Capitalism without Capitalists

Western capitalism is in bad shape. A decade has passed since banks and financial houses began to crumble and took Western economies to the brink of collapse, but economic growth on both sides of the Atlantic remains weak. It is still determined more by governments and central banks than the animal spirits of entrepreneurial capitalism. It is hardly a consolation that the U.S. economy performed somewhat better than Europe’s when investment as well as new firm creation is muted, real employment levels remain low, and people feel that their economic prospects have improved little. The past ten years have been a lost decade and, unfortunately, many people in the West do not believe the next one will be much better.

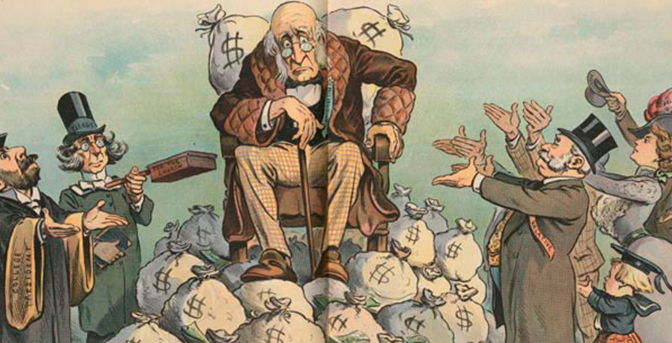

Capitalism cannot be blamed for all these problems, but it does not require much imagination, or belief in the Marxist school of history, to see how economic developments before and after the crisis that started in 2007 have fed political revolt. In both America and Europe, people are angry about their poor income growth, and they indict the “one percent” or “the establishment” for pursuing policies that benefit the rich at the expense of the middle class. They feel that the age of cost-cutting McKinsey consultants, cheap capital, and Wall Street financial engineers brought prosperity to the professional classes, but that, as a result, everyone else’s expectations were revised permanently downward. The revolt comes from both the Left and the Right, but the underlying premise is shared: capitalism hasn’t been working for me!

The economics of current political anger clearly connects with the way capitalism has evolved over the past fifty years. Capitalism has gradually been losing its dynamism and has become detached from the spirit of creative destruction that impressed such different economic thinkers as Karl Marx and Joseph Schumpeter. While there is always a cycle of ups and downs for individual sectors or the economy as a whole, the trend has been one of falling productivity growth and corporations that are less patient in how they plan or strategize to make money. Western economies have been gradually losing their ability to grow productivity and expand prosperity by smarter combinations of labor, capital, and technology. There was a productivity spurt in the late 1990s and early 2000s—mostly because of higher capital expenditures in information and communication technology, leading to more technology adaptation. But it did not last for long, and never changed the trend of declining growth. Despite the much-discussed revolution in robotics, big data, machine intelligence, and more, the Western capacity for innovation-led productivity growth has continued to fall—and has recently been close to zero.

That is not surprising for those who have followed the balance sheets of corporate America and Europe. For a long time, businesses have gradually invested less of their revenues. Their total investment represents a smaller share of gross domestic product today than in previous decades. Real expenditures on research and development (R&D) in corporate America have been on a downward trend since the 1960s, with Europe on a similar course. If businesses were preparing for a new innovation boom, the share of revenues that is spent on R&D would have gone up, but it has not. While there has been a lot of capital available for managers who seek to make their way in the world by buying other firms and consolidating markets, there has been much less of a readiness to plow money into competitive strategies based on radical innovation.

Corporations borrow more money today than ever before because the cost of capital has been relatively low for a long time. But there is nothing to suggest that all the new balance sheet capital has been used to expand productive assets or improve capacity for long-term value generation. America’s corporate sector has rather been a net contributor of capital to the rest of the economy for more than a decade. In the 1970s and 1980s, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the U.S. business sector was borrowing around 15–20 percent of the value of its productive assets. When the financial crisis hit in 2007, that had already changed: the business sector was lending 5 percent of the value of its productive assets to the rest of the economy.

