France 2017: The Impossible Conservative Revolution?

France has just emerged from one of the maddest years of politics in its democratic history. It is often said that the French adore politics; but at the time of writing, the emotion that prevails at the close of legislative elections marked by a massive and record abstention is one of disgust, felt by voters as much on the right as on the left.

Let us go back.

One year ago, in July 2016, the script of the presidential election was already written. The center-right party, Les Républicains, was bound to win the election. When, in November 2016, François Fillon was elected the Républicain candidate, it was certain that he would win the presidential election—so much so that to everyone’s surprise, François Hollande, instead of running as an incumbent president hoping for a second term, decided not even to compete. The outcome of his presidency, in the assessment of the French people, was so catastrophic that he had very little chance of success anyway. Emmanuel Macron was very low in the polls, and the French Socialist Party made the mistake of electing Benoît Hamon as its candidate during the primaries. From then on, it seemed certain that we would have a second-round election between François Fillon and Marine Le Pen.

Marine Le Pen: a year ago, she was projected to be in the lead in the first round of the presidential election, and consistently polled at 30 percent of the vote for practically all of 2016. The scenario that had already almost happened in Austria, with the quasi-election of Norbert Hofer, had left the Front National’s opponents fearing the worst. It was thought in France and elsewhere that Brexit and Trump would be followed by the election of Marine Le Pen. What if, they wondered, Marine Le Pen succeeded in the second round by “exploiting” the terrible attacks that have struck France during the last two years—first Charlie Hebdo, then the Bataclan and the Parisian cafés, and the Nice attack? What if she took advantage of the barely contained migration crisis of Fall 2016, as well as the growing suspicion between different religious communities in France? A year ago even François Hollande, in a livre de confidences to journalists that caused quite a sensation, believed that Marine Le Pen was going to win. And if she did not win, the expectation was at least for a staggering advance in the legislative elections for a group of Front National deputies. Who knows? We were perhaps going to have an ungovernable Assembly, divided among the Socialistes, Républicains, and Frontists—maybe even a crisis of regime and the end of the Fifth Republic.

Let us go back a little further: 2017 was also expected to reveal the strength of new political movements of the conservative Right. In 2013, an immense popular movement rose up against gay marriage in France, and had pushed a new generation of young people to enter politics. Some had chosen the Républicains through the political movement Sens Commun, a kind of Tea Party à la française, which had first secured the support of Nicolas Sarkozy before being very skillfully recovered by François Fillon. Others had chosen the Front National, where, behind Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, they hoped to embody a solid and enlightened Right, capable of alliances with the Républicains. This whole conservative movement wanted to reaffirm the primacy of politics over economics, and reaffirm the importance of social conservatism in the definition of the Right. They did so with some success. Considerable sales of the books of Eric Zemmour and Philippe de Villiers also indicated that the electorate on the right had a profound dynamic in its favor.

One year later: none of that happened. Marine Le Pen almost failed to make the second round and was nearly overtaken in the first round by François Fillon, the Républicain candidate who was destroyed by the media’s revelations of legal accusations against him. Emmanuel Macron thus took the lead from the first round, in an ideal scenario face-to-face with Marine Le Pen, who was still tarnished with her father’s anti-Semitism. Macron, after striking her down in perhaps one of the most influential presidential debates in the history of the major Western democracies, was elected president of the French Republic. At age 39, he is one of the youngest leaders in the world, though he did not even have a party one year prior. In the legislative elections, his new party, La République en Marche (LREM) amassed one of the greatest majorities of the Fifth Republic, while the Socialist Party seems to have disappeared. The Front National, with only eight deputies, cannot even form a distinct parliamentary group—the sine qua non of influence in legislative debates. Meanwhile, the entire so-called conservative movement, having entertained the wildest hopes for 2017, has been crushed. Now relegated to the background, it is accused by some of being responsible for the defeat of François Fillon. And in any case, it has been destroyed by the brilliant victory of Emmanuel Macron’s deputies and destabilized by the surprise retreat of Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, who was the strongest link between Républicains and the Front National.

Instead of the anticipated conservative revolution, France has experienced a centrist revolution under the leadership of the formidable tactician and strategist Emmanuel Macron and his La République en Marche. In a France that wants to become ever more American, why did France remain immune to political events such as Brexit and the election of Trump? More pointedly: how has Macron become the French Trump? How did he succeed by marvelously exploiting the position of the outsider? Like Trump, he was in his way a man of the system who became an “outsider,” capable of rendering all the established political forces obsolete. The difference, of course, is that Macron is a candidate of a new centrist party, while Trump took over an existing right-wing party.

