Ever since the domino collapse of Communist regimes in the Soviet Bloc in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the world has been waiting for China to follow suit. Indeed, the fall of the Chinese Communist government would probably mean the real end of history given the size of the country. Yet nearly thirty years later, history hasn’t ended and the authoritarian government is still going strong. No one can be sure about how long the Chinese regime will last, but it shows no sign of collapsing anytime soon. China observers have changed their research topics from predicting when the country will democratize to understanding why it is resilient to democratization. Although many people haven’t given up their hope that China will one day become democratic, here I focus on why the Chinese political system has been working without liberal democracy, at least for the past thirty years. There are different ways to explain authoritarian resilience in China, such as elite power sharing,1 Confucian meritocracy,2 and institutional fragmentation.3 Here I shall focus on another important factor—public opinion and mass political support for the Chinese Communist government. Advances in public opinion research over the last three decades paint a strikingly different picture of Chinese political life, one that challenges fundamental Western preconceptions about democracy and casts recent Chinese political history in a new light.

The Rise of Public Opinion Survey Research in China

One of the most remarkable changes in the past thirty years in the study of Chinese politics is the rise of public opinion survey research. Before then, Chinese politics was sometimes described, with a mixture of images, as a Byzantine-style palace coup d’état behind the bamboo curtain. China scholars were trained to predict policy and personnel changes by reading the front-page articles of the Communist Party’s official newspaper, the People’s Daily, and detecting the slightest word changes. They were also trained to closely examine the official photos in which leaders appeared in different orders, symbolizing the subtle realignment and reconfiguration of elite power balance. Even today, elite politics remains a crucial component in the study of Chinese politics.4

