisy of the “legitimate” world. On the outside, Madrigal is a squeaky-clean operation run with German efficiency and scruples. Just below the surface, it’s in cahoots with a big-time drug dealer.

Like the car wash that Walt owns to launder his money, Pollos Hermanos brings to clarity the Nietzschean juxtaposition of suburban “service with a smile” and the life-and-death judgment of the drug trade. The underworld quite literally seethes beneath the kitsch and rote friendliness of Pollos Hermanos.

By day, Gustavo Fring works diligently in a perfectly pressed manager’s uniform behind the counter, overseeing food preparation and customer service. He even sponsors charity “fun runs” in support of the Albuquerque DEA. Like Walt, he is fluent in the impersonal happy talk of the town and able to ingratiate himself with the utterly credulous community. By night, he carefully plots his next move against the Mexican Cartel, which is perpetually threatening to encroach upon his territory.

Among many rules of the business to which Gus abides is “never trust a drug addict.” After one look at Jesse Pinkman, whom Walt proposes as his lab assistant, Gus detects irresponsibility and risk. Thinking that Walt will replace Jesse, he offers Walt a new lab assistant, Gale Boetticher, a PhD chemist who will follow Walt’s orders perfectly. On the first day of work, Gale greets Walt at the lab with a cup of morning coffee, brewed with the utmost chemical precision to reduce the tannic acid. With the same expertise, Gale does everything that Walt asks during the meth cook. If Walt’s goal were simply to cook pure meth, establish good relations with his new boss, and earn millions of dollars, he would have accepted Gale in a heartbeat while ditching Jesse. But Walt has other purposes. Jesse’s flaws notwithstanding, Walt wants to work with his student, partner in crime, and adopted son. He insists that Gus replace Gale with Jesse.

Tensions come to a head, however, when Jesse decides to take revenge on two of Gus’s street-level drug dealers. The dealers, Jesse discovers, had used an eleven-year-old child to murder one of Jesse’s friends over a territory dispute that occurred before Walt and Jesse worked for Gus. After Gus learns of Jesse’s plot to kill the dealers, he tells Jesse to stand down. In return for Jesse’s guarantee that he will not take revenge, Gus promises that the dealers will no longer use children to do their dirty work. But instead of freeing the child from their service, the dealers murder him. When Jesse learns of the murder, he accosts the dealers at night with a gun in hand, intending to shoot them down. The dealers draw as Jesse does. Out of nowhere, in an ultimate display of loyalty to Jesse, Walt (who has followed Jesse) plows his car into the two thugs, killing them both.

The next day, Walt confronts Gus to explain himself. Instead of issuing yet another characteristic apology (in his days of resignation, Walt found himself apologizing all the time to just about everyone in his life), he stands by his deed: “I saved [Jesse’s] life. I owed him that.” Walt proposes that they consider this just one kink in an otherwise fruitful relationship of mutual respect.

Needless to say, Gus is furious that Walt would disobey his orders. Just barely containing his anger, Gus expresses disbelief at how foolish Walt could be: “No rational person would do as you’ve done. . . . Some worthless junkie [Jesse] . . . for him you intervene and put us all at risk?” But for Walt, the deed makes perfect sense—not as a move that is safe, or in the interest of profit, but as a judgment that asserts his newfound self-command. What Gus fails to see, and never fully realizes, is that Jesse, for Walt, is the point at which his role as a provider, mentor, teacher, father, and drug lord find expression. In defending Jesse, Walt is defending the narrative arc of his own life.

Walt’s act of loyalty toward Jesse turns out to be the first step on a tortuous path that leads to the assassination of Gus and the takeover of his empire. Exploiting Gus’s one weakness—his thirst for revenge—Walt is able to lure him to an ambush at the incongruously named “Casa Tranquila,” a nursing home where Gus occasionally goes to torment a former archnemesis from the Cartel. With help from Gus’s aged nemesis, Walt rigs a remote-controlled bomb to the underside of his wheelchair. When Gus comes to taunt his rival one last time before killing him, the bomb detonates. From out of the flames and pitch-black smoke, a seemingly invincible Gus shockingly emerges, half of his face blown off, the other intact. He stands up tall, straightens his tie one last time, and falls dead.

Gustavo’s gruesome disfigurement might well represent the double life that he—and Walt—have led: law-abiding decency, the human façade they turn to the public, on the one hand, and criminal self-assertion, the ghoulish face stripped bare, on the other. But it might also represent another double life, a struggle internal to both men and “beyond good and evil.” Perhaps the menacing bare-boned skull represents the spirit of revenge, and the human face the spirit of redemption.

When the news of the explosion hits the airwaves, Skyler, who by this time knows of Walt’s meth dealing, calls Walt to ask if he knows what happened. In contrast to his usual long-winded prefabrications, characteristic of his bumbling duplicity and weakness, he answers in two words: “I won.”