To understand what happened, we will review a few of the more salient points of the campaign, and then examine how the triumph of Emmanuel Macron—pompously described by the French press as “Jupiter”—sends contradictory signals of strengths and weaknesses. His first weeks in power prompt one to imagine very different scenarios, oscillating between dazzling success and major political crisis.

American-Style Primaries Do Not Work in France

The American primary system was the first cause of all the political upheavals experienced this year. In failing to understand that the primary system of the United States presupposes the existence of only two parties, the strategists of the major parties previously in power in France—the Socialist Party and the Républicains—have profoundly destabilized their electoral bases. For decades these two parties have indeed been the moderate and balanced expression of more radical alternatives. Unlike in the United States, however, in France more extreme positions are not put forward within the two major parties but outside them. These alternatives include parties such as that of Jean-Luc Mélenchon, heir to the French Communist tradition as head of La France Insoumise, or that of Marine Le Pen, heiress to the leadership of the Front National, bequeathed to her by her father.

Although the most extreme opinions are not part of the platforms of the Socialist Party or the Républicains, the use of American-style primaries has upset the entire electoral balance laboriously maintained over the decades. Thus Benoît Hamon, the candidate elected in the Socialist primary, was seen as an extremist candidate capable of flirting with the far Left, and François Fillon, the candidate elected in the Républicain primary, was seen as an extreme conservative flirting with Sens Commun. In any case, whether it was really true or not, the candidates elected in the two primaries appeared to hold polarized political positions. From the outset, then, they put themselves in the dangerous position of destroying their support within the center-left and the center-right, which has long been the basis of reelection for the Socialists and Républicains. In these circumstances, far from renewing their respective parties by finally assuming a clear political dividing line, they gave the impression (with a blatant lack of sincerity) of chasing after the supporters of strong-willed orators like Jean-Luc Mélenchon or Marine Le Pen. From the start, Hamon and Fillon lost the novelty premium and instead appeared as calculating—all while pushing their moderate and centrist electorate toward Emmanuel Macron.

L’affaire Fillon, a First in France

Beyond the primaries, François Fillon had to face an incomparable number of scandalous revelations by the newspaper Le Canard enchaîné (typical for this newspaper). But in the precise context of the presidential election, these revelations put an end to a tacit French tradition in which such attacks are suspended during a campaign of this importance. Scandal used to be reserved for before or after the presidential election. In France, although it may seem wrong from a British or American perspective, presidential candidates are believed to deserve the opportunity to fight their electoral battle without such allegations, simply for having achieved the status of candidate. Thus for the first time in France—although everybody intuits for themselves that all French politicians are reproachable for something or other—the attacks were all concentrated, in the middle of a campaign and with a violence never before seen in our political culture, exclusively on François Fillon, mostly regarding the fraudulent employment of his wife as a parliamentary assistant.

Fillon, however, showed the utmost imprudence in not examining his weaknesses before entering the campaign; in underestimating the importance of the attack; and in his stunning lack of responsiveness from the beginning. Fillon also failed to make a counterattack, as Trump might have, turning this weakness into a counteroffensive emblematic of the new politics and the new message he wished to embody.

In fact, his whole program was accused of being a passive copy of Thatcherism or Reaganism. This is not wrong. Fillon’s platform embraced a liberal approach to economics and a preference for conservatism and security in social issues. The problem was not necessarily this program as such, which was rather well constructed and even courageous, but Fillon’s inability to break the electorate’s perception that these reforms were obsolete measures from the past—and imported from foreign countries. He needed to give his platform a breath of the new, iconoclastic politics, relying where necessary on the so-called conservative intellectual forces that were trying to bring together all the French people weary of political correctness and the lack of any honesty in politics. He had a window of opportunity, which he vaguely understood when he made Sens Commun his principal support at the time of the primaries. But as soon as the primary was won, his obsession was to court the center-right and official respectability, without understanding that, with nothing to lose under the weight of legal accusations, it was necessary to risk transgression.

