Revitalizing the Rust Belt

Large swaths of Pennsylvania, New York, and the Midwest have stagnated for decades, resulting in unrecovered job losses nearing 60 percent in some parts of the region since the 1950s. Meanwhile, the languishing U.S. Rust Belt serves as an instrument of blame in a divisive political climate. While solutions remain elusive, the region continues to miss out on the lion’s share of the country’s vast capital resources, with over 80 percent of venture capital funding going to California, Massachusetts, and New York, and most foreign direct investment concentrated on the coasts.

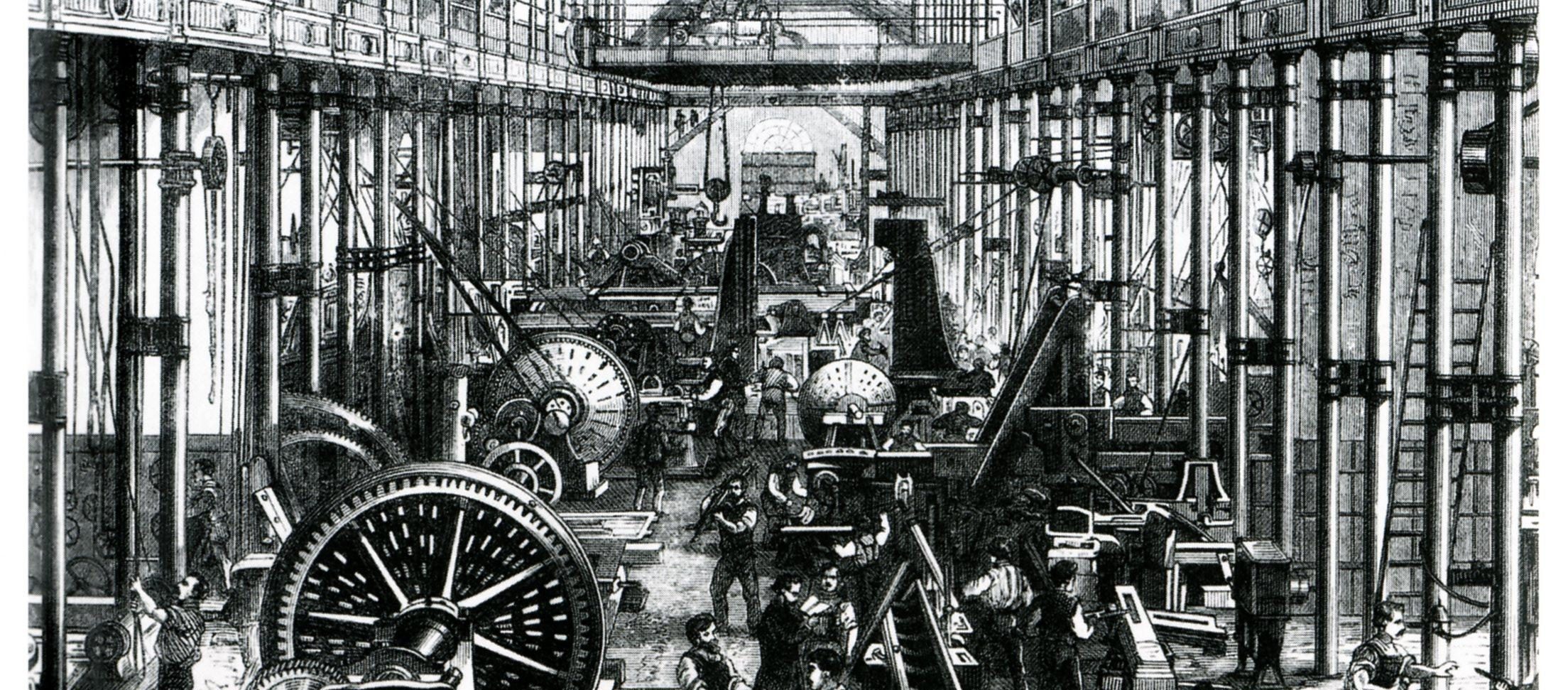

The United States experienced great shifts that gave rise to the Rust Belt. The migration of manufacturing to the South or offshore, automation, and increased competition caused large declines in output and employment. The country never addressed these issues on a national level, instead allowing the rise of one region to offset the fall of another. Contributing to this trajectory were cities that grew up around single firms (like steel in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania), often shielding dominant producers from the need to remain competitive and innovative. When those firms faltered, their locales were left with outmoded assets, environmental issues, and legacy pension liabilities, while the country’s economic dynamism refocused elsewhere.