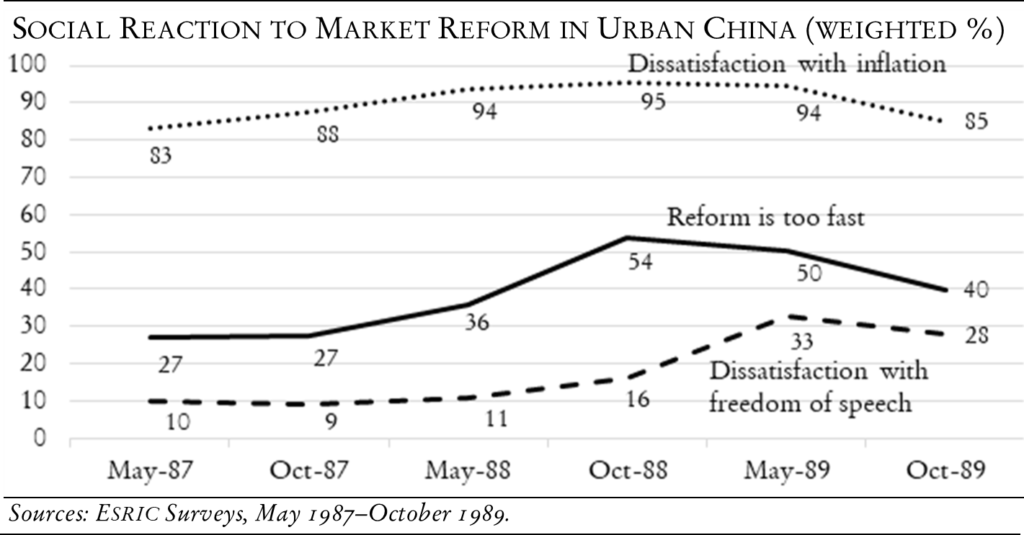

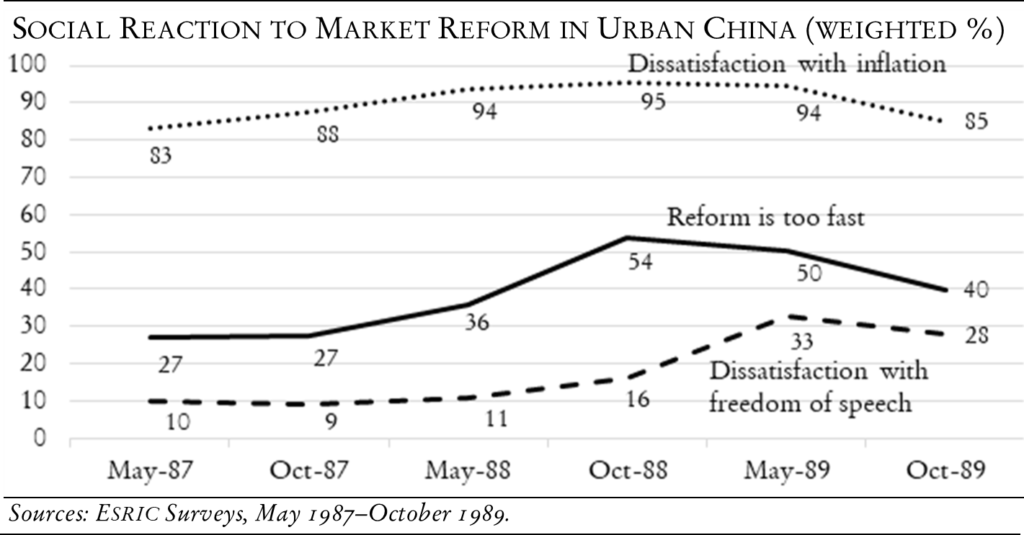

As China opened up, however, government officials and scholars realized the importance of collecting scientific data on public opinion. In May 1987, the Economic System Reform Institute of China (esric) conducted the first public opinion survey using a national probability sample based on China’s urban population. The esric was set up as a think tank by then prime minister Zhao Ziyang. Concerned about public intolerance and political instability, Zhao ordered esric to carry out biannual urban surveys to monitor the public mood during China’s transition from state planning to market capitalism.

The leader of the esric survey team was Yang Guansan, a scholar-official who was a brilliant economist and a graduate of the 1977 class, which was the first crop of China’s college graduates in the post-Mao era. Under his leadership, the esric conducted six urban surveys in May and October of 1987, 1988, and 1989. While analyzing the survey data, Yang observed rapidly rising public dissatisfaction with inflation, unemployment, social morale, and government inefficiency.

In early 1989, Yang wrote a top-secret internal report to Zhao Ziyang, showing the survey results and warning him of the danger of urban unrest. It was too late. The massive urban protests began in April that year. Zhao and the other leaders in the Chinese Communist Party never had the time and appropriate measures to respond to the public dissatisfaction. When the protests were suppressed and when Zhao Ziyang was stripped of all of his titles, Yang Guansan’s report was found on Zhao’s desk. An investigation followed and Yang Guansan was found guilty of instigating the urban riots. He was immediately arrested and jailed at Qin Cheng Prison, the place for the highest-level political prisoners such as the Gang of Four.

In 1991, Yang was released from Qin Cheng. He managed to conduct the esric surveys two more times in 1991 and 1992. The 1992 esric survey was particularly important because it adopted many questions from the General Social Survey in the United States, therefore making the Chinese data systematically comparable to other societies for the first time. As Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour in 1992 confirmed China’s determination to continue market capitalism without political liberalization, Yang finally decided to give up his political and academic career. He turned down my invitation to come to the United States as a visiting scholar and jumped into the futures market. Soon he became a successful trader and a frequent visitor of Beijing’s private clubs in his black Mercedes-Benz 600.

After a brief quiet period in the early 1990s, public opinion survey research regained its momentum in China. At the forefront of political science surveys was Shen Mingming. A Michigan-trained political scientist, Shen returned to Peking University and took over the leadership of the Research Center for Contemporary China (RCCC) in the mid-1990s. Since then, the RCCC worked with many international scholars and conducted numerous national and international surveys, such as the 1999 Chinese Urban Survey, the 2004 Legal Survey, the 2008 China Survey, the fourth, fifth, and sixth World Values Surveys, and the 2013–2015 Urban Surveys, among many other local and specialized surveys.

One of the most important contributions to public opinion survey research by the RCCC was its pioneering use of spatial sampling in China during the 2004 Legal Survey under the leadership of Shen Mingming and Pierre Landry.5 Traditional sampling methods relied on household registration records, which were often incomplete, inaccurate, and politically difficult. The GPS-based spatial sampling can avoid these problems and more easily capture any resident, particularly in large cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen where the migrant population can be as high as 30–50 percent. Since then, spatial sampling has become a standard technique that has assured the representativeness of survey samples in China. This sample representativeness later turned out to have important implications in the study of regime resilience.