Walter White’s victory over Gus Fring, arguably the apex of the show, concludes season four. By this point, Walt has made the more or less full transformation from “last man” to “overman.” In the fifth and final season, Walt to some extent unravels as a Nietzschean hero. Though for a time he extends his drug empire in proportion to his newfound self-command, he gradually succumbs to a feverish desire for expansion fueled by resentment and vengeance (the very vices that Walt had exploited in Gus Fring). Perhaps not by accident, the corruption of Walt’s Nietzschean integrity leads him to an ill-fated partnership with a neo-Nazi gang. (The coincidence is striking in that a certain corruption of Nietzsche’s philosophy abetted the actual Nazi movement.) Walt initially hires the gang to assassinate a bunch of his rivals—more out of vengeance than prudence or necessity. But the gang eventually turns on Walt. They take over his empire, steal his money, and imprison Jesse Pinkman to cook meth for them. In the midst of it all, Walt is exposed to the DEA and forced to flee Albuquerque. But at the end of the fifth season, Walt returns to destroy his enemies and reclaim his life’s work.

In a bloody final battle, he assassinates the neo-Nazi thugs and frees Jesse. He also forces Gretchen and Elliot (his former business partners) to accept his drug money and funnel it piecemeal into a charity that will support Skyler, Junior, and the baby, for the rest of their lives. Walt thus returns to the narrative “whole” that constitutes his self-possession. He makes good on his role as a provider, redeems his relationship with Jesse, and renders Gretchen and Elliot his employees.

But Walt’s quintessential final act—the one that speaks most powerfully to his Nietzschean strength—comes “on doves’ feet,” as Zarathustra would say. It is far less conspicuous than the violent takedown of the neo-Nazi gang. The culminating moment in Walt’s transformation from last man to overman is one that brings to conscious expression his sense of purpose for the first time. Before embarking on his bloody last battle, he returns to Skyler for a “proper goodbye,” to say his piece and make amends. We expect one of his typical over-the-top apologies, only this time for the myriad disasters in his wake, followed by the qualification that he “did everything for the family.” As he begins his characteristic preface, “All the things that I did, you need to understand—” Skyler interrupts: “If I have to hear one more time that you did this for the family. . . . ” As if Skyler hadn’t intervened, Walt continues steadily, “I did it for me. I liked it. I was good at it. And I was really . . . I was alive.” With a look of recognition, relief, and even fulfillment, Skyler bids Walt a teary-eyed farewell.

For once, Walt has told the whole truth—to Skyler and to himself. And he will not apologize for it. He will not apologize because he stands by his life of self-direction. The “self” at stake, the “who” of Walter White, first raised in Skyler’s comical exclamation in bed, “Walter, is that you?” cannot be understood as simply an egotistical man or as an aloof manipulator of society. The “self” should be understood as a distinctive narrative, but one from which we can draw a lesson and thereby participate: Walter White, the man who reclaimed his life in the face of “sublime calamity,” who at first rejected his oppressive society with an angry “no!” but who then transformed the sources of his despair into roles and relationships he could affirm. Walter White: the man who brought destruction upon the lives of many—including the very people he sought to protect—but who ultimately did so with a view to the whole, and with the strength to bear the guilt of his deed. Walter White, a tightrope “between beast and overman,”12 a model of the aspiration, danger, duplicity, and honesty of human existence.

This article originally appeared in American Affairs Volume II, Number 3 (Fall 2018): 188–209.

Notes

1 Friedrich Nietzsche,

Thus Spoke Zarathustra, “Zarathustra’s Prologue,” pt. 1, in

The Portable Nietzsche, trans. Walter Kaufmann (London: Chatto and Windus, 1971), 129–30.

2 Nietzsche, 127.

3 Nietzsche, Zarathustra, “On Redemption,” pt. 2 in The Portable Nietzsche, 251.

4 Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, “Skirmishes of an Untimely Man,” in The Portable Nietzsche, 555–56.

5 Nietzsche, Zarathustra, pt. 2, “The Stillest Hour,” in The Portable Nietzsche, 258.

6 “Not by wrath does one kill but by laughter” (Zarathustra, pt. 1, “On Reading and Writing,” in The Portable Nietzsche, 151).

7 Nietzsche, Zarathustra, pt. 2, “On the Tarantulas,” in The Portable Nietzsche, 212.

8 Nietzsche, Zarathustra, pt. 1, “On the Three Metamorphoses,” in The Portable Nietzsche, 138–39.

9 Nietzsche, “Zarathustra’s Prologue,” 129.

10 Nietzsche, Genealogy of Morals, Third Essay, section 28, in The Basic Writings of Nietzsche, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Modern Library, 2000), 599.

11 Nietzsche, Zarathustra, pt. 2, “On Self-Overcoming,” in The Portable Nietzsche, 227.

12 Nietzsche, Zarathustra, pt. 1, “Zarathustra’s Prologue,” in The Portable Nietzsche, 126.