Far from being uniform, regional centers like Columbus, Indianapolis, Minneapolis, Milwaukee, and Pittsburgh have always been more economically diversified with finance, retail, and thriving academic centers. Other cities such as Dayton, Ohio, and Gary, Indiana, struggle with economic devastation, population loss, and declining educational attainment. Solutions such as casinos, convention centers, and water parks have been offered in an attempt to attract the creative class through urban renewal. Others have contemplated bringing back industry by using the region’s energy boom, skilled labor pool, and university backbone. The solution likely involves all of the above, but so far we have refused to embrace a sufficiently comprehensive strategy.

Ideological commitments of both the Right and the Left have prevented the implementation of the sort of development efforts necessary to revive distressed regions. But if we were to attempt a bolder and more holistic approach to reviving these regions and helping some of their struggling factory towns—without relying solely on public finance—what would it look like?

From Despair to Dynamo in Industrial Silesia

America is not the first country to find itself at this point on the industrial curve. The most common examples of similar challenges are the United Kingdom and Germany. But another example, central Europe, is overlooked. Central Europe found itself in free fall in the 1990s when the Soviet Union abruptly ended. Without the consumer capacity available in rich Western countries, its heavily industrialized regions could not rely on greener domestic pastures to lift the country up. Central Europeans had to address their rust belt head-on, and without relying on massive treasury support. The region would eventually pull itself up by the bootstraps to become economically viable, thanks in large part to the adoption of bold policy ideas.

Central Europe was in a worse position in the 1990s than the American Rust Belt ever was. When the Iron Curtain fell, the new leadership had to address economic decline with national and sectoral policies designed to prevent chronic decline and maintain work force levels competitive with their neighbors in the European Union. They had to restructure their economies sustainably, rationalize their industrial sectors, and lower tariff barriers. Steel was one of the toughest sectors to be tackled.

Steel, textiles, and heavy industry had been high-profile sectors under central planning. The steel sector, in particular, benefited from large, long-term subsidies and centrally planned demand, with a few plants producing most of the output and absorbing a skewed share of capital, skilled labor, and energy. In Poland, for instance, only two plants had been built between 1945 and 1982, and the largest one—Nowa Huta—was built in the mid-1950s. By the end of the socialist era, most of the prewar steel plants were plagued by low productivity, low-quality metal, and high pollution.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the industrial heartland of Silesia, a large coal basin bordering Germany, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, suffered an economic crisis. Recession, followed by post-socialist reform, all hammered manufacturing output. With the onset of rapid economic transformation and reorientation toward the EU, subsidies dried up, the steel sector was opened to competition, and import tariffs on steel fell from 9 to 3 percent. Some manufacturing facilities could support an expansion of production, but others required modernization. Some facilities offered no future prospects and were shuttered, leaving economic and environmental devastation and massive social dislocation.

One of the most degraded areas was Katowice. In its heyday, Katowice Steel employed more than twenty thousand people and produced nearly five million tons of steel per year. When the Communist regime collapsed, the outmoded, environmentally noxious Katowice Steel required profound environmental remediation and upgrading. The company lost its eastern markets, production dwindled, large strikes ensued, and the plant considered declaring bankruptcy. Policymakers overseeing the Silesia region boldly introduced economic transformation, retraining, and reorientation. They explained to voters that transformation would be painful in the short term but was the only pathway to a sustainable economic future.