Survey research has mushroomed quickly in China since the 1990s. There are several large-scale national surveys backed by generous grants from the Chinese government, such as the Chinese Labor Dynamics Survey (panel survey) conducted by Sun Yat-Sen University, the Chinese Family Panel Survey conducted by Peking University, the Chinese General Social Survey conducted by Ren-min University, and independent surveys conducted by overseas scholars, including the World Values Surveys in China, the Asian Barometer Surveys in China, the Chinese Income Inequality Surveys, and so on. In addition to using spatial sampling, these surveys also borrowed many questions from the existing international surveys. Today, survey research about China can rival any country in the world in terms of sampling technique, questionnaire design, and survey quality control; and there is lots of survey data available from China, much of which is underutilized.

The “Surprises” of Public Opinion Surveys

Public opinion surveys have had profound influence on the study of regime resilience in China. Sometimes these surveys challenge long-existing beliefs about political and social realities. Below I will mention five controversial and provocative findings in Chinese public opinion surveys.

(1) The Tiananmen protest was not a pro-democracy movement. While analyzing the esric data, I found something very interesting and unexpected. Public dissatisfaction with inflation, unemployment, social morale, and government inefficiency skyrocketed during the peak of the urban protests in spring 1989, but the majority of urban residents in October 1988 (54 percent) thought that market reform was going “too fast,” and such “anti-reform” attitudes closely echoed the rise of inflation during the same time. In the meantime, public demand for liberal democratic ideas such as freedom of speech and freedom of the press never surpassed 33 percent, even in May 1989.

Putting these findings together, what the esric surveys reveal is that the Tiananmen Square protest was by nature an anti-reform movement when urban residents panicked about the negative consequences of marketization. In a miracle of miracles, if there were free elections, the conservative anti-reform candidates probably would have won, and China would have returned to the centrally planned system where urban residents enjoyed a cradle-to-grave social safety net.

This paints a very different picture from the Western media’s coverage of the Tiananmen protest. According to the Western media, the Tiananmen protest was a pro-democratic movement where the majority of Chinese urban residents demanded liberal democratic reform. Discussing the findings of the esric surveys was very unpopular in the early 1990s, when Communist governments in the Soviet Bloc were collapsing.6 Yet the regime resilience in China later proved that the findings of the esric surveys were a realistic reflection of public sentiment in urban China. Today, the esric surveys stand out as the best and only available scientific evidence about what really happened in the spring of 1989 in Tiananmen Square. I would rather trust the results of the esric data, which are based on probability samples, than media reports based on anecdotal stories.

(2) Regime support is high. One of the most consistent findings in the Chinese public opinion surveys is the high level of regime support. Chinese survey respondents have shown strong positive feelings toward their government no matter how survey questions are worded, such as “support for the central government,” “trust in the Communist Party,” “trust in the central government leaders,” “confidence in the key political institutions,” “approval of China’s political system,” “satisfaction with central government performance,” or “identity with the Chinese nation.” Such strong regime support is found in different Chinese surveys conducted by different organizations and different investigators, including the World Values Surveys, the Asian Barometer Surveys, the Pew Surveys, the Chinese General Social Surveys, and the Chinese Urban Surveys, among others.

For example, in the fourth wave of the World Values Surveys conducted around 2000, when respondents in different countries were asked how much confidence they had in their country’s political institutions, China stood out by showing the highest levels of institutional trust among the selected countries, including both new and established democracies.

The most common challenge to the findings of strong regime support in China is the “political sensitivity” argument. According to this argument, China is an authoritarian police state and Chinese survey respondents hide their unhappiness with the regime due to fear of retribution. This view could be true of the Mao era, but it is a little out of date in today’s China. Analyzing online comments, researchers including Gary King, Jennifer Pan, and Molly Roberts found Chinese internet users were willing to be politically active and highly critical of the government, as long as they did not advocate organized political actions.8 Survey tools such as the list experiment have been used in the United States to detect, for example, when respondents hide racial biases.9 When the same list experiment was used in Chinese surveys, only 8–10 percent of the respondents were found to hide their unhappiness with the central government.10 Even after discounting for the political sensitivity effect, regime support in China is still among the highest in the world, higher than in many democracies.

Some people think that authoritarian regime trust is unhealthy and democratic regime distrust is healthy. This may be true, since critical democratic citizens can play the role of assuring government accountability. Yet it seems equally true that decision-making is more efficient and less wasteful of time and resources if there is less tension and greater harmony between the government and the public, particularly in societies with a lot of people and limited resources to spare.