A Calamitous Campaign for Marine Le Pen

Disastrous primaries for the major parties, the accusations against Fillon—these still do not suffice to explain why the year unfolded as it did. For the great novelty of this election, predicted for months, was supposed to be the breakthrough of the Front National, if not to the presidency then at least to victories in the legislative elections.

But there too, nothing happened as expected.

I agree with those who have pointed to how poorly Marine Le Pen ran her campaign. All the fundamental parts of her political movement were burning issues: the migration crisis experienced by the European Union for two years, painfully and temporarily resolved by walls on the borders of Hungary and Austria and by dubious agreements with Turkey; so too the bloody attacks in France in November 2015 and July 2016, which gave her a window of opportunity on themes that neither Emmanuel Macron nor Benoît Hamon nor Jean-Luc Mélenchon wanted to touch. From the moment François Fillon became compromised by his scandals, Marine Le Pen could have been the only person speaking forcefully about security and French identity, which the polls have shown for several years uniting the supporters of the Républicains and the Front National.

Instead of this, she preferred to focus on leaving the European Union and the eurozone—certainly a fascinating and important subject, but outside of the intellectual scope of the current structure of the Front National and, as evidenced by her performance in the second-round presidential debate, beyond her own capabilities. In her debate against Emmanuel Macron, a former banker and economy minister, she was out of her league. He did not hesitate to point this out to her. Met with her persistence in trying to explain to him how easy it was to withdraw from the euro, he left her to drown in front of appalled viewers.

By choosing to make the question of French sovereignty the heart of her political platform, with the sole aim of rallying sovereigntists on the left as much as on the right, she made the mistake of confusing a referendum campaign such as Brexit with a presidential campaign, which by contrast always plays on domestic issues. For better or worse, European affairs, in the mind of the average voter, belong to the complicated realm of international politics.

The question of remaining in or leaving the European Union is a major question for every European nation today. But it has no place in a presidential campaign, much less when it is brought forward by candidates who are perceived, rightly or wrongly, as radicalized or unreflective. It induces too much anxiety and becomes too complicated to be treated in this way.

At the heart of Marine Le Pen’s major strategic error lies the question of the euro, which dramatically distinguishes France from the United Kingdom when it comes to the issue of leaving the European Union. For the United Kingdom, which is neither in the Schengen Area nor the eurozone, leaving the European Union is far easier than it would be for France, which would have to leave both.

Between the two rounds of the election, certain statements from the Front National, coupled with the rallying of the Gaullist parliamentarian Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, created the illusion that Marine Le Pen was ready to backpedal on leaving the euro in favor of a complex monetary system of two currencies. It was too late. On a subject brandished by the Front National for years, it seemed incomprehensible that a candidate with such uncompromising political positions as Marine Le Pen would be so unprepared to explain how she could manage such a delicate transition.

Macron, Year Zero: An Energetic and Uncompromising Exercise of Power

The indisputably talented Emmanuel Macron has decided to exercise all the power that fell to him and not to allow any rivalry. Elected president thanks to a frenzied election that killed the Socialist Party, tore the Républicains apart, and cut off the advance of the Front National entirely, he has at his disposal one of the largest majorities ever achieved in the National Assembly. A real political revolution, but not the one expected—on the contrary, a centrist revolution. And now, with the defeat of the Right in the legislative elections, a new situation is coming into view.

First Macron has obtained the admiration or the stupefaction of the French people who, respectively, supported or opposed him. Macron is very far from the image of weakness that we still have in France of start-ups and upstarts—of which Macron claims to be the political version. The signals sent by his political maneuvers attest to a very agile, cynical mind set on exercising all the power that he has in his hands, in a very presidential and vertical interpretation of power.

The way in which he orchestrated his political alliances is frighteningly Machiavellian. Macron, for example, owes his election to François Bayrou, a veteran of French politics who desperately clung to a strong centrism throughout his career. Before Bayrou gave his support to Macron in February, Macron never exceeded 9 percent in the polls. Thanks to his reputation as a wise old man, François Bayrou allowed Macron to leap up in the polls and finally to take off. Yet as soon as the presidential election ended, and despite giving some thanks to Bayrou’s party via concessions of constituencies for the legislative campaigns, Macron let a case of fraudulent jobs emerge about François Bayrou’s party, Le Mouvement démocrate (any similarity to the Fillon affair is surely fortuitous). Bayrou had just been appointed justice minister, and two of his closest lieutenants had become defense minister and minister of European affairs. But the entire Bayrou faction in the government had to resign following the revelations of this affair. In this way, at the beginning of his term, Emmanuel Macron rid himself of the only person capable of standing up to him inside the government.