Through the ongoing reforms, Katowice Steel combined with another steel plant and, in 2005, was sold to Mittal Steel Poland. In return for access to the investment, the Polish government required Mittal to assume debt and inject fresh investment so that the plants could upgrade. With a cornerstone investment, the plants became creditworthy and gained improved access to bank financing. Today, the mill has to comply with high EU environmental standards and is bombarded with cheap eastern European and Asian imports. Yet it is a stable, although scaled-down, producer. Even more interesting is the dynamic growth in the surrounding area.

Far from the despondent situation of yore, today Katowice is considered an emerging metropolis, as the sixteenth most economically powerful metropolitan area in the EU by GDP, with $114.5 billion in output, after having seen its population shrink when the reforms first began in 1990. The area has transformed from a steel and coal mining center into one of the most attractive investment areas for modern economy sectors in central Europe. The city has one of the lowest unemployment rates in the country.

The Role of Public Policies

How did policy makers support this turnaround? In 1990, the new Polish government undertook sector studies, working with firms like Bain and McKinsey, to identify the main obstacles to growth, increase competitiveness of industrial enterprises, and prepare major restructuring programs. The main recommendations involved cost rationalization and modernization—for instance, through the computerization of manufacturing systems. Perhaps the most critical recommendation was to attract sizeable private investment by joint-venturing with Western firms. How did they attract those firms?

First and foremost, they created a robust framework for strategic investment in return for jobs, training, and respect for modern environmental norms, enticing investors through short-term tax relief, environmental and other liability burden-sharing, and the creation of special economic zones. They publicly supported investors through tax concessions for certain capital expenditures or the creation of new jobs, guided by comprehensive sector studies, detailing the existing number and size of firms, market share, customer profiles, financial health, employment, and other issues within each sector, as well as what a more rationalized and optimized sector would look like in terms of these metrics. These comprehensive policies resulted in large capital inflows, such as corporate investments by General Motors in Gliwice and Fiat in Bielsko-Biala, which enabled the region to transform.

Policy makers vigorously promoted opportunity, publishing guides detailing incentives and other information. At a national level, they created an “Investor Front Desk”—welcoming investors with studies, data, and lists of companies interested in partnering. In this nurturing environment, Pittsburgh Glass Works chose Poland for a new global manufacturing location based on operating costs, business conditions, and friendly government. 3M, DCT, Capgemini, Moneygram, Mercedes-Benz, and others have all done likewise. The Katowice Special Economic Zone now boasts more than 250 business entities employing nearly 65,000 staff and attracting investors from the United States, Italy, and Poland, as well as Japan and Germany, that have invested more than €6 billion.

The sector studies guided investors seeking to purchase former state assets and provided profiles of each firm. As privatization took hold, hundreds of thousands of new private businesses sprang to life in the region. Eventually, the turnaround of behemoths lagged and new businesses became the engine of growth, often on the basis of more efficient production processes for niche parts of basic heavy industry (like producing heat exchange units for the energy sector). In both cases, the private sector was reborn through comprehensive reorganization of work and skill specialization, implementation of management best practices (such as performance-based pay), identification of real demand, and financial discipline.

On the back of large private investments, manufacturing increased its share of exports, reflecting a shift from manufacturing of basic goods such as food and steel to more complex, value-added goods. Large enterprises with more than 250 employees played a vital role, receiving most of the investment into innovation in the manufacturing sector. Companies revised their product mixes, no longer selling just to other protected businesses unconcerned with cost or profit. Following through with the reforms to the end, successive national governments to this day continue pressing to complete the country’s ambitious privatization goals.

Once the most polluted and outmoded region in all of Europe, Lower Silesia has become one of the most advanced industrial regions in Poland. It grew 7.5 percent annually from 2000 to 2010, and unemployment dropped 9 percent from 2002 to 2013. The relative outperformance of the region is owing to higher labor productivity and a high concentration of investment.

Building on a supportive policy framework, the region developed its infrastructure and cultivated a scientific and technological specialization in medical and life science, chemical science, information and communication technology, mathematics, and physics. Becoming a leading manufacturer of white goods (electromechanical) as well as automotive goods, the region transformed holistically, developing large IT company groupings, a burgeoning pharmaceutical sector, and a thriving hub for business-process outsourcing and shared-service companies.