(3) Interpersonal trust. The third “surprise” in the Chinese public opinion surveys is the high level of interpersonal trust. Many Chinese survey respondents in the past twenty years have consistently agreed that “most people can be trusted.” For example, 60 percent of the Chinese respondents in the sixth wave of the World Values Survey in 2012 agreed that most people could be trusted, ranking the second highest in the world only next to the Netherlands (62 percent) and much higher than many democracies such as the United States, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea, in which only some 30 percent of citizens expressed trust in each other. This finding is counterintuitive because it conflicts with the traditional theory of democracy, which tends to make interpersonal trust and social capital a precondition for the successful functioning of democracy.11

Such a finding is equally controversial. Some people do not want to believe it because it does not match their impressions when they travel to China and talk to Chinese people.12 Unfortunately, personal impressions cannot serve to discredit survey findings, especially when surveys are based on representative samples. The disbelievers need better evidence to challenge the survey findings.

Others tend to argue that interpersonal trust has different meanings in different societies. China is a Confucian society, so interpersonal trust must mean trusting one’s own family members, while in democratic societies interpersonal trust means trusting strangers. Such a depiction is only partially true. While family trust is very high in China, it is not the most important reason for the high level of general trust. Instead, community-based trust turned out to be most closely related to general trust in China, and it has a positive effect on regime support in multivariate regression analysis when other factors are controlled. The abundance of social capital despite the lack of democracy seems to make China a significant outlier in the existing theory of civic culture and democracy.

(4) Political activism. The fourth “surprise” in the Chinese public opinion surveys is the high level of political activism. For example, in the 2012 Chinese Labor Dynamics Survey, nearly half of employees mentioned that they had at least one labor dispute in the past two years. In the 2004 Legal Survey, only 6 percent of the respondents chose to do nothing when they were involved in legal disputes, and the rest would try to resolve them by various channels, including the court, the labor mediation bureau, the news media, the internet, petition, and protests.

These findings are consistent with the media reports of the increasing number of mass protests in recent years, particularly at the local level. For example, the New York Times reported that there were 180,000 mass incidents in 2010, compared to only 10,000 in 1994.13 The scale of these incidents ranges from a few protesters or petitioners to as many as 100,000. Challenging the government is no longer the business of a few dissidents and intellectuals.

Recent high-profile incidents have been widely reported by Western media: the protest against the local government’s handling of a young girl’s drowning in Wengan in 2008, protests against a chef’s death in Shishou in 2009, the land dispute in Wukan in 2011, the mining plant dispute in Shifang in 2012, the wastewater processing plant dispute in Qidong in 2012.14 These incidents have generated considerable excitement among Chinese dissidents and some Western media outlets, who tend to describe them as harbingers of political change, a stepping stone towards democracy, or the beginning of the collapse of the authoritarian regime.

On the surface, political activism seems to contradict regime support, as the former brings out public political contention against the regime in the conventional belief. Yet, what is remarkable is that in survey data such as the Chinese General Social Survey, trusting the central government makes people protest more.15 In other words, central government supporters and the protestors are the same people.

Authors such as Keven O’Brien and Li Lianjiang16 believe that Chinese citizens engage in a clever practice in which they protest against local governments and their bad policies while using the central government’s glorious propaganda about serving the people. According to this belief, the protestors learn to fight for their rights in this process, and eventually will fight against and ultimately bring down the authoritarian regime itself. In contrast, others such as Yanqi Tong and Shaohua Lei17 and Peter Lorentzen18 believe that mass protests at the local level are encouraged by the central government either through the CCP’s populist ideology of Mass Line, or to test and identify unpopular local policies and officials. Such a practice will eventually improve public support for the central government. If the second view is true, political activism is an integral component of regime resilience in China.

(5) Government responsiveness. The fifth “surprise” is the high level of government responsiveness. For example, in the second wave of the Asian Barometer Survey conducted in 2008, 78 percent of mainland Chinese respondents agreed that their government would respond to what people needed. In contrast, only 36 percent of Taiwanese respondents agreed with the same statement in the same survey. The percentages are even worse in other East Asian democracies that copied the Western liberal democratic system, including Japan (33 percent), the Philippines (33 percent), Mongolia (25 percent), and South Korea (21 perecnt).