Consider a second example: Nathalie Kosciuzko-Morizet, a former minister under Nicolas Sarkozy and a well-known political figure in France. Although in the Républicain party, she has long been thought of as a centrist and could very well have been lured away by Emmanuel Macron to join his government. After all, he lured away other Républicain deputies in order to make their party implode. In any case, according to public opinion, she and he were completely compatible and could work together. But Kosciuzko-Morizet is also the leader of the opposition in the municipal Council of Paris. He let her be beaten in the legislative elections by one of the candidates of his party, while other candidates on the right had been entitled, because of their political “compatibility,” to special treatment—not having opponents from the president’s party. His tactic sent a very clear signal that he would not waste time with parliamentary allies of independent political movements or ideas. He needed servile allies.

Moreover, for the first time in the National Assembly, certain key posts in parliamentary commissions traditionally reserved for the opposition have been awarded to supporters of the presidential majority. Macron has in fact left no important role in the National Assembly to the opposition.

Weak Political Legitimacy

Despite Macron’s strength, the basis of “Macronism” itself still remains very weak. The exercise of power is shared between a government of technocrats who are ultracompetent in their fields, and a National Assembly of silent deputies—political novices who could potentially prove to be blunderers or uncontrollable in the event of major political or social tensions. Some of these deputies gave embarrassing interviews during the legislative campaign. Emmanuel Macron may be adroit, but his supporters in the legislature may not be, at least not always.

The main problem lies in the overall question of Macron’s legitimacy. Without trying to minimize the victory of Emmanuel Macron, we must note that, apart from the 24 percent of voters who voted for him in the first round of the presidential election, and an equivalent proportion of the French who voted for his new party in the legislative elections, 75 percent of France may not support his policies—an unprecedented situation. And French voters for the most part showed no interest in the legislative elections. Based on this, as soon as the first serious problems arise, how will the French people react?

Macron’s administration poses a similar problem: it is composed of counselors or senior officials who are individually remarkable or technically competent, but who have very weak electoral legitimacy in national politics. Some of these already suffered prior political rebukes. Bruno Lemaire, the economy and finance minister, ran in the Républicain primary last November and won a mere 2.4 percent of the vote! Yet Macron has placed him at the head of the French economy—with what other legitimacy than the merely technical competence of a senior functionary? If Macron undertakes wide-ranging reforms in France, the weakness of his government’s merely technocratic legitimacy could return.

France’s structural tensions have existed for a long time, and explain the rise of the Front National on the one hand and that of the leftist party, La France insoumise, on the other. Between the two, and by means of their candidates, these parties gathered 40 percent of the vote in the first round of the presidential election—a vast amount. And in the second round of the presidential election, Marine Le Pen gathered 11 million votes all the same, setting an absolute record for the Front National. These opponents have everything to fear from Emmanuel Macron, who will be stronger and more determined than anyone could have imagined, and presumably everything to gain by opposing him. In short, Emmanuel Macron faces a problem of legitimacy which he no doubt underestimates. Intoxicated by what he has accomplished, he has not measured the fragility of his position from a democratic point of view.

The Probability of a Major Sociopolitical Crisis

Under these circumstances, the sociopolitical crisis that looms as a result of the proposed reforms to the labor code could resonate widely. The proposed reforms will use “ordinances,” a mechanism through which the government is given authorization from Parliament to legislate without parliamentary debate. The issue at heart will not even be determining whether the labor law needs to be reformed or not, but whether Emmanuel Macron really has the legitimacy to do it. If street-level opposition were to crystallize different factions of the opposition frustrated by the unexpected results of the elections, and to shift the debate from the basic question posed by the labor law reform to the question of Macron’s real political legitimacy, the crisis could be considerable. If Macron’s major project of reform were to fail, the crisis could validate the real political weakness of a president unexpectedly elected.