The bottom line: after painful reforms, industrial Silesia repositioned itself—through astute policy planning, high productivity, low wages, and an educated labor force—as an increasingly attractive outsourcing destination for high-tech manufacturing, shale gas production, clean energy, and financial services. The parallel is far from perfect, given the role of the European Union, but it shows what can be done.

Reasons for Optimism in the United States

America’s Rust Belt challenges arose over several years, as locales that once specialized in large-scale manufacturing of finished, medium-to-heavy industrial and consumer products and the transport of raw materials for heavy industry were hit by various forces. The region had been shielded from foreign competition during the 1970s through protection granted by Congress in response to industry lobbying efforts. As a result, many large steel and coal producers failed to innovate, rationalize, or upgrade their operations.

In the second half of the twentieth century, manufacturing began migrating to the American southeast or offshore, while automation expanded and U.S. steel and coal companies found themselves struggling to compete with producers from emerging markets with cheaper labor costs. Some of these former heavy industrial areas have recovered by shifting to tech or services, but many have not fared well. As these regions languished, other areas of the country flourished, such as the southeast (in manufacturing) and the northwest, with the rise of Silicon Valley.

Youngstown, Ohio, experienced a different trajectory than Katowice. Between the 1920s and 1960s, the city was an industrial steel hub that never diversified its economy. Economic changes in the 1970s—recession in the global steel market, the 1973 oil crisis, and the opening of trade with China—led to the “steel crisis,” forcing many plants to close. Youngstown was hit hard, with the abrupt closure of debt-laden Youngstown steelmaker Sheet and Tube on September 19, 1977, referred to as “Black Monday,” eliminating five thousand jobs. The area received little investment and failed to revive in the years afterward.

Without a comprehensive policy overlay, vast regions of the industrial heartland suffered. Far from being a deliberate choice, this dearth of policy support reflected a late twentieth-century tendency to limit U.S. economic policy to federal taxation, government budgets, trade agreements, the money supply, and interest rates, as well as interventions in the labor market (minimum wage and hours regulation). When a Rust Belt appears, the federal voice is absent. If the United States wanted to look more squarely at the Rust Belt while remaining true to its core economic ethos, what other bold policies might be available?

The U.S. Rust Belt is home to positive trends that a more robust policy framework could easily build on. Unlike higher-priced coastal cities, the former industrial heartland has several key inputs to industry: abundant, affordable energy and the nation’s freshwater supply (shielded from oceanic natural disasters like hurricanes), as well as human capital. On a socioeconomic level, many communities house stellar colleges and universities, producing the nation’s top engineers and scientists, and are positioned to benefit from academic symbiosis and innovation. These regions also have far more reasonably priced commercial and residential real estate than coastal urban meccas.

Some cities, such as Columbus and Raleigh, are thriving through a mix of traditional and knowledge-based industries. Akron, Ohio, has built on its heritage as a tiremaker to become a polymer hub city, with companies looking at new ways to commercialize synthetic materials, and with a Polymer Training Center housing 120 academics and 700 graduate students. Many locales are using a participatory strategy, including investment policy roles at all levels of government that feed into each other, with a broad strategy at the top. This model should be emulated widely.

How do you get large, deep-pocketed strategic and financial players to invest in the transformation of former industrial centers—for instance, in the burgeoning hardware renaissance (boosted by 3-D printing and ample broadband)? Here the lessons of central Europe apply. Former industrial centers have cheap property—shuttered mills and warehouses where younger entrepreneurs can hatch businesses without allocating more of their precious funding to overhead. Add to that the Midwest’s advantage over European and Asian rivals in cheaper energy locally, and the opportunity is alluring.