In a multivariate regression analysis when other factors such as age, education, gender, income, religiosity, and geographic location are taken into consideration, government responsiveness played the single most significant role in promoting regime support in China.19 Existing studies typically attribute the high level of government support to three things: economic growth, media control, and cultural values. According to these studies, the Chinese are happy with their government because (1) their economic conditions have improved during China’s period of rapid growth; (2) they are brainwashed by the government-controlled media, which always presents a rosy picture of the country; and (3) the Confucian cultural values make people respect political hierarchy and avoid challenging authority.20 Yet when these three factors are compared with government responsiveness in the same regression model, the latter continues to show the strongest impact in promoting regime support.21

One of the most common challenges to the perceived high level of government responsiveness goes like this: the Chinese live in an unfree society so that they have extremely low expectations about what their government can do for them. They tend to be thrilled if their government does a little of something.22 In a democratic society, the government regularly responds to public demand, yet the public is always grumpy and constantly asks for more. But this view needs to present real evidence that democratic citizens hold higher expectations of their governments than authoritarian citizens. In fact, the high level of public political activism discussed above suggests that Chinese citizens may have high expectations, and that they do not hesitate to challenge their government when they perceive any mistreatment by its officials. Even if the view of low expectations is true, it discounts the importance of public opinion. Positive public opinion of government responsiveness at least demonstrates external political efficacy, a political commodity desired by any government, regardless of how much a government responds.

Another even more provocative explanation of the above finding is that the Chinese authoritarian government is actually more responsive to the public than a democratically elected government such as in Taiwan. Leaders of a democratic government may be hyper-responsive to public opinion only during the election season, and only to their own supporters, but less so once they get elected, between elections, and to those who do not vote for them. In contrast, leaders in authoritarian China do not have the luxury of electoral cycles. The CCP claims to represent the interests of the highest number of people in China, yet it does not have elections as a simple but effective yardstick to measure such representativeness. The CCP becomes paranoid and compelled to respond even when it sees a single protestor on the street. Researchers such as Tong and Lei in their 2014 study of protests in China23 show that the CCP spends a large amount of time and resources to calm and compensate protestors and petitioners, as an effort to maintain social stability.24 Perhaps that explains the perception that the CCP spends more on maintaining social stability than on defense.

Authoritarian Resilience and the Theory of Democracy

The information explosion based on public opinion surveys in China in the past thirty years has left a few cracks in the empirical foundation of some of the classic theories of political science that were first developed in the West with limited firsthand evidence. For example, the classic theory of civic culture was developed from survey data in only five countries—the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, and Mexico. Today, the World Values Surveys cover more than eighty countries in all continents with human inhabitation.

Among these countries, China stands out as an outlier and does not fit the theoretical predictions of Western political science. As discussed in the above mentioned “surprises”: (1) the Tiananmen protest in 1989 was an anti-reform movement, but it was expected to be a pro-democratic movement; (2) the Chinese regime enjoys strong public support even though many in the West expected it to have collapsed already; (3) social capital in China is among the highest in the world, despite political science’s expectation that its authoritarian political system would produce public distrust; (4) the authoritarian government is (perceived to be) highly responsive while the theory of democracy predicts otherwise; and (5) Chinese citizens are politically active and enjoy a strong feeling of political efficacy even if they are expected to be politically apathetic.

One problem in the existing political science literature is the rigid (and black-and-white) definition of democracy. For example, in the rankings of democracy and freedom by Polity25 and Freedom House,26 both highly respected organizations whose annual rankings are widely used in political science teaching and research, China has been consistently ranked at the very bottom in terms of freedom and democracy. Yet in the World Values Survey in 2012, more than 60 percent of Chinese respondents said they felt free, which was higher than in many democracies. Yes, the Chinese may have extremely low expectations, but they do feel free, and that feeling matters because unhappy citizens can cause political disruption.

The problem of measurement error is not only limited to China. In fact, when comparing the subjective feelings in public opinion surveys with the “objective” measures of democracy in the rankings assigned by Polity and Freedom House, public opinions throughout the world show a negative correlation with the democracy rankings. This negative relationship between the subjective and the “objective” measures of democracy can be clearly seen in the chart below, based on the Global Barometer Surveys (2010–2015) covering more than seventy countries and regions. The respondents in these surveys were asked about their opinions regarding the following six questions related to the levels of subjective democracy in their societies:

(1) The level of democracy is very high in my country;

(2) The democratic system in my country is functioning very well;

(3) Ordinary people in my country can freely express their opinions;

(4) I trust the media in my country;

(5) My government responds to what people need; and

(6) I am satisfied with my government’s performance.