Firms, therefore, have not just borrowed more—they have also saved more. Balance sheets have been propped up by soaring liquid assets: between 1979 and 2011 the ratio of cash to total assets went up from 9 to 21 percent. In the past decade that cash has been needed to keep up the valuation of firms. Under pressure from investors, companies have handed back money to shareholders at a rate that is disproportionate to their revenue and income growth. Dividends and share buybacks have repeatedly hit all-time highs, and in 2013 the Economist calculated that “38% of firms paid more in buy-backs than their cashflows could support, an unsustainable position.” With all that circulation of credit and cash, large nonfinancial enterprises have increasingly come to operate as savings institutions that make money by simply lending their capital at rates that are higher than the cost of the capital they borrow.

We do not have to go much further in order to understand the economics of political anger. This is what it is all about. Western “money-manager capitalism,” to use a term coined by the late Hyman Minsky, has changed the patterns of incentives and rewards in the economy, leading to stagnation in productivity and wages by reducing the capital investment that supports their growth. This capitalism has unfairly skewed the rewards to investors versus labor because, with corporate capital allowed to be idle, money has flowed to those seeking rents and skimming the cream off the money-circulation machine—and not to the entrepreneurs, to those taking risks, or to those providing better productivity. Firms are increasingly focused on safe, “risk-free” forms of profitmaking. Neither investors nor competitive markets have forced them to spend more capital and energy on long-term investment and innovation. Capitalism has become a “safe space” for firms that want to shield themselves against market disruption—an economic system characterized by competitive and innovative change that is too slow, rather than too fast, for economic opportunity to grow. While corporate leaders advertise their outsized appetite for innovation and disruption, the reality is that, for several decades, they have been protecting themselves against these forces of competition and have become complacent.

The Color of Capitalism Is Grey

If there is one character that represents the gradually shrinking dynamism of Western capitalism, it is the capitalist—or rather that character’s increasing absence. What really separates today’s Western capitalism from that of fifty years ago is the infrequent presence of real capitalists in the world of commerce. That is quite something for an economic system that, functionally, is about one thing alone: the ownership of firms.

Those running Western capitalism today are not really entrepreneurial capitalists but asset managers and financial institutions such as pension funds and sovereign wealth funds. They are third-party intermediaries, managing other people’s money, and have cut the link between ownership on the one hand and corporate control and entrepreneurship on the other. Because of their growing role, the color of capitalism has become grey. No one knows anymore who really owns firms: owners are known unknowns. In some cases, ownership by third-party intermediaries can have little effect on business decisions, but quite often it creates incentives that are in opposition to all the principles typically associated with entrepreneurial capitalism.

Take an institution like Vanguard, which last year owned close to 7 percent of the S&P 500, an index for the five hundred largest firms by market capitalization listed on the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq. It is also the single largest shareholder in General Electric. Therefore, to get an idea of how the biggest owner of General Electric wants its investee to deliver a good return to all its shareholders, it is first necessary to figure out who owns Vanguard. That, however, is easier said than done. Vanguard is not investing its own money. It just represents Vanguard’s different funds, and the company, which pioneered the market for mutual index funds, operates—like other funds—on a principle of diversified allocation of capital. Hence Vanguard does not necessarily hold stocks in General Electric because it has an idea for how to make a successful company even more successful.

Who are Vanguard’s twenty million savers that collectively are the biggest owner of GE? It is impossible to say, of course, but quite a number of them are not direct savers—they are beneficiaries of employers and others that have invested in pension plans. Even if we descended the stairs to the ground floor of savers, the group would be too large to ask what they want to do with their intermediated ownership of GE. Clearly, they are not putting their savings in Vanguard funds because they want an ownership role in GE. Nor are they expecting Vanguard to act as a controlling or entrepreneurial owner.