A wealth of human capital already exists in the region. While it has lost population overall, more educated workers move from New York City and Brooklyn to rising counties in the Rust Belt than the reverse. The Midwest has great educational and medical facilities. Indeed, the region has seen a revival of job growth in energy, manufacturing, and logistics, followed by construction in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Illinois, and Indiana. The modern backdrop is already in place, moving the region far beyond the central European comparison. Finally, the United States is home to the world’s wealthiest institutional investors, whereas central Europe had to rely solely on foreign investment.

A Roadmap for Economic Revival

As part of a comprehensive approach, U.S. policymakers should consider some of the bolder ideas from Central Europe:

Develop an aspirational sector plan. Have a sector plan at the ready that embraces a vision for what the area’s industrial layout might look like for a particular state or locale. Detroit, for instance, is an ideal site for electric car production and related industries, such as advanced batteries and recharging technology and components. The federal government could work with state and local planners to create an aspirational industrial map (with a few alternative iterations) for all of Michigan and possibly the greater region, showing existing sectoral allocation and productive assets, available human resources and skill-set profile, and adjacent resources such as power, water, transportation infrastructure, backbone ICT, and academic facilities.

Legislate for investment. Offer tax holidays or rate reductions in return for not just investment but fulfillment of key needs, such as expansion capital, employment, job training, environmental liability sharing, and debt/pension liability assumption.

Invest in youth. Establish innovation hubs to diversify beyond retail and low-wage manufacturing, and encourage co-op and internship programs.

Harness academic centers for innovation in all commercial growth sectors—for example, as in the Three Rivers Venture Fair in the Pittsburgh area. These regions house Carnegie Mellon, Case Western Reserve, University of Pittsburgh, and other leading engineering universities. These institutions have sizeable resources to devote to designing programs to develop the creative and technical skills required for “new manufacturing.” Such resources should be leveraged to support robotics, next-generation technology hardware, medical innovation, national security, and advanced materials industries. This support need not occur through public funding and could be led by new manufacturing trade associations that bring industry and academia together.

Investment models. Adopt business-friendly investment codes with model documentation. In central Europe, many locales offer “investment guides” outlining the core laws and regulations in place, the types of corporate entities, tax and labor considerations (and bargaining positions for particular sectors), the steps to forming a joint venture, and model investment documentation. This serves as a roadmap not just for investors but for local business owners seeking investments to use as a preparatory tool.

Leverage national and local small business associations, as well as local service clubs, to expand financing options and track local investment opportunities. The first step an interested investor will take when approaching a new market is to assess the full set of opportunities that match specific criteria relating to revenues, market share, shareholding (whether private or public), customer profile, basic history, and year of founding. This data set is then used as the basis for the investor’s “funnel,” through which the set is pared down to the subset of target investee firms. These same data reservoirs can also publicize financing options available to local businesses.

Overcoming Political Obstacles

Despite having vast institutional wealth, a strong IT backbone, modern universities, and an experienced workforce, the United States largely avoided planning for a transitioning economy and the resulting political consequences. Indeed, in the former Communist belt, political backlash arose against such sweeping policy changes, but they persevered. Instead of continuing to talk about reviving former jobs that are lost forever, public leaders need to frame the policy choices as a worthy benefit for the overall population, prepare youth for new jobs, and do enough to support dislocated workers. Urban renewal in downtown Detroit, for instance, is a start. But reviving the economic engine of the former car city also calls for enticing large strategic investment.

The measures outlined above will likely provoke opposition from both the Left and the Right. Some on the left will object to tax incentives that have been used in the past to increase corporate profits without benefitting labor or the broader community. For these reasons, it is important to tie such incentives to larger economic goals (as discussed above), but skeptical voices need to understand that successful economic development requires private sector support and participation.

Meanwhile, market fundamentalists on the right will object to any government intervention in the economy as “inefficient.” Yet abandoning distressed areas often means the permanent destruction of human and physical capital. Failures of planning in the past can only be remedied by better planning and execution in the future, not a total abdication of political and economic responsibility. As the example of Silesia shows, industrial planning and public-private partnerships can be highly effective.

Only a vibrant policy framework will achieve lasting change in declining regions, and some elements of central Europe’s success stories can be emulated in America.