These six items are combined into a single index of subjective democracy. When this index is compared to the Polity scores of “objective” democracy in these same countries and regions, the correlation coefficient is a statistically significant –0.51! In other words, democratic citizens feel less democracy and freedom in their societies than authoritarian citizens.

One way to solve the inconsistency between the subjective and “objective” measures is to slightly stretch the concepts in the political science literature. Concept stretching may carry a negative meaning because it may result in the diluted explanatory power of a theory. Yet overly rigid definitions can limit the scope and effectiveness of political analysis. Some of the key concepts in political science can be stretched (or enriched) by the available public opinion surveys. For example, the traditional study of authoritarian politics can include both elites and masses, and formal and informal politics;27 social capital can incorporate both civic trust (trusting strangers) and community-based interpersonal trust. More importantly, the traditional definitions of democracy, freedom, government responsiveness, and political legitimacy that are derived from institutional designs (objective measures) can be enriched by including public (not elite) perceptions of these concepts (subjective measures). Those who only focus on the institutional design of democracy but discount the importance of public perception of democracy run the risk of political arrogance.

Finally, a further barrier to understanding China’s authoritarian resilience is ideological bias. While people outside China take it for granted that academic research in China is ideologically limited, it is also true that China is frequently judged with ideologically tinted glasses by some media organizations and scholars in the West. According to these ideologically tinted views, the authoritarian political system in China is inherently bad; supporting such a system is unhealthy; civic trust is the only type that can qualify as interpersonal trust and social capital; government responsiveness is due to Chinese citizens’ “extremely low expectations,” and so on. These value judgements prevent researchers from understanding what is working and what is not working in the Chinese political system, regardless of whether it is good or bad.

This article originally appeared in American Affairs Volume II, Number 1 (Spring 2018): 101–17.

Notes

A shorter version of this article was presented at the Chinese Politics Workshop, Harvard University Asia Center, December 15, 2017.

1 Milan W. Svolik, The Politics of Authoritarian Rule (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

2 See Daniel A. Bell, “Reconciling Confucianism and Socialism?: Reviving Tradition in China,” Dissent 57, no. 1 (Winter 2010): 91–99; Doh Chull Shin, Confucianism and Democratization in East Asia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011); and Tianjian Shi, The Cultural Logic of Politics in Mainland China and Taiwan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

3 Melanie Manion, Information for Autocrats: Representation in Chinese Local Congresses (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

4 See, for example, Andrei Lungu, “Xi Jinping Has Quietly Chosen His Own Successor,” Foreign Policy, October 20, 2017.

5 Pierre F. Landry and Mingming Shen, “Reaching Migrants in Survey Research: The Use of the Global Positioning System to Reduce Coverage Bias in China,” Political Analysis 13, no. 1 (Winter 2005): 1–22.

6 Wenfang Tang and William L. Parish, “Social Reaction to Reform in Urban China,” Problems of Post-Communism 43, no. 6 (January 1996): 35–47; and Wenfang Tang and William L. Parish, Chinese Urban Life under Reform: The Changing Social Contract (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

7 The seventeen institutions included in the 2000 WVS are churches, armed forces, education system, the press, the labor union, the police, parliament, civil services, the social security system, television, the government, political parties, major companies, environmental protection organizations, women’s organizations, the health care system, and the justice system. The five key political institutions include parliament, the civil service, the legal system, the police, and the army. The average institutional trust score for each country divides the total trust score in seventeen institutions by the number of relevant questions asked (i.e., relevant institutions) in each country. See Qing Yang and Wenfang Tang, “Exploring the Sources of Institutional Trust in China: Culture, Mobilization, or Performance?,” Asian Politics and Policy 2, no. 3 (July–September 2010): 415–36.

8 Gary King, Jennifer Pan, and Margaret E. Roberts, “How Censorship in China Allows Government Criticism but Silences Collective Expression,” American Political Science Review 107, no. 2 (May 2013): 326–43.