Yet Vanguard is not a bad asset manager. On the contrary, it is a company that has delivered good returns to its customers. But it is also an institution with such significant holdings in so many companies that it illustrates how the relationship between owners, the firms they own, and their managers has changed. Ultimately, when the identity of an owner is unknown, it is equally impossible to know what the owners want. When companies are principally owned and controlled by owners whose agendas are at best arcane, capitalism turns grey. It is not enough to know that investors simply desire good investment returns and, if the company cannot generate sufficient returns, investors will leave. While it is true that investors tend to be happy as long as companies make good money, it is not the desire to make money that determines whether an owner is successful or not. Money can be made in many different ways. For a company to thrive, owners with diverse interests have to be aligned with the success of the company. Often they clearly are not. Many investment funds, for instance, have significant ownership in competing firms. They are not investing in any one of these firms because they have an idea about how that company will beat all of its competitors; they are just spreading risk. Vanguard, of course, is not alone. The biggest shareholders of most listed companies in America and Europe are funds that invest on the basis of portfolio risk management.

The development of grey capitalism started forty years ago and has accelerated as institutions have been entrusted with a larger part of our savings. In 2013, natural persons owned only 40 percent of all issued public stock, down from 84 percent in the 1960s. And if we take all issued equity, the trend has been even more pronounced. In the 1950s only 6.1 percent of all issued equity was owned by institutions but, in 2009, institutions held more than 50 percent of all equity. The OECD estimated that, in 2013, insurance companies, pension funds, and investment funds administered $93 trillion of the world’s assets—five times the size of America’s gross domestic product.

Perhaps this rapid pace of recent decades will not persist, but there is a compelling reason to believe that Western capitalism will continue in this direction. Savings will need to increase as more people get closer to retirement—and, as they save more, they need more investment advice and more managers to oversee their savings. For that reason, the change from capitalist owners to institutional owners is logical. Nor will institutional owners’ growing role in the future be the result of irrational acts. The growth of these institutions is a direct reflection of the growing demand from savers with a desire to grow their assets but little knowledge of how to do so. Just like other sectors, the world of investment runs on the economies of scale and specialization, and rather than having laymen investing their savings, it is obviously better for them to use the service of professional asset managers.

But the shift from capitalist ownership to institutional ownership has undermined the ethos of capitalism and has created a new class of companies without entrepreneurial and controlling owners. Contrary to some expectations, that has not created new space for free-wheeling and entrepreneurial managers to act on their own judgment instead of following the instructions of owners. Rather, managers are subject to a growing number of rules and guidelines designed for and by risk-averse owners with little knowledge about their investees. These owners have no other option than to outsource ownership to corporate managers.

True, dispersed ownership is nothing new. Ownership was already spread out over many unknown investors before the growth of institutional capital and the advent of its new role as the controlling force of the corporate sector. What’s more, even past firms that had a large and known controlling owner—a capitalist—were not always under sound stewardship. In fact, many old titans held onto their firms for too long or passed ownership down to younger family members that had no entrepreneurial talent or interest in growing a business. So, beginning around fifty years ago, institutions constituted a welcome new breed of investors and introduced much-needed ownership competition. After decades of their silent takeover of the capitalist world, however, we are again at a point when ownership has become a defining concern in capitalism.

Absent owners prompt the creation of a litany of rules that sets the tone throughout the entire organization. In most cases, the code that replaces the ethos of entrepreneurial and controlling ownership is one that heralds the vices rather than the virtues of capitalism. It shields companies against exposure to the uncertainty that is inherent in entrepreneurship, investment, and innovation. It programs firms to seek the short and easy route to profits rather than the long and complicated one. In essence, it builds a corporate strategy that is desired for an investor who is not interested in (and, often, does not understand) long-term business building, and who is not planning to be a stakeholder for a long time.