Admittedly, France needs flexibility in labor organization as well as its job market. Bureaucracy and rigidity have little by little stifled the flexibility that is indispensable for acting and reacting in a changing environment. But the French tradition of economic development is based, whether we like it or not, on a strategic state which steers the market economy and in which liberalism remains controlled. It is in this way that General de Gaulle reformed the country in the 1960s. Thus, the reproach made against François Fillon’s program could just as well have been applied to Emmanuel Macron’s project: in both cases, their liberalism did not and does not say how it intends to acclimate itself to the French tradition, and to respect voters’ wishes that changes to the flexibility of labor are made only on the condition that someone tells them how the French state will continue to play its historical role in the economy.

From there, two scenarios emerge for Emmanuel Macron.

In the first, he may fail for lack of political legitimacy, for lack of reforming through normal parliamentary procedure, or else as a result of the errors of the political novices who surround him (as well as for lack of humility in the exercise of power). In this case, the repudiation of him could be as biting as his accession to power was rapid. Many people have reason to take revenge: disillusioned journalists, the parliamentary deputies on the right and the left, the opposition parties in Parliament who are enraged that they have no political leverage, the so-called extreme parties (Front National or La France Insoumise), the trade unions—and the people themselves.

There remain the problems that Emmanuel Macron’s party hardly addresses: security, the anti-terrorist struggle, increased social tensions, profound divisions between rich cities and rural areas disconnected from the benefits of globalization. If Emmanuel Macron were to fail in his heralded and dramatized reform of the labor law, this sign of weakness could be a prelude to a political stampede.

Second scenario: Macron takes advantage of the bewilderment caused by his accession to power and, maintaining his iron grip on the country and its institutions (and resisting the injunctions of the unions), he forces his measures through without Parliament. He would then become the only president in decades to have succeeded in fundamentally modifying the conditions of employment in France in a way favorable to enterprise. If he were to succeed in this way, he would perfectly fulfill the objectives of a certain rightist economic position, one held by a kind of upper class which is wealthy or at least little affected by economic crises or transformations. In this case, it will be very difficult for the right-wing opposition, whether they are still in Les Républicains or in the Front National, to restructure itself.

Given his age, Emmanuel Macron could find himself, following such a success, dominating the French political landscape for several terms. He probably aspires to do this in the manner of an Angela Merkel in Germany, as the founder of a grand coalition. In this case, he would ensure that any possibility of building a conservative opposition would dry up for a long time, and he would be able to roll out a program of the federalization of France into the European Union, which is dear to him.

The Future of the French Right

Facing Emmanuel Macron today are two forces of opposition. One, symbolically very strong in the French mentality, is embodied by Jean-Luc Mélenchon—the voice of the authentic French socialist and Communist tradition, which will find expression in the social conflict which looms around the reform of the labor law. The other, scattered but numerous in its number of deputies, is the Right, trying to find its footing after the defeat of the Républicains as well as the Front National.

The first, thanks to a successful power struggle, and profiting from all the weaknesses we identified in the power structure set up by Emmanuel Macron, could manage to restore the Left. The French remain more attached to protection than to the creation of wealth, and remain attached to their famous regime of social entitlements built up over decades.

The Right, meanwhile, gave every indication of a deep crisis of conviction over the course of this election. The Républicains did not know how to stand together with their candidate, François Fillon. As for the Front National, it has been profoundly destabilized by Marine Le Pen’s personal strategic choices and those of her main advisor, Florian Philippot, who put European questions ahead of her regular program centered on security and immigration.

The Questionable Legitimacy of Marine Le Pen

Marine Le Pen’s historic failure in the debate in the second round of the presidential election was watched by 16.5 million Frenchmen. For a long time, Marine Le Pen had complained of being caricatured or demonized by the French media, whether on the left or center, which saw in her every expression the premises of a return to the Vichy regime. But the failure of the debate was considerable precisely because few of those 16.5 million French viewers had previously seen or heard Marine Le Pen express herself without the filter of the media.

Given this opportunity, she corresponded exactly to the caricature outlined by the press: incompetent and irresponsible in her proposals on the topic of the euro; inaudible or almost inaudible on security issues; unimpressive on social questions. Marine Le Pen’s debate put an end to any potential momentum, displaying a tactless oppositional posture, lack of an overarching vision, or the competence to back it up.

But in France, politicians are like cats; they have nine lives. And today, Marine Le Pen embodies the only element of stability in the political landscape of the French Right. Nothing says that she will not be able to change her strategy.