9 David P. Redlawsk, Caroline J. Tolbert, and William Franko, “Voters, Emotions, and Race in 2008: Obama as the First Black President,” Political Research Quarterly 63, no. 4 (2010): 875–89.

10 Wenfang Tang, with Yang Zhang, “Political Trust: An Experimental Study,” chap. 8 in Wenfang Tang, Populist Authoritarianism: Chinese Political Culture and Regime Stability (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

11 As articulated by authors such as Gabriel A. Almond and Sidney Verba in The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963); Robert D. Putnam in Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993); Ronald Inglehart in “Trust, Well-Being and Democracy,” chap. 4 in Democracy and Trust, ed. Mark E. Warren (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999); and Francis Fukuyama in Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity (New York: Free Press, 1996).

12 Rory Truex, review of Populist Authoritarianism: Chinese Political Culture and Regime Sustainability, by Wenfang Tang, Perspectives on Politics 15, no. 2 (June 2017): 617–18.

13 See Andrew Jacobs, “Village Revolts over Inequities of Chinese Life,” New York Times, December 15, 2011; and Andrew Jacobs, “Harassment and Evictions Bedevil Even China’s Well-Off,” New York Times, October 28, 2011.

14 See Geoffrey A. Fowler and Juliet Ye, “Chinese Bloggers Score a Victory against the Government,” Wall Street Journal, July 7, 2008; “Chef’s Death Sparks Riots,” Radio Free Asia, July 22, 2009; Austin Ramzy, “Protests Return to Wukan, Chinese Village That Once Expelled Its Officials,” New York Times, June 20, 2016; Tania Branigan, “Anti-Pollution Protestors Halt Construction of Copper Plant in China,” Guardian, July 3, 2012; Jane Perlez, “Waste Project Is Abandoned Following Protests in China,” New York Times, July 29, 2012.

15 Tang, Populist Authoritarianism.

16 Kevin J. O’Brien and Lianjiang Li, Rightful Resistance in Rural China, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

17 Yanqi Tong and Shaohua Lei, Social Protest in Contemporary China, 2003–2010: Transitional Pains and Regime Legitimacy (New York: Routledge, 2014).

18 Peter L. Lorentzen, “Regularizing Rioting: Permitting Public Protest in an Authoritarian Regime,” Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 8, no. 2 (2013): 127–58.

19 Wenfang Tang, with Joseph (Yingnan) Zhou and Ray Ou Yang, “Political Trust in China and Taiwan,” chap. 5 in Tang, Populist Authoritarianism.

20 See Pippa Norris, Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Shi, Cultural Logic; and Shin, Confucianism.

21 Tang, with Zhou and Yang, “Political Trust in China and Taiwan.”

22 Truex.

23 Tong and Lei, Social Protest in Contemporary China.

24 Also see Zhu Yunhan, “Zhengquan Hefaxing Laiyuan yu Zhongguo Moshi Zhenglun” (working paper, 2016).

25 For the Polity Score, see Polity IV Individual Country Regime Trends, 1946-2013 (available at http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm).

26 For the country scores by Freedom House, see Freedom in the World 2017: Table of Country Scores, https://freedomhouse.org/report/fiw-2017-table-country-scores.

27 The best studies on the relationship between formal and informal politics can be found in Elizabeth J. Perry’s 2001 research on urban protest, “Challenging the Mandate of Heaven: Popular Protest in Modern China,” Critical Asian Studies 33, no. 2 (2001): 163–80; and in Lily Tsai’s work on the interaction between formal and informal institutions in rural public goods provision: see her Accountability without Democracy: Solidary Groups and Public Goods Provision in Rural China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), and “Solidary Groups, Informal Accountability, and Local Public Goods Provision in Rural China,” American Political Science Review 101, no. 2 (May 2007): 355–72. See also the study of informal personal ties embedded in the CCP’s formal organizations, by Victor Shih, Christopher Adolph, and Mingxing Liu, “Getting Ahead in the Communist Party: Explaining the Advancement of Central Committee Members in China,” American Political Science Review 106, no. 1 (February 2012): 166–87.

28 Subjective democracy index is a score based on factor analysis combining six questions related to the respondents’ feelings about the level of democracy, functioning of democracy, freedom of speech, media trust, government responsiveness, and satisfaction of government performance. The six items are highly correlated and therefore possible to be combined into a single index.