Because these companies are large and dominate many markets globally, the effects of these owners are felt outside their firms and sectors. Ultimately, they impinge on the health of markets and entire economies, and they create a capitalism that is dull and hidebound. With no direct influence on operations or corporate development, institutions have put their emphasis on a few parameters that are mostly designed to restrict the choices of management. One such parameter is limiting discretion over the cash flow of firms. Businesses retain a much smaller part of their earnings today because absent owners have no effective way of controlling management and therefore cut its access to the company’s own cashbox. Retained earnings in American firms have moved from about 50–60 percent of net income in the 1960s to less than 10 percent today. All big investment decisions are therefore done in a way that relies more on the judgment of people outside the firm. Funding for investment has to be raised via external capital markets, which of course are not always capable of properly evaluating the investments that a company may need to undertake. In money-manager capitalism, key decisions about the future of a firm are routinely outsourced to people with little knowledge of the firm or its strategies to meet future competition.

The Rise of Corporate Managerialism

Capitalism is not just a functional system for the ownership of firms. It is, equally, an economic culture fostering a spirit of entrepreneurship and experimentation—and a desire to compete against others in free markets. When capitalism’s principles are upheld and its virtues embraced, businesses—whether new or old, small or large—thrive if owners and managers are “go-getters” who embrace uncertainty, challenge incumbents, and build value through Schumpeterian “creative destruction.”

With the rise of grey ownership, however, large and international enterprises are not the place to find this capitalist culture. Institutional owners, and the methods they use to control managers, have added complexity and risk aversion to the way companies make business decisions. Faceless owners and grey capitalism have added layers upon layers of intermediate ownership, often with different incentives. Ownership is thus separated from control, and corporate governance has become so complex that it would take a historian of the Byzantine Empire to make sense of it.

The spirit of entrepreneurship is being eroded inside corporations. The chief culprits here are the legions of corporate managers who run them. Corporate leaders project an image of being impatient for innovation and restless for change, but in practice, they prefer slow, managed development, which more easily allows them to meet the expectations of grey owners. In 1955, the average executive had between 4 and 7 performance imperatives, but today the average is between 25 and 40. With so many objectives, some of which are conflicting, corporate managers get trapped in performance rules and guidelines that are more about controlling development rather than accelerating it.

Executives often work very hard, but their long hours are spent increasingly on tasks detached from capitalist culture. Now, a growing amount of time is spent managing. Custodian culture spreads apace in the corporate world: managers prefer predictability before uncertainty, and everything revolves around an almost sacral belief in business planning. In fact, the amount of planning that takes place inside firms today would have made Soviet bureaucrats blush with embarrassment.

This corporate managerialism is seductive. It appeals to grey owners who prefer a style of management that reduces uncertainty and involves a plan for most possible events. It is certainly possible to sympathize with this ambition to minimize business uncertainties and to make the world more manageable. But a key asset of capitalism has always been that it encourages entrepreneurs to explore and make the most out of uncertainty. That is why corporate managerialism is alien to the culture of capitalism. Corporate managerialism breeds companies that avoid uncertainties. It incentivizes managers to focus exclusively on those business areas over which they have full knowledge and control. It is a culture that, in most circumstances, makes companies defensive against markets, competition, and innovation, and that prompts firms to approach risks in ways that do not fit with a spirit of entrepreneurship and experimentation. Corporate managerialism limits the space for eccentric ideas, let alone eccentric people. It is a control-and-monitor culture, always looking for new ways to manage the future according to a predictable plan. And under its regime, companies take machinelike approaches to every new opportunity and to their own development.

Any middle manager in large firms will know what this is about. They are overwhelmed by the methodologies of corporate managerialism, which guide their every step. They are frequently constrained by plans from above, including detailed operating procedures, contingency plans, and internal rules covering everything from how to write tenders to how to clean the toilet. While it is easy to understand the intentions—to increase predictability and avoid uncertainties—the unintended consequence is that companies become passive and squeeze out people with an entrepreneurial mindset. They stop chasing the unknown; they stop building strategies for something really new. Ultimately, what gives these firms their character are the plans, the rules, and the guidelines—not their quest for innovation or some desire to break the neck of their competitors.