One of the political opponents of Marine Le Pen, Bruno Mégret, has said that she has no convictions. This is without doubt a fault. But it has at least one advantage, which is that her strategic error during this campaign is more an error in judgment than in conviction. She structured her campaign according to the strategy recommended by her right-hand man, Florian Philippot, that of sovereigntism against the European Union, in order to rally the voters on the right as on the left. But adopting this strategy does not mean that she is definitively wedded to it—as evidenced by her current wish to revisit the political position of her party on the euro. Marine Le Pen is much more pragmatic and opportunistic than her political opponents lead us to believe. Unlike her father, she wants to exercise power one day. But she will have to change on these points rather quickly—or else her future in politics is nonexistent.

Emmanuel Macron and the Unification of the Right

More worrisome is another error of judgment: the refusal of the French Right to seek an alliance between the bourgeoisie and working people, an alliance without which the hoped-for political change in the manner of Brexit or Trump is impossible. This refusal is what blocks any unity in the political struggle of conservative and right-wing factions.

Every successful change in political paradigms requires both elite and popular support. Marine Le Pen’s obsession with achieving victory without alliances has compromised until now the chances of any successful shift in political paradigms. Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, by contrast, embodied this possibility in the eyes of many voters because she straddled the Républicains (symbolizing the bourgeois elites) and the Front National (which draws more support from the working class). Her retreat from political life scrambles the situation.

On the other hand, the Républicains have the same problem. The party—variously called RPR, UMP or Républicains in recent times—has an obsession with never making an alliance, even locally, with the elected members of the Front National, however far they are from being the anti-Semitic caricature which they are made into by the press. This refusal poses a serious problem of political efficacy for them, too.

Yet now the Républicains are purging their members who are most tempted to rally to Emmanuel Macron’s side—and in fact all the most centrist elements of the party, which for years had exerted considerable ideological pressure in favor of an alignment with the Left. Most often, elected officials attached to a technocratic and globalized vision of France gravitate toward Macron, and those who remain know or vaguely feel that the French Right embodies and must embody, in contrast to Emmanuel Macron, a sovereign and free nation—and, for some, a certain social conservatism.

Among them, the favorite in the elections for the president of the party is Laurent Wauquiez. A young figure in the party, at the head of the second most important region in France (Lyon), he was very close to Nicolas Sarkozy and very quickly, before François Fillon, perceived the deeply conservative dynamic at work in the right-wing electorate.

Laurent Wauquiez’s greatest challenge will be to get his party out of the ideological impasse that Alain Juppé wanted when he created the UMP, the party supporting Jacques Chirac. He will need to master an electoral platform unifying the Right and the center in a common program, which would merit in the English-speaking press the title of party of the center-right instead of party of the French Right. Once elected the head of the Républicain party, Laurent Wauquiez has a chance to end this electoral alliance which lacks ideological foundation other than an economic vision of politics that is a little more liberal than the Left. If he understands that Emmanuel Macron offers him a chance to give the Républicains a right-wing dimension, then perhaps he will overtake Marine Le Pen, perhaps he will be the artisan of a political reconstruction of the French conservative Right. If not, he will follow the course of Marine Le Pen and merely arbitrate internal ideological contradictions. For Laurent Wauquiez, the unsolvable equation will be reconciling the old right-wing technocrats with the conservatives of the new generation. For Marine Le Pen, the unsolvable equation will be reconciling patriots of the Left, attached to untenable political promises regarding social security, with patriots of the Right, above all concerned about France’s cultural identity.