Corporate bureaucratization has soared as a consequence of corporate managerialism, and its influence is pervasive throughout the corporate work environment. Take, for example, the rapidly increasing number of external and internal interactions that managers are forced to handle today. In 1970, managers received approximately one thousand external messages on average every year. Today managers receive approximately thirty thousand external messages annually—an increase of 2,900 percent. All these communications consume time and resources, and corporate managerialists have responded by creating new bureaucrats to manage the increasing workload. The consultancy firm Boston Consulting Group (BCG) has created an “index of complicatedness” for companies, and it shows that companies have increased the level of bureaucracy by approximately 7 percent annually—compounded for the last five decades. People working in big firms wrestle with internal red tape more today than ever before, but most of that time is actually wasted. According to the same consultancy, 40 percent of a manager’s time is consumed by writing reports and 60 percent is spent coordinating meetings. One of BCG’s in-house corporate philosophers, Yves Morieux, only needs three words to sum up most of that work: “waste of time.”

Moreover, it is not just in large and bureaucratized companies with grey owners that the capitalist culture has been eroded. Entrepreneurial talent outside these firms is also hesitant, or absent, and Western economies are increasingly short on new, entrepreneurial firms. For instance, the start-up rate of firms in the United States and Europe has been in decline for some time. The same is true for firm exit rates: a smaller share of firms go out of business today. As a consequence, the average age of firms has been going up, and older companies also employ a larger share of the workforce today than in the past. If we follow one metric, old firms hired 65 percent of the total U.S. workforce in 1987; in 2012, that figure stood at 80 percent. Moreover, less than 4 percent of younger households held shares in private companies in 2013, down from 11 percent 24 years earlier. Young people today are more pessimistic about starting companies and taking risks than older generations. People increasingly prefer employment, and to stay in a job once they are there, even if surveys show that a remarkably high and growing share of employed people are dissatisfied with their work and workplace.

The rising demand for planning and control is not only coming from within. External regulators demand their share of control over companies, too. And where internal and external demands come together, we find one of the most revealing characters of modern corporate managerialism—the compliance officer. Today the compliance officer represents one of the fastest growing occupations in corporate America, and—besides top management and the board—compliance is also one of the most powerful roles to have inside a company. Few top managers dare to do anything before receiving permission from compliance, and even fewer still dare to act against the will of a compliance officer. But the role of the compliance officer is to be exactly the opposite of an entrepreneur—to reduce uncertainty and experimentation, to inflate market risks and downplay market opportunities, or simply to say no. In essence, the chief task of the compliance officer is to eliminate one of the core elements of the entrepreneurial learning process—trial and error—because errors should not be allowed.

Corporate managerialism has been the handmaiden to grey owners, and has helped to steer capitalism in a direction that makes it dull and risk-averse. Together they have replaced the spirit of entrepreneurship and experimentation with a culture of predictability, certainty, and control. And, as a consequence, they have created a capitalist system that has reduced economic opportunity.

Severing the Link between Grey Capital and Ownership

Capitalism in America and Europe is approaching a crisis. Like most other economic crises, it is growing from the inside out—and it has not been forced upon us by others. It is always tempting for market economists like us to blame governments and regulators. It is also easy because it is obvious that regulations increasingly have hamstrung firms and made markets less competitive. But the crisis of capitalism now is far more about the transformation of ownership and the effects that this silent takeover of firms by institutions is having on corporate behavior and the economy at large. To work better, modern capitalism has to correct its ownership problem.

Capitalism’s ownership problem cannot be fixed unless grey capital and institutions are prevented from taking complete hold of corporate ownership. Grey capital already represents a significant share of corporate ownership, and no company of size, nor one aspiring to grow, can neglect its role. Given current demographic forecasts, institutions appear poised to continue their growth and take an even greater ownership role in Western capitalism. On current trends, institutions will squeeze out those capitalist owners that remain, and their portfolio approach to investment will make the problems of absent ownership even greater.