Conclusion

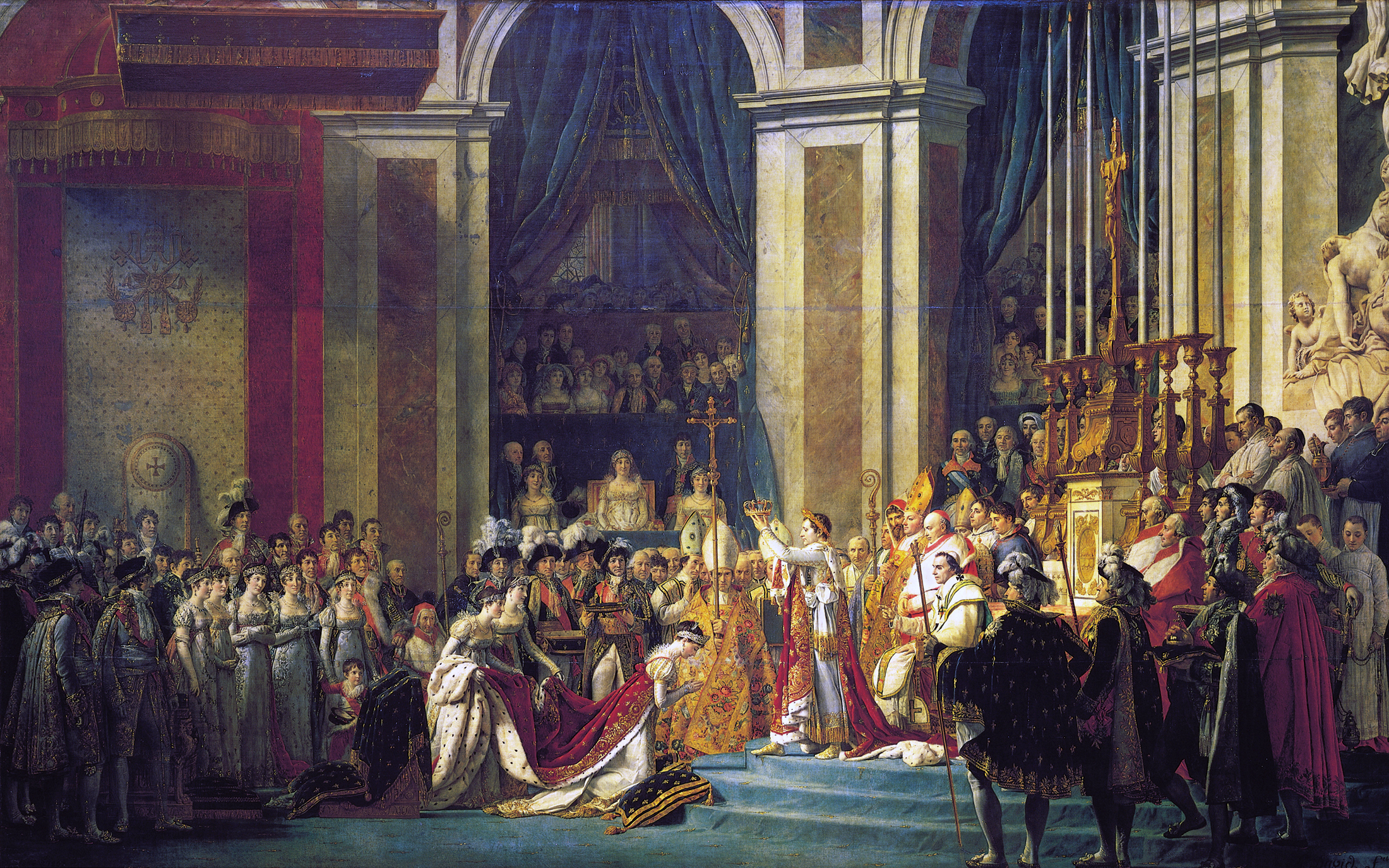

Napoléon once said, “The word impossible is not French.” This year proved that. To outside observers, French politics had an element of madness.

Macron is a shrewd and skillful maneuverer, but has only silent and inexperienced political supporters. He will be pitiless in the exercise of power. He has energy and intelligence. France is perhaps only at the beginning of a long reign à la Merkel.

But in France, “never say never.” For here, politics endures, with all due respect to the centrist revolution of Emmanuel Macron. Marine Le Pen has not said her last word, nor have the Républicains. They have at least a chance to resolve the major problem of the Right—its historical dispersal across a number of parties, beginning with the Républicains and the Front National, each with its exaggerated special features. Facing Emmanuel Macron, the obvious thing would be to ally themselves with each other, at least locally, in order to break up the ideological domination of leftist thought recycled in Emmanuel Macron’s party. But nothing is less certain, and it often seems to us, as we say, that we have the most foolish Right in the world.

What is certain is that what happens in France will not be without impact on the rest of Europe. The temporary end to the cycle of Brexit or the election of Trump is an event in itself. But its extremely precarious political situation could revive the potential for drastic change more quickly than imagined. It is certain that if so many idolize the young and brilliant French president, his potential political failures could interest more than a few, their impact on Europe would be considerable. And Emmanuel Macron is still far from having accomplished everything. To the French Right that opposes him, the time has arrived for a true unification of convictions and turning the complicated current situation into an opportunity for a solid and determined resurgence.