Reforms to sever the link between savings and institutions on the one hand and ownership on the other could aim at getting institutions to join with capitalist owners, even if such reforms would imply a loss of influence for grey capital. The situation has to be handled with care. Badly designed reforms can damage access to corporate funding or make firms seek even more debt rather than equity financing. Given how savings are organized now, companies could not do without institutions and the capital they intermediate, and reduced access to their resources can make capitalism lose a key input. Hence, clearing out asset managers cannot be the purpose of reforms. Actions have rather to be focused on differentiation between forms of ownership.

One way to achieve that is to allow companies greater freedom to discriminate between owners by expanding the usage of dual-class stock structures. Active ownership is prioritized by different rules for economic and voting rights. As ownership grows more concentrated in institutions, maintaining entrepreneurial leadership becomes increasingly challenging, and when entrepreneurial leadership is weak, company development slows down. A successful company builder like Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, for example, exercises ownership differentiation between A and B classes of shares. Both Google and Facebook have dual share structures, something that has arguably helped to maintain a culture of innovation in those firms. A few days after Facebook’s initial public offering, founder Mark Zuckerberg owned 18 percent of Facebook, but controlled 57 percent of the voting shares. The reason is obvious—maintaining entrepreneurial control.

Ownership differentiation is a red flag for many in corporate finance. Regulators do not like it and tend to support ownership democracy. In Europe, authorities have made efforts to remove ownership discrimination, and less than a decade ago there was a political campaign to rule out dual-class stocks entirely. The central argument has been that discriminative share structures suppress ownership, and in light of investor and ownership behavior from earlier decades, that argument has not been difficult to prove.

Yet the world is different now. Ownership has already become passive, and the primary challenge no longer arises from the old ownership paradigms or the corporatist cultures in companies that were previously run by founding families. It is true that, in the past, ownership competition was stifled, but the main threat to such competition now comes from institutions. Dual shares, rightly executed, can therefore help safeguard entrepreneurial capital and habits that are still present in companies, and thus help to defend and promote entrepreneurship more widely.

Another way to reform ownership structures is to prevent state-owned institutions, such as sovereign wealth funds, from investing in publicly listed companies, or at least investing in stocks that give them voting power. Most business observers agree that governments should generally not own companies. Few, however, appreciate the scale of corporate socialization that has taken place over the past few decades through government investment vehicles and state pension funds. In the past, capitalists feared that government owners would want to be active owners. But the main problem now is rather that governments are passive owners that chase yield just like every other money manager: equally fearful of risks, they demand rules and guidelines that destroy the culture of entrepreneurship and experimentation.

A third approach to severing the link between institutions and corporate ownership is to reform tax systems, especially with the intention of reducing the strong incentives to prefer debt financing. Current corporate tax regimes are rigged to favor debt financing. In most Western countries, large company owners are faced with a simple choice: if they borrow money, the interest is a deductible cost, whereas the returns on equity financing are not deductible. In other words, a company that prefers to get funding from real owners through equity faces a completely different metric of capital costs. The capital advantages of debt-financed companies, combined with the erosion of entrepreneurial corporate ownership, have diffused and confused corporate decision-making, chiefly by reducing the ownership role. Privileging debt financing only exacerbates the migration of influence away from equity owners to capital markets and bureaucratic credit committees.

If the influence of such institutions, distant in mind and matter from real entrepreneurship, is to be limited, the role of equity has to be promoted. After all, that is the active ingredient of capitalism. For capitalism to promote the culture of entrepreneurship and experimentation, ownership has to be in the hands of people with the power to be entrepreneurial and experimental. It is impossible to have a healthy capitalism without capitalists, and the way to fight the current anger against capitalism is to reinvigorate the original incentives of capitalist